Tracts conceived by crusaders seeking to eradicate the foreskin were published by pornographers seeking to avoid censors.

For several years now, I have been collecting a strange series of books put out by two mostly forgotten publishers, Panurge Press and Falstaff Press. Both operated in the first half of the 20th century, flourishing in the late 1920s and 1930s, and both focused on so-called “gentleman’s” titles: unexpurgated literature, curiosa, and pornography. More than bizarre curios, they’ve drawn me in because of the way they illuminate a strange moment in the history of American censorship that had vast consequences for almost all the dicks in America. The presses themselves emerged from a quirk of American obscenity laws, which left a strange lacuna that allowed them to operate.

One of the books, published anonymously in 1931, tells the story of surgeon who treated a man with “a very long but thin and narrow prepuce that had always been an annoyance to him.” The man, after witnessing the benefits of circumcision for his two children, “arranged to do it all by himself, and give the family and the surgeon a sample of his courage and a simultaneous surprise party.” The surgeon recounts what he saw:

When I at length arrived at the scene of carnage, I was directed to the wood-shed, on the outskirts of which hovered the family, frantic with fear and apprehension; within, in the darkest corner, with wildly dilated eyes, and performing a fantastic pas seul, was a man with a huge pair of scissors dangling between his legs, warning all persons as they valued his life not to approach or lay a hand on him. He had shut the scissors down so that it clinched the thin prepuce, and there his courage and determination had forsaken him. He lost his presence of mind, and was not even able to remove the scissors. He had simply given one wild, blood-curdling yell—like the last winding notes from Roland’s horn at Roncevalles—that had brought his family to the wood-shed door, and they had sent for me.

Though violent, this passage doesn’t depart too far from the hallmarks of the genre. Asking why a book like this would be distributed with pornography, even as a disguise, points the inquirer to the governing irony of gentlemen’s titles: The restrictions on publishing sexual material often activated the erotic content of otherwise innocuous or boner-killing stories. Their fate becomes even more juicy when the role of this censor-evading smut in promoting circumcision as an anti-masturbation cure comes to light.

The 1873 Comstock Act prohibited obscene material, contraceptives (including “rubber goods”), or information on abortion to be sent through the United States Post Office. But while so-called smut hounds, including the law’s namesake, Anthony Comstock, worked tirelessly to seize and destroy material deemed pornographic and obscene, there was a loophole. Sexually explicit material was left available to a select clientele of professionals: doctors and other medical professionals, clergy, lawyers, sociologists and anthropologists, and law enforcement. By dint of their training and high moral standing, these men were believed to be immune to the depravity of the pornographic, and thus could peruse medical manuals, anthropological treatises, marital manuals, exotic literature, etc., without succumbing to their corrupting influences.

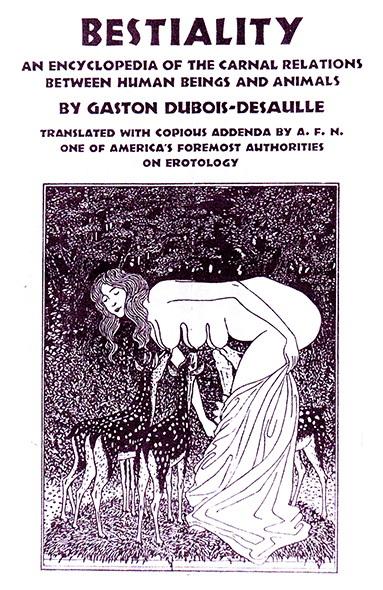

The sexism and classism in this view is self-evident, but it nonetheless created an opening that smut peddlers in the 1920s and 1930s exploited gleefully. The interwar period saw the rise of a number of mail-order publishers with names like the Hygienic Book Company, the American Ethnological Press, and so forth. Titles such as An Anthropological Cabinet of Curiosities (published by Falstaff in 1934) stressed the medical, learned nature of their contents, thus attempting to skirt obscenity laws. Falstaff Press boasted that its subscribers comprised “a Who’s Who of the Intellectual Aristocracy of America” and claimed that its readers were exclusively scientists, nurses, physicians, dentists, philosophers, ministers, and certified public accountants. In its marketing materials, Falstaff said it had a single “High Aim,” or “Vital Function”: to offer information regarding foreign and historical customs as a means of cutting down on sexually transmitted diseases as well as promoting the “health and pleasure of individuals.”

Falstaff Press and Panurge Press were the best-known of these publishers, and their books were also the best made. They make up a subgenre in the history of pornography that has largely been left behind: Too titillating to have any real scientific value, they often also had too much deflating scientific detail to be thoroughly useful to the average masturbator. The Anthropological Cabinet features photos of bare-breasted “Africans” and Japanese erotic woodcuts alongside stories of genital mutilation and diagrams of medical anomalies. These titles blurred the lines entirely between science and pornography. As Ronald Ladouceur writes, “In the first science-drunk decades of the 20th century in the United States, when open discussion of sexuality was severely circumscribed, by custom and law, efforts to understand and control sexuality—all the institution-funded studies of prostitution, journals on birth control, books on eugenics, lectures on proper marital relations, plays and movies about venereal disease, etc.—mutated in meaning to become themselves a kind of erotica.”

