I spent most of my life trying to Americanize myself, but all that rebelliousness melted away when the earthquake hit

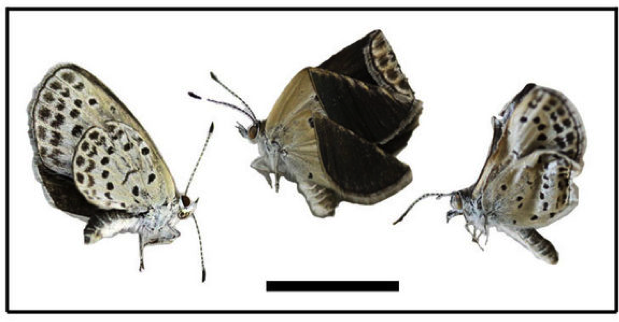

“Did you see?” my mother says to me, ripping up tissue paper. “The butterflies couldn’t get out of their cocoons. Their eyes are deformed, legs crooked, wings bent.”

She forwards me an article from Nature about the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear-plant explosions and the butterflies that had hatched from radiated cocoons. Zizeeria maha, they’re called, or the pale grass blue butterfly. This is a time when people in Tokyo are suddenly using foreign words like microsieverts and Geiger counters while avoiding nuclear and radiation, and instead talk about butterflies, whose collapsed eye sockets resemble popped bubble wrap. “If the soil is contaminated, everything is contaminated. If the water’s contaminated, everything’s contaminated.”

My mother loves concrete because it lets her high heels clack. She’s like an indoor cat that appreciates nature from the closed window. She’s always hated butterflies, calling them caterpillars with wings. And here she is, obsessing over them.

I say goodbye, click the exit box, and shut my laptop. The New York sirens wail outside my apartment, reminding me that I’m far away from her and have been for a long time.

***

One of the stories I love telling friends and new acquaintances is about working at McDonald’s in Tokyo when I was 15. I applied because I was bored and because I needed pocket change for going to karaoke with my friends. I wore pantyhose and heels for the first time and was handed a thick manual of small scripts, outlining possible responses to all kinds of situations with customers. If they asked for iced coffee, I would say, “May I offer you gum syrup or milk?” If they asked for chicken nuggets, I would say, “May I offer you one of our two signature dipping sauces, barbecue or mustard?” I was to bow before and after each encounter. I was to smile, and smile bigger when they asked for a “McSmile,” which was written into the menu at the price of zero yen.

Sometimes men would come up to the counter, already blushing, and ask, “So, Miss, how about a McSmile to go?” Since the manual didn’t take this kind of question into account, the short, balding manager had to pull me aside after the first time it happened and tell me exactly how I was to respond: “I’m sorry, sir, but the McSmiles are for here only.” And I was to smile like I was genuinely flattered and tell him gently to step to the side to wait for his meal. I got the McSmile order more than 10 times that summer. And I responded and smiled for them like a professional, counting down the minutes until I could meet up with my friends and scream into the microphone, attempting to sing all the lyrics perfectly just this once.

All summer I read from scripts, and it was comforting to not have to generate any original utterances for a while.

***

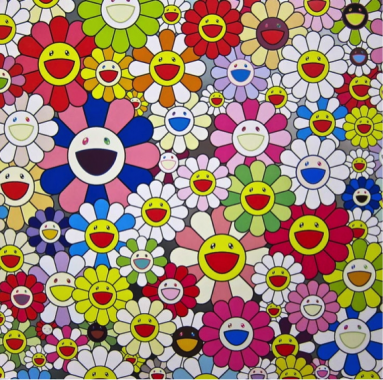

These smiling flowers make me nauseated, but I can’t stop looking at them. It’s not only that there are so many of the same faces. It’s not only that their eyes are glistening. It’s also that their mouths and the uniformity of their smiles all seem to be in on a joke that you will never get. They beam with insincerity (“Welcome!”) and lure the spectator in (“I have something special for you”), only to alienate and laugh (“Next please!”).

