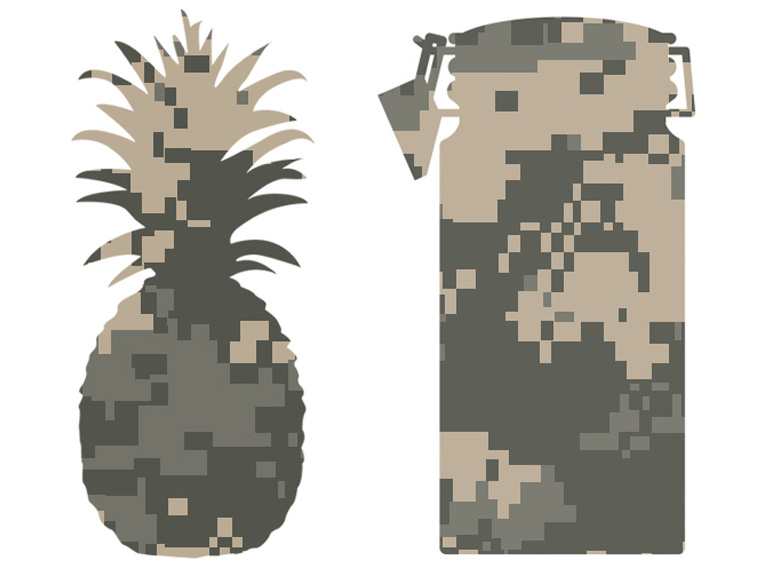

Since World War II, the aims of grocery shoppers, parents and the U.S. military’s Quartermaster Corps have merged

THE story, which varies a bit with the telling, goes something like this: around the time of the Napoleonic War, the French government offered an award of 12,000 francs for any method that cheaply preserved large quantities of food for transport to the front, however distant it may lie. The prize was given in 1809 to confectioner Nicolas Appert, who discovered that food cooked in a sealed jar wouldn’t spoil. Though he didn’t understand how it worked, canning was born.

Over subsequent decades canning increased in safety, affordability, and familiarity, and its military origin has since fallen into obscurity. While not all military food preservation techniques have garnered such renown, several others that have become an integral part of civilian life serve as the subject of food writer Anastacia Marx de Salcedo’s new book, Combat-Ready Kitchen.

Despite her devotion to preparing healthy, homemade meals for children, De Salcedo’s project began with the realization that she was sending her children to school with lunchboxes full of heavily processed food, wrapped in environmentally destructive packaging, and profiting food industry conglomerates. But, she declares, “it’s far worse than that…It was designed for soldiers.” The shock of this discovery prompted her to follow the origins of her children’s packed lunch back to the U.S. military’s research station in Natick, Mass., and Combat-Ready Kitchen is the record of her findings. Somehow, since World War II, the respective aims of grocery shoppers, parents, and the Quartermaster Corps of the U.S. military have merged.

De Salcedo concentrates on the money moving between the research center in Natick and its partner conglomerates. Together they have improved on the rations of old—pork and rice, frankfurters and beans—to develop bread that won’t go stale for weeks, guacamole that never turns brown, and energy bars that can be eaten on the run. These advances in both preservation and nutrition afford the military more options for feeding troops; with a greater range of foods that can be easily preserved, the military has more leeway for prioritizing taste and variety.

The partnership is a boon to both the military and the food industry. Even as recently as 2011 the U.S. military purchased some $3.8 billion of groceries in a single year. On top of that, military research spending on food—at a scale of eighteen Cooperative Research and Development Agreements in fiscal year 2007 alone—enables companies to develop processing and packaging technologies that give them an edge over their competitors. And for the military, producing these foods on a mass scale in peacetime shortens the amount of time necessary to mobilize supplies in the case of troop escalation.

Of course, a competitive edge is only worthwhile if there is a ready market for the product. Fortunately for the processed food industry, convenience is a shared concern of the armed forces and civilians alike; a preference for foods that are quick and easy to prepare, and that enjoy a long shelf life, is common both to the military and many American households. Even if most Americans don’t live under the same physical and mental duress as soldiers, they still want to eat healthily, and the military has mastered the art of producing food that is nutritious and has high acceptance across a broad swathe of people.

The convergence of consumer preference and processing technologies has also benefited the military. If soldiers on deployment eat the same fortified foods they enjoy at home, they consequently absorb the appropriate nutrition, maximizing their physical and cognitive abilities. The military spends huge sums of money on the development of foods that soldiers will want to eat, and incidentally, ordinary grocery shoppers want to eat them too.

If the energy bar is any indication, military and civilian values have converged at a level the Quartermaster Corps couldn’t even dream of. In partnership with Milton Hershey and his nascent chocolate company, the military developed what came to be known as the Logan Bar, or D ration, in the 1930s and ’40s. Packed with protein, carbohydrates, and caffeine, Logan Bars were made intentionally unpalatable, lest soldiers eat them too soon. In the following decades they slowly morphed into the First Strike Bars and Ranger Bars still in use today, as well as the PowerBars, Clif bars, LUNA bars, NutriGrain bars, and many other competitor bars lining supermarket and convenience-store shelves of the civilian world. Nutritionally and calorically dense, light, and portable, energy bars have come to be just as popular in school cafeterias as they are on the battlefield.

The convergence of military and consumer food preferences is as much a conceptual change as a historical one, marking a movement away from cooking as a pleasure or art to, as De Salcedo argues, a science—that is, a product of facts rather than experiences. Yet this conception is perhaps incomplete, or at least not entirely accurate. Food preparation has become oriented to achieving practical goals like nutritional balance, taste, and portability; and the quality of the food is judged according to quantifiable criteria rather than its creativity or innovation.

De Salcedo presents a world in which food isn’t cooked but instead is engineered according to predefined specifications. This may seem obvious, but it’s radical nonetheless. Historically, meals acted as displays of artistry and power. Royal or aristocratic chefs sculpted lavish spreads of difficult-to-find ingredients that reflected the status of their employers. The poor, meanwhile, ate whatever was on hand. Creativity allowed it to be as delicious as possible, but they had no knowledge of nutrition, and even if they had, it likely wouldn’t have changed what was available.

Engineering food to meet military objectives certainly makes a certain sense. What’s alarming is that these objectives have come to be shared by the average grocery shopper. De Salcedo, however, never takes her sense of alarm quite so far. Toward the end of the book she visits her local grocery store and fills her cart with the items bearing a military fingerprint. The moral of her story is blunt: Military technology dominates the supermarket. But while it’s clear she thinks this ubiquity bad, she doesn’t spend much energy explaining why. In fact, the only complaints she can muster are that the long-term health consequences of processed food haven’t been tested, and that it’s time for an overhaul of the FDA. Despite the pages and pages spent scrupulously detailing certain enzymatic processes and nutritional experiments, she never considers the more profound and interesting question of why eating has become so goal-oriented in the first place.

History shows that you don’t have to be a meticulous, ends-focused eater to achieve a balanced and healthy diet. As the Mediterranean diet clearly demonstrates, many traditional diets have provided people with the nutrition they need. Italians had been pairing tomatoes with olive oil for hundreds of years before anyone realized that the fat in the oil aids metabolism of the lycopene in the tomatoes. At the same time, it’s important not to discount the benefits of modern practices like food fortification, which has spared countless individuals from the ravages of malnutrition and made maintaining a balanced diet less of a conscious concern.

Military-inspired, efficiency-oriented eating has reached its apotheosis in the meal-substitute Soylent. Invented by a civilian for civilians, Soylent is a powdered drink that nominally contains all of the micro- and macronutrients a person needs in a day. It aims to be a complete replacement for meals and “normal” food, allowing consumers to save time on shopping, cooking, eating, and cleaning up, and spend their leisure as they please, instead of wasting it away on obsolete rituals. Efficient to an extreme, it’s still too soon to understand the long-term health impact of the drink, though De Salcedo would insist that you could say the same for many of the military’s inventions.

Health considerations aside, making convenience our sole dietary concern threatens our ability to place ourselves in the world. Food produces and is produced by the cultures we identify with, and while perhaps someday Soylent will be an indicator of a culture of its own, for now it still takes us out of the ones we belong to. Sharing recipes, cooking meals with family, meeting friends at a favorite restaurant—all these activities connect us to histories and cultures that may not be terribly efficient but are certainly worth preserving. If we step out of those histories for the sake of convenience (with Soylent) or realize they are not what we thought they were (because the military actually made that food), for better or worse we lose that connection.

As it turns out, the military is looking at adding Soylent as a combat ration. Yet it never intended to exalt convenience over all other culinary concerns. Though earlier research may have focused on portability, readiness, and nutrition, more recent efforts focus on how to better represent American food culture on the battlefield and, in the past two decades, how to make combat eating more like eating at home.

Maybe military food research isn’t all bad then. Many women, to whom the work of food preparation has traditionally fallen, have gained more free time and saved themselves tons of effort, thanks to ready-made and shelf-stable foods. A bagged loaf of bread at the supermarket that lasts a week or two may not seem like a significant time saver these days, but it does when you consider the time saved not only from baking but also from daily trips to a bakery to buy fresh loaves. Add to this the plastic wrap that keeps food fresh longer; salad that comes shredded, washed, and bagged; frozen breakfast pastries; and every other canned, jarred, and boxed food on the supermarket shelves and suddenly that’s a lot of food preparation time saved.

As strange as it may sound that military technology has eased possibilities for women working outside the home; De Salcedo herself testifies to it. Before she began the book she felt that “an involved parent, a mother who cares about what her children eat, makes their lunches herself.” Yet after three years of research and writing, she became a woman who unapologetically declares cooking “a dying art.” She describes watching her mother-in-law butcher a chicken, freezing the excess parts to use another time, and appreciating how much time she could save just buying packaged drumsticks and chicken breasts instead. Sandwich bread and salad greens that can sit around without going bad both reduce food waste and the frequency of shopping trips. But unbridled efficiency comes with its own mix of risks and sacrifices.

The choice between easily prepared nutritious food and artful cuisine is certainly much hazier and nuanced than it is clear-cut. Though concern about the military’s influence on our every meal may be well justified, we would be naive to think this influence is entirely pernicious. Nevertheless, it bears asking why certain qualities of food are privileged over others. Civilian life may not yet be entirely steeped in military values, but it has taken on something of their flavor.