Attempting to straddle the line between both the learned and the prurient, these books were mostly incapable of satisfying either. At the time, though, they were fairly successful, at least financially. (Falstaff had revenue of $100,000 in 1939 alone.) As obscenity laws changed in the United States, these works have since fallen into obscurity because the artificial constraints that brought them into existence have ceased to give them meaning. But they remain a remarkable set of artifacts, a crystallized moment in the constantly mutable evolution of pornography, capturing a strange intersection of medical science and pandering.

Noteworthy in my collection is one title in particular: Praeputii Incisio, a book focusing on circumcision anonymously published in 1931 by Panurge Press. Subtitled A History of Male and Female Circumcision With Chapters on Hermaphroditism, Infibulation, Eunuchism, Priapism, and Divers Other Curious and Phallic Customs, my copy is rather handsome, with gold leaf lettering on the spine and the embossed crossed circumcision knives on the cover—far from the cheaply produced fare of most underground pornography. Praeputii Incisio is in fact an abridged version of an earlier book: Peter Charles Remondino’s 1891 History of Circumcision From the Earliest Times to the Present: Moral and Physical Reasons for Its Performance.

Rather than seeking to excite the reader, Remondino’s original book was part of a larger movement that captivated doctors in the last few decades of the 19th century—a movement to once and for all rid the male body of the foreskin. By the 1870s, well-respected doctors like Lewis A. Sayre, who went on to become president of the American Medical Association, were claiming that many childhood ailments could be cured by circumcision. In 1875, Sayre argued that the foreskin could produce “an insanity of the muscles,” and that these insane muscles could eventually come to act “on their own account, involuntarily ... without the controlling power of the person’s brain.”

Remondino was himself an established and respected physician in California. He had been the first president of the San Diego Board of Health, and vice president of the California Medical Society. He was also a crusader; he took up Sayre’s banner (he referred to Sayre as “the Columbus of the prepuce”) and argued strenuously against the uncircumcised penis. The goal of his magnum opus, as he put it in his introduction, was “to furnish my professional brothers with some embodied facts that they may use in convincing the laity in many cases where they themselves are convinced that circumcision is absolutely necessary,” and particularly a concept of “preventive surgery,” so as to ward off the innumerable dangers that accompanied an uncircumcised penis.

Panurge’s abridgement of Remindino’s History includes much of the first half of the book, but largely cuts out the second half—most of which is Remondino’s medical argument. Chapters like “The Prepuce, Syphilis, and Phthisis,” “The Prepuce, Phimosis, and Cancer,” and “General Systemic Diseases Induced by the Prepuce” are removed or heavily edited; cringe-worthy case studies of gangrenous penises and other medical horrors are removed from their clinical context and sandwiched into the historical chapters. It’s not entirely void of Remondino’s original moralizing and recommendations: “We have already observed in previous chapters,” writes Remondino in one of the passages retained in Panurge’s edition, “how the prepuce interferes with the growth of the penis, occasioning in its wake many disorders resulting in impotence.”

But Panurge’s Praeputii Incisio is far more focused on “exotic” foreign sexual practices, and salacious anecdotes from Remondino’s practice. If one is expecting the rest of the book to carry on in the same tone of objective scientific discourse, what actually follows through much of the book is a grand guignol collection of diseased members, phallic cults, eunuchs and castrati, female circumcisions and cliteridectomy as a means to cure female masturbation, and other extreme genital violence—including the lengthy passage describing a botched circumcision.

What to make of such drawn-out, scientifically useless passages that proliferate through the book? Without doubt, reading Panurge’s Praeputii Incisio can be an uncomfortable, unsettling and frustrating experience. Even as the book advertises itself as a “history,” it’s clear that a violence is being done to the term, and what lies within is less a history than a rambling, incoherent polemic that has been cut in half so as to become even more incoherent. The book itself reads much like a botched experiment—these anecdotes and facts are so strangely removed from Remondino’s original, polemic intent, and yet don’t even have masturbatory value, leaving a book that seems to singularly fail at almost every task it sets for itself.

But the original is arguably much worse, containing even more vile racial and misogynist assumptions, and sold under the aegis of medical learning. Remondino’s ranting, polemical and disjointed style would hardly be acceptable in today’s academic discourse. But it also made him particularly vulnerable to a pornographer like the publisher of Panurge, who could easily repurpose his rambling anecdotes to his own ends. Panurge’s butchering of Remondino’s text, slicing off its context and moving it from medical learning to borderline pornography, ends up activating it in a different way. It is bad history and worse science, but it no longer has any pretensions to belonging respectably in either discourse.

Ultimately, Panurge managed to completely upend the original purpose of Remondino’s text, because if there was a malady that doctors like him were most obsessed with, and most interested in protecting children from, it was masturbation itself—Panurge’s stock and trade. For while circumcision may ward against diarrhea, syphilis, and cancer, its advocates’ true purpose was to protect against the great scourge of self-pollution. Numerous medical authorities recommended circumcision as a means to curb masturbation, from cornflake inventor J.H. Kellogg, to Robert Tooke’s best-selling 1896 parenting guide All About Baby, which advised circumcision to prevent “the vile habit.”

Despite the problematic science invoked by the early circumcision crusaders, the practice caught on, and by the end of World War I had become the most common surgical procedure in the United States (as it still is today). Several studies suggested that Jews had lower rates of disease, particularly cancer, leading men like Remondino to seize on ritual circumcision as a contributing factor in their