The flowers haunt me, not unlike the flowers in Alice in Wonderland that haunted my nightmares as a child. The iris turns to Alice and says, “Aha! Just as I suspected! She’s nothing but a common mobile vulgaris!”

Alice: “A common what?”

Iris: “To put it bluntly: a weed!”

The flowers shoo Alice away, and that’s when she encounters the hookah-smoking caterpillar, where she’s interrogated yet again on who and what she is.

Poor Alice.

The smiling flowers were painted in markers, created by Takashi Murakami, pop artist and founder of Kaikai Kiki Co. Eight months after 3/11, Kaikai Kiki held an art auction at Rockefeller Plaza to raise money for earthquake relief. One of the pieces was a painting by another contemporary Japanese artist, Yoshimoto Nara. It was titled “Patched Head,” and sold for $482,500.

Upon seeing it, I was overcome with a gentle gratitude for Nara’s wordless response to the tragedy; it was appropriate, graceful, timely. The girl, floating in the water, her look of confusion and irritation, the coned head, the patches attempting to provide immediate and temporary healing, the concussion stars, almost too perfectly captured my own response that day, the day I wasn’t there for.

***

March 11, 2011, fell on a Friday, and I woke up that morning at 9 a.m. I was getting ready to leave for JFK by 10 to catch my plane to Paris, where I had planned to spend the entirety of spring break, walking the cobbled roads of Montmartre and eating baguettes and cheese or whatever it was chic French people did. I wanted to meet new people at the youth hostels and take my mind off the midterm exams I’d just submitted. It was going to be a refreshing and satisfying break from life, college, and New York. I had bragged to people about this trip. It was going to be perfect.

Before shutting off my computer I opened my e-mail, and the subject headings stared back at me as though to say: There’s no way you’re leaving now. There were more than a dozen of them from friends, faculty members, and people I had never once received e-mails from: “Concerns about Japan.” “Checking in.” “Japan chaos.” “Is your family okay?”

Nothing from my parents.

Chaos?

I sat down again and did a quick web search borrowing key words from the emails. At this point almost 10 hours had passed since the 8.9 magnitude earthquake hit the northeastern coast, causing a tsunami 133 feet tall. These numbers didn’t make sense to me. I knew it was big but I didn’t know how bad this “big” meant.

My first thought: “My parents are fine. They’re in Tokyo.” I kept telling myself that if something had happened they would have contacted me many times by now. The buildings are made to resist even the biggest quakes. I thought back to all the drills they made us do in school, squatting under desks and pulling the seat cushions from the chairs to cover our heads in case lightbulbs fell from the ceiling. Everyone was always prepared, organized, safe. I had a plane to catch and baguettes to eat. Not going wouldn’t undo the chaos.

For the longest time I would think back to this urgency for personal leisure and hate myself for it. And I would tell people that Paris was awful and that I couldn’t enjoy anything given what had just happened, leaving out the baguettes, the museums, the carousels, the Louvre. I would leave out the part about signing into hostels with a fake name, pretending to be Korean American instead of the Japanese Korean that I was. In Paris I wasn’t Yurina Ko but Alice Wu, an alter ego I had used back in New York for websites and ordering coffee at Starbucks. It was a white lie that made me harder to track online and my name easier to pronounce.

One night I went out with two Armenian girls from the hostel who spoke some English, and we joined their Parisian friends who spoke only French. We bought cheap beers at a bodega and walked along the Seine, barely understanding anything we were saying to each other. I had them take a photo with a disposable camera, and they laughed and laughed. “Alice, say cheese!”

Poor Alice. A common mobile vulgaris in a bed of flowers.

The story I did tell people and repeat was the one about seeing the tsunami footage for the first time at Charles de Gaulle Airport on a little old TV screen. How I would never forget that first image of the houses and buildings floating in murky water and how I was able to pick up on the two French words that happened to exist in English: Catastrophe. Nuclear. How, immediately after absorbing the two words, I rushed to the youth hostel, where I was told that 15 minutes of Internet cost three euros.

