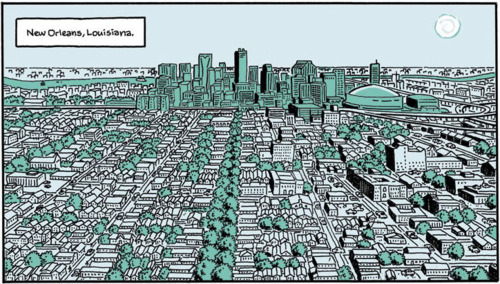

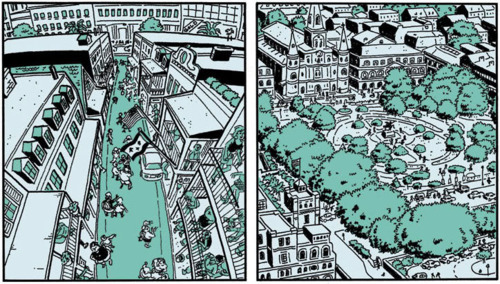

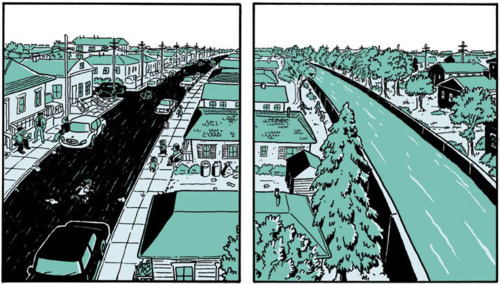

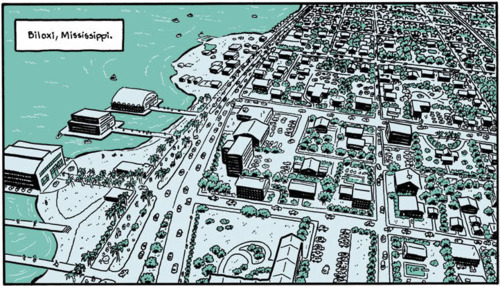

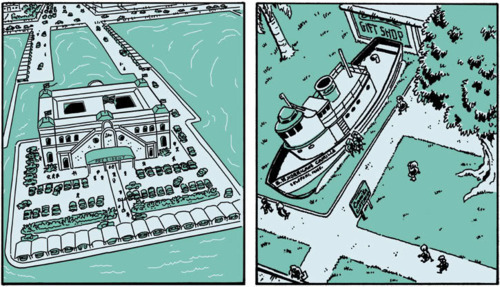

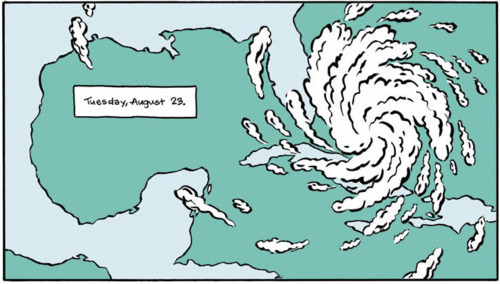

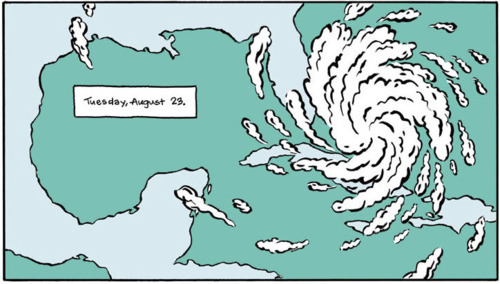

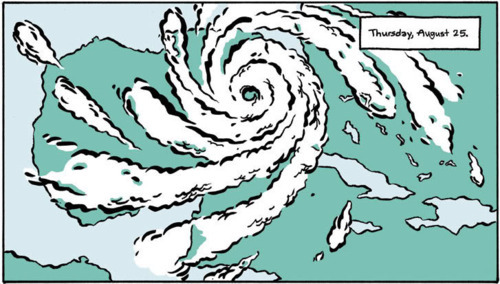

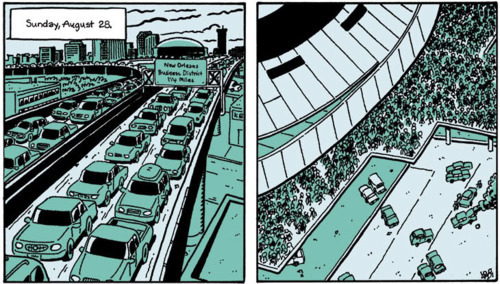

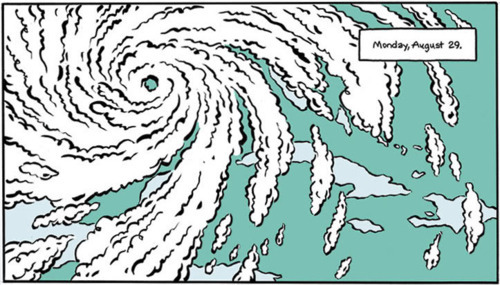

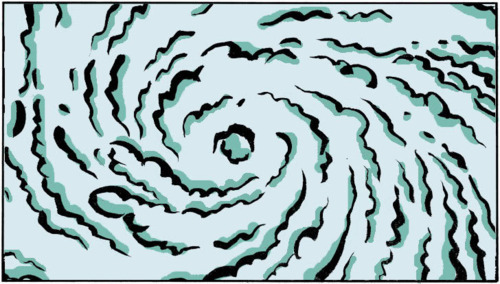

(Images from AD: New Orleans after the Deluge, Josh Neufeld, 2009)

NOLA’s Ongoing Disaster

By Alex Gecan

As I write this in late August, a plume of smoke from a 1,600-acre swamp fire is drifting over my New Orleans office and cars have begun to park on “neutral grounds” (grassy medians) in preparation for a growing storm off the Mississippi coast. Meanwhile, My parents’ street in central New Jersey recently became a semi-permanent detour for State Highway 27, which is underwater between the canal to the north (which also submerged the prep kitchen, walk-in coolers and wine cellar of a restaurant where I worked for a year) and the sloping grade of what becomes Highway 206. So if I seem emotionally compromised, it is because I am.

Today New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu offered a press conference, ostensibly to address the marsh fire. Instead he held forth on the gathering storm, offering the microphone to representatives from Entergy New Orleans, the New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board and the Army Corps of Engineers. Each said that his or her agency was “prepared for this storm.” But in the course of the conference, each encouraged us in turn to prepare for flooding, power outages, and the possibility of “a different conversation.” (Mayor Landrieu balks at using the E-word—evacuation.)

On its face, this sort of contradiction seems laughable, but it is a geographical inevitability—a series of inconveniences the metropolitan area has accepted in exchange for mild winters, proximity to ports, and other advantages.

But the real specter of disaster is that, should something go horribly wrong, we have no safety net. FEMA is broke. The city and state are broke. The mayor, who rode into office on a promise of change (as did his predecessor, Ray Nagin), has spent most of the Community Development Block Grant money on architectural restoration rather than economic development. He has decided to spend the $4.2 million donated by a Bloomberg charity to increase staffing in the city’s permitting department and “fund a study” on crime rates.

Meanwhile, many of the city’s worst neighborhoods, like the Upper Ninth Ward (not the Lower Ninth), built on top of an old landfill, remain unpatrolled. The cops we do have are facing unparalleled public backlash on account of the Danziger Bridge convictions and a spectrum of behavior at the top of the department that ranges from poor performance to alleged criminal activity. To say the least, trust in public servants is not at an all-time high.

And to make matters worse, the collective white knight of the city, the Office of Inspector General, has taken a wide departure from its original stance, diverging from dedicated funding (which put it decidedly outside of everyone’s pocket) to essentially courting federal contracts.

The office was officially opened in September 2007 with former Massachusetts Inspector General Robert Cerasoli at the helm. The office was assaulted from the get-go. The top-heavy executive branch submitted a budget proposal that excluded dedicating funding to Cerasoli. The city Attorney General balked at letting Cerasoli hire independent council. The city withheld materiel requisitioned by OIG (such as the computers for their first real office) and was obstinate when forced to cooperate with investigations. Nevertheless, OIG came to be.

Then three things happened. First, Cerasoli hired a former student of his, whose previous experience included only part-time work, to a top spot in the Ethics Review Board, the body that recruits and hires the IG. Then he began a feud with his deputy Leonard Odom. And then he got cancer and quit.

Despite the fragmentation within OIG, Odom met the ERB’s approval, but the requirements were too restrictive for Odom to take the top seat.

Enter Edouard Quatrevaux, a local boy who went to Vietnam, emerged as a brilliant military analyst, and spent decades investigating waste, fraud, and abuse in the Army and Department of Defense. He was the nexus of Cerasoli’s idealism and a local’s familiarity with “how it happens here.” And to put it bluntly, he began kicking ass. He stomped court officials for taking publicly owned cars home. He found over $9 million of city money that been misappropriated in 2010. He even stuck it to Mayor Landrieu for awarding a convict-tracking program to the Orleans Parish Sheriff despite lower bids that were on the table.

Then two things happened. FEMA (which is now out of money) gave New Orleans $1.8 billion to rebuild schools. Then the city signed a contract with Quatrevaux for $800,000 to monitor the assignment of that $1.8 billion for fraud.

This seems like a great idea, at least at first. Quatrevaux has been a whirlwind of transparency in a backward, Byzantine political environment. But here’s the rub: The money is going to Recovery School District projects, which are under the state’s jurisdiction. Unfortunately, the state doesn’t have a regulatory body capable of handling that sort of monitoring (which, in and of itself, is astounding given the political climate here), so they asked Quatrevaux to step in.

The real problem, however, is that he’s doing it on a city contract. Heretofore the funding for OIG came from a dedication of a certain percentage (0.75) of the city’s annual budget, mandated by the city charter, untouchable by the Mayor or the Council (in case the IG had to investigate them). Now, the man in charge of monitoring how the city does business is doing business with the city. Add to that the caveat that his purview only extends to investigating fraud and not waste, and the public starts to ask questions. To Quatrevaux’s credit, he has in one year exposed wasted monies that amounted to three times his budget for that year. His record has been excellent. But this paradigm shift is troubling at best.

But this also brings us back to the crux of the FEMA dilemma. Without going too far into the global climate shift debate (the why has no bearing on this issue, only the how), the recent uptick in calamitous weather means big trouble for little FEMA. Its coffers spent, the agency is ill-equipped to cope with flooding in the Northeast or whatever comes out of the current storm system in the Gulf. Should another school system be decimated by a large storm, earthquake, or fire (or anything else for that matter), there’s nothing left to build them back up.

The congressional scrum was quick to begin. Eric Cantor is quick to mollify the public with reassurances that the feds will find funds for disaster relief, but only by cutting spending elsewhere. This creates a novel hostage-squared situation—hostages of nature are held hostage a second time by partisan politicians. Ron Paul wants FEMA’s role to be taken on by private insurance companies, who already play policy ping-pong with people’s homes, claiming flood damage is actually uncovered wind damage or vice versa. And that doesn’t even get into the fact that we can’t enter into a discussion about privatizing emergency relief right now because we’re dealing with the aftermath of a hurricane and an earthquake in one region and are faced with a wildfire and possible tropical storm in another, and that destruction is not going to wait on the convenience of a national debate that barely exists.

FEMA’s record in recent years has been atrocious. The DHS IG (Department of Homeland Security Inspector General) has said as much. But a public agency has the benefit of transparent spending and the restrictions (however inadequate) of the Federal Acquisition Requirements. No matter how poorly it is run, it is not a company founded on the principle of profiting off of people hedging their bets against disaster.

And so we are left with a disaster-relief system that has been compromised by compromise. On a national scale, Congress is playing political tug-of-war with money that doesn’t exist or can’t be re-appropriated. Down in my neck of the woods, the Mayor who campaigned on a promise to change whatever it was the last guy changed is instead using federal money to preserve the way things were. The state is so backward it’s looking to a city official to oversee the disbursement of $1.8 billion from an agency that can’t afford it under a contract that subverts that official’s position.

With this marsh fire, as with many natural disasters in the past, the city waited too long to do too little. What began as a small conflagration ballooned into an inferno that was only contained by natural water barriers. Although speculation is now pointless as to whether or not early water dumps could have cut the fire short and prevented the hundreds of resulting hospitalizations (fortunately, all respiratory complaints), the city went along with national best practices and decided to let the fire burn out. At least, they did until five days in, when the fire had grown to its zenith, and they decided to start running aerial dumps, despite having said earlier that they would be useless, and ultimately rain and depletion of fuel would kill the blaze.

But they felt a compromise was necessary. They bowed to the disapproval of a public that felt ignored and took measures that they themselves knew to be fruitless. (They did extinguish a much smaller, secondary fire that abutted a state highway, however.) The dumps reek of currying political favor at the expense of public resources at a time when the latter is running miserably thin.

New Orleans, like the country, has—and is—compromised.

Alex Gecan is a freelance writer and web editor for New Orleans Magazine and MyNewOrleans.com. You can reach him at [email protected].

Josh Neufeld is a cartoonist & illustrator and the creator of A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge, a nonfiction graphic novel about seven real-life New Orleanians and their encounters with Hurricane Katrina. A.D. started as a webcomic on SMITH Magazine, and was released in an expanded hardcover edition in 2009 by Pantheon.