With social media, the compelling opportunities for self-expression outstrip the supply of things we have to confidently say about ourselves. The demand for self-expression overwhelms what we might dredge up from “inside.” So the “self” being expressed has to be posited elsewhere: We start to borrow from the network, from imagined future selves, from the media in which we can now constitute ourselves.

This doesn’t guarantee “personal growth” however. The more we express ourselves for self-definition, the more we limit the self to what we have the means to circulate. The sort of self we can imagine ourselves to be becomes contingent on the available media.

Social media offer a wealth of new resources (images, links, likes, screen grabs, image macros, serial selfies, emoji, etc.) to continue to bait us into “becoming ourselves.” These seem to let us express the self without the limits of language, or the fixed centrality of the speaking subject. The self expressed through a suite of social-media accounts seems to pour into networked space from all over the place, spilling over the edges of unitary profiles and giving users the freedom to renege on a precomposed identity in favor of ongoing glimpses at the process of self-composition.

The push toward a self-concept of perpetual becoming would seem to thwart subjectivation as social control. But the more we construct identity through the means of social media, the more we self-assimilate to the incentive built into them: to turn all experience into more and more strategic expression.

How damaging is this? Users generally behave as though social media are safe spaces to reveal the self as an imperfect work in progress, but these media typically compile a permanent archive of our “becoming,” which negates its provisional nature. As much as the self feels uncontainable, yet it is contained.

It becomes the user’s problem to manage the tension between the static profile and the real-time experience of being a self in dynamic social-media feeds. How do users balance the freewheeling pursuit of immediacy, attention and salience within the network with the threat that it will all go on their permanent record?

The tension between the archive and the feed puts pressure on “authenticity,” which lingers on as a compass for the self. If one believes a unique “true self” exists, then the archive is always inauthenticating it, exposing contradictions, disproving its spontaneity, and undermining its supposed originality.

Active social media use urges a de facto rejection of the “true self” that users may not be ready to accept ideologically. It calls for a self that is reconstituted (for others and for oneself) the same way a recommendation page or a news feed is reconstituted in real time.

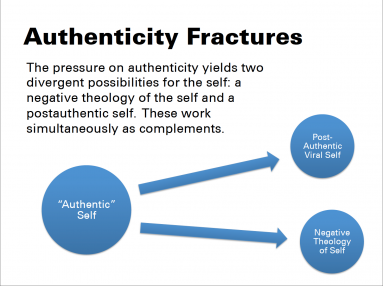

This pressure fractures authenticity into two divergent sorts of “self”: a self anchored in a “negative theology,” and a postauthentic self. These work simultaneously as complements.

The possibility that everything we do on networks is surveilled has generated an urge to remove the “true self” from charted territory.

In an essay for Rhizome about Google Glass, artist Molly Crabapple argued that “the things we once called souls are not legible to algorithms […] The network alters you in ways that make you more legible to the network. But maybe there are some things it still can’t get.”

As we make ourselves, or are made, more legible to the network, we may become more aware of what isn’t translatable to its formats. Deeper engagement with the network could provide a more thorough awareness of our “soul.”

In “Returning the Dream,” Adam Phillips quotes psychologist D.W. Winnicott: “At the center of each person is an incommunicado element, and this is sacred and most worthy of preservation.” Phillips interprets this as a “negative theology of the self” and argues that in Winnicott, “the aim of intimacy is to sponsor the solitary unknowability of the True Self.”

If that’s so, then social media would seem to destroy intimacy, replacing it with sharing and copious self-expression. But there is no reason to equate what is shared in social media with what is “authentic” about the self. Social media can support Winnicott’s negative theology of self by allowing us to express precisely what is inessential about ourselves, establishing the negative space where the ineffable self can reside.

Sharing is thereby a process of shedding, a way to purge what we think we know about ourselves but which is inherently wrong because expressible. Our “true self” is then constituted in the silences. The network, in this sense, actually alters us to have a soul, preparing the ground for it. And intimacy, then, is going over someone’s social media offerings and reassuring them that none of it seems much like them at all. The death of intimacy is when someone looks at your Facebook and thinks you’ve got yourself pegged.

But if our “deepest self” is inexpressible by definition, it is nonsensical to make “expressing the true self” into a life goal. Personal or artistic expression cannot then be about “sincerity” or “authenticity.” Yet few would accept that what they express through social media is inauthentic or false. What is going on there?

What’s going on there is the postauthentic self. The uselessly inexpressible “true self” would doom us to an unbridgeable isolation despite social media’s ubiquitous connectivity. It requires the postauthentic self as functional complement.

The postauthentic self is premised on the possibility that one’s traces — the ephemera of everyday life that is being ejected from the “negative theology” self — can be processed into a makeshift identity on social media platforms, through feedback and algorithmic processing. This identity can be shared and consumed not only by others but by oneself. You can enjoy yourself as a novelty item rather than confront oneself as a problem to solve, or a set of inborn constraints. The “What Would I Say on Facebook” meme was a small example of this, of how self-expression can be supplanted by self-consumption.

Postauthenticity (you might call it “normcore”) rationalizes the terror of ubiquitous surveillance and makes accelerated consumption benevolent. Doing more online causes not more anxiety about whether what you’re doing is “right” but instead fuels the algorithms’ generating a new version of yourself to consume. The burden of uniqueness is on the algorithm, not us.

Being on social media deepens awareness of what can’t be shared, protecting the exclusionary purity of the inexpressible within us, beyond public appropriation. Meanwhile metrics and algorithms stand in as a quasi-populist proxy for the postauthentic self’s approving other in the circuit of self-production.

From brand to meme

Postauthenticity rejects specific consumerist signifers of the self (their increased circulation in social media makes their meaning unreliable anyway) in favor of the “engagement” metrics that track content, which become the newly reliable basis for the self. With the self grounded in metrics rather than specifics, one positions oneself in the social-media environment less as a personal brand than as a meme. One adopts a “viral self,” anchored in continual demonstrations of its reach, based on ingenious appropriation and aggregation of existing content, not in its fidelity to a static inner truth or set of tastes. It is defined by its ability to circulate, not by the content of what it circulates.

To make the self-as-meme register, it’s imperative to associate oneself with dynamic, emotionally resonant things that circulate virally. When you like a brand, for instance, nothing really happens. Since the viral self is a self constructed to exist in feeds, it requires material that is not inert. By sharing viral content, the self is in play. We don’t circulate memes so much as the memes circulate us.

Virality serves an equally tautological token of authenticity, as the spontaneous yet inexpressible self is for the negative-theology self. It indicates the presence of "real" feeling.

Vicarious identification with metrics

Content recedes to mere alibi for engaging emotionally with the circulation data, leading to vicarious identification with how information travels rather than what that information encodes.

We shift from consumerist pleasures of fantasizing about how owning certain branded goods would make us into a certain kind of person and secure us a certain sort of affirmation to fantasizing about triumphant moments of social quantification, about getting likes and retweets, having lots of Tumblr activity, etc.

Virality becomes the horizon beneath which occurrences no longer figure socially, no longer count for anchoring identity or asserting a self.

Without viral content, you are in danger of becoming a blank.

A look at the most notorious supplier of viral content, Upworthy, may shed some further light on how to adopt virality as a technique of the self and engineer it as an end in itself.

No content (or self) is inherently viral; likewise, no content is inherently nonviral. Optimization techniques can always be applied. Upworthy's putative goal is to get its preferred content past filters and into massive circulation, but their tricks end up trumping the content, so the techniques to circulate the material are more revealing than the “things that matter” that they are about. Circulation itself becomes the content.

Most notorious of these techniques is the much-parodied curiosity gap headline: “You Won’t Believe etc.” But as employees explain in a recent New York magazine profile of the company, the specific formula is not the key and could easily change. What matters are what approached get results, as revealed in A/B tests of competing headlines. Hence the “real version” of any story’s packaging derives from the circulation process, with rejected versions doing nothing to compromise the winning one. Upworthy’s success in social media feed suggests we can approach identity in the same way.

Just as genuineness has proved irrelevant to content’s potential virality (stories are sometimes debunked after going viral), it is also irrelevant to the viral self, whose “authenticity” is an after-effect of having marshaled an audience. “Realness” is a matter of attention metrics rather than the fidelity of the content to some core “truth.”

Typical Upworthy material does not privilege uniqueness or complex emotional responses. Such subtleties belong to the negative-theology-of-self world of being so unique, you cannot be expressed comprehensibly. Rather, Upworthy emphasizes the use of formulas because they are comforting and uncool, and repel cynics who are more invested in exclusion than inclusion. They say they try to “reach people where they’re at”: “You don’t want to be that guy in your Facebook feed going, ‘These ReTHUGlicans out there …’ ”

That may be good advice in itself, but more significant, I think, is the assumption about who “you” are: a guy in a Facebook feed. Upworthy content strives to let you become that guy and not get filtered out yourself from the site of viral selfhood.

Upworthy’s intensive use of formulas illustrates how virality becomes a formal genre, recognizable independent of its circulation data. This helps permit one to experience virality as a feeling and identify with it in the face of inevitably disappointing actual metrics.

By encoding audience enthusiasm at the level of form, viral content permits vicarious participation not only in the viral story — whose apparent popularity helps encourage an indulgent suspension of disbelief—but in the social itself, conceived as a flow of information in social networks. The function of a story in social relations is shifted: it is not retold in time and dependent on co-presence, but instead linked to in space and "told" — that is, the identity quotient harvested — through circulating in networks.

If virality is the model, then social-media participation ultimately has no “content.” It is just a matter of exchanging and tallying gestures of sharing. As virality supplants authenticity, the emotion that viral content provokes, a feeling of spreading connection, threatens to become the root of “authentic” feeling. Having other sorts of feelings becomes pointless if you can’t be seen having them. We will want to feel only what will spread.

For instance, because I know my reactions reading can be performed on Twitter, I am sure to have a reaction—to method-act my response and see how it goes over. That is an added incentive for emotionality that I don’t get from perusing People in a grocery-store line.

The ubiquity of virality makes it seem as though one can fit in only by spreading oneself indiscriminately. Social media sustain a measurement system that makes “more attention” seem always appropriate and anything less insufficient. If your appropriated content is not circulating ever more widely, then you are disappearing. This can feel like total exclusion: You are adding nothing to the social bottom line. You are not inspiring anybody. But it is also a confirmation of the other sort of “authentic” self that must disappear to actually exist.