When I opened up my account, I had finally received a message from my mother. The subject read: “Yuri!” But when I clicked it, all I saw were illegible symbols. My mother had written back in Japanese, and the hostel’s French computer couldn’t display the characters. There’s a word for this phenomenon in Japanese: moji bake, meaning garbled, or ghostly characters. I implored the young manager of the hostel to fix the settings, but he couldn't do anything, “Désolé, mademoiselle,” he said. “Désolé.”

Like an idiot I went to a fancy-looking restaurant and ordered a platter of escargot to cross off the first item on my list of things to try in Paris. And in that moment I found it fitting to swallow garlic-covered pests, the same slimy creatures I remember my mother killing in bulk in a tiny plastic bag filled with salt. They shrank and bled purple.

My curiosity about what she wrote to me and the futility of the whole computer situation drove me to binge-drink vodka with other travelers back at the hostel lounge and black out completely. The next morning, the same manager who couldn’t fix the language settings banged on my door and scolded me in thickly accented English for driving out two girls from my suite in the middle of the night. (Not the Armenian girls, some other ones.) He made the universal gesture for puking, and I refused to believe that I could possibly do that on someone, and especially on two girls.

I apologized and begged him to let me stay. A cleaning lady came in and started scrubbing the walls next to the bunk beds. In shame I spent the rest of the day sleeping under putrid sheets, half wondering whether my vomit had been green like the garlic sauce, or purple like my mother’s dead snails.

***

Zizeeria maha. Zizeeria maha. Zizeeria maha. In repetition anything could sound like a chant. A song meant to mesmerize, anesthetize, narcotize.

Immediately following the tsunami, Japanese networks collectively decided to cease airing commercials — all commercials. It would be disrespectful, the logic went, to try and sell anything in a time of grief and crisis. In its place they aired public service announcements.

The PSAs were made by the Advertising Council Japan, a private nonprofit organization. The most memorable and repetitive of the PSAs was disturbing in its innocence. Cartoon animals sang and danced about the importance of greeting our neighbors. The importance of saying “Thank you.” The importance of saying “Hello.” “Goodbye.” The song climaxed upward with the gibberish lyrics Po-po-po-pon!

Imagine that you watch the morning news. The afternoon soap opera. The evening variety show. Let’s say you’re the average citizen, exposed to television three hours a day or more. For every commercial that’s supposed to air, you’re given this cartoon nonsense instead, over and over again. Five, six times an hour. Maybe 30 times a day, for weeks.

Everyone in Tokyo was subjected to this, even if they didn’t own a TV. For Tokyo is a city where screens are placed on every surface of every establishment: inside trains and subways, cars, taxis, cafes, clinics, stores, on the sides of giant skyscrapers. There’s no escape from television in a city where television is both private and public.

Thank you. Hello. Goodbye. Po-po-po-pon! Thank you. Hello. Goodbye. Po-po-po-pon! Thank you. Hello. Goodbye. Po-po-po-pon!

Every one of them an adorable little cartoon creature. Every one of them smiling. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to suggest that the viewers were gradually hypnotized into a mass perpetual hysteria.

I looked for this PSA on YouTube after hearing my parents and other acquaintances from Tokyo complain about it. I wanted to bask in the same fatigue and hit the replay button as many times as possible to simulate the effect. There were even looped versions of the 30-second PSA that went on for an hour, and I sat there looking at the cartoons singing on my laptop instead of writing papers or doing whatever else I was supposed to be doing. I wanted to preserve the illusion that I was back home watching the same TV as my parents, and I found it easy and so comforting that the Internet allowed me to do that.

I soon became so addicted to this act of watching the PSA that I had no way of evaluating what response I had to begin with or which was the most authentic. The cartoon animals were always there on my screen, and there whenever I closed my eyes. And eventually, when their existence was just as ubiquitous to me as it was to everyone back home, I finally began to understand that the cartoons were there not to torture but to numb.

***

I went back to Tokyo in May 2011 to see my parents and recuperate from a grueling semester in university. Just as I’d expected, Tokyo was still dealing with the aftermath of what happened in Tohoku, and the quake was still the first thing people talked about. Not the tsunami itself or how much they were lamenting the great loss of people in the north, but the quake and the physical shaking they’d all felt in Tokyo — where they were, who they were with, how they reacted, how they knew from that moment onward that they would come out of it a different person.

I was there. It was the biggest quake I’ve ever felt in my entire life.

I was in a car and I felt the concrete rise up and down.

I was on a subway platform and an old lady thought she had vertigo, until we all told her we’d felt the shaking too.

I was at work and the elevators stopped working. We had to climb down 30 flights of stairs.

I was teaching and I had to calm my students down as they cried, confused about what was happening.

I was fucking and we left the hotel unable to get in touch with anyone over the phone.

I had to walk home because the trains and buses stopped.

I tried to buy dinner but the aisles at the supermarket were empty. I never wanted yogurt more badly.

I felt the aftershocks. So many of them.

I wished so badly that I had been there so that I could have a story. It was like being a virgin all over again and hearing from a dozen girls what an orgasm felt like.

I could have easily made something up, just like I made up a few of them just now. I imagined that the quake was colossal, but I had to compensate for all the Hollywood depictions of natural disasters that had been engrained in my mind, of skyscrapers falling and bridges splitting in half. I had just studied Barefoot Gen in my World War II seminar and couldn’t get rid of the image of melted faces and shards of glass stuck everywhere, like cacti needles. In my mind I had merged Hiroshima, Godzilla, The Day After Tomorrow, and crazy Grey’s Anatomy scenarios into one gory catastrophe in Tokyo. Even if I knew that none of these images in my head were remotely close to what the 3/11 quake felt like, I yearned for it to be the catastrophe I’d conjured up, just so that I, the humble quake virgin, could relate to it better.

I carried with me this awful desire to have been a victim. By missing out on the experience, I had become that outsider who might as well have been a foreigner. By missing out, I felt and intrinsically knew that my Japanese-ness had been reduced significantly, to simply someone who “used to live in Japan,” B.Q. Before the Quake.

I had spent most of my life trying to Americanize myself and to make sure I could build a career in New York so that I could be as far away from Japan as physically possible. All that rebelliousness melted away when the earthquake hit. Having been designated the outsider, I wanted in again.

***

After I came back from Paris I was bombarded with hugs from people I normally don’t see and looks of condolences from professors who didn’t know how to pronounce my name correctly, as though my parents were among the missing bodies. “Is your family okay?” “I’m so sorry about what happened.” “Did you know anyone?” “What a tragedy, it’s so awful.”

I couldn’t hide behind the mask of Alice Wu back on campus, so I responded with these statements from a mental script: “Yes, my parents are fine.” “Yes, thank you for saying that.” “No, I have no relatives or friends in the north.” “Yes, it was awful indeed.”

***

My mother hasn’t mentioned the butterflies since 2011. Instead we talk about her new terrier and my old cat. Every week when it’s Saturday night here and Sunday morning there, we stare into each other’s laptops and tell each other we’re doing fine. We compare the weather in Tokyo and New York. We say, “I miss you,” “I miss you too,” “I love you,” “I love you more,” and blow kisses to the tiny camera before clicking the exit button and staring at the inanimate screen again. Whenever I get an email from her, a part of me fears seeing the garbled characters again and learning about another national emergency. But this simple chatting routine every week has helped alleviate that fear, bring me back to the present — and the more repetitive the conversations, the better.

“It’s still cold here,” I’ll tell her tonight, same as last week.

“Same here,” she’ll say. “It’s still winter.”

“Same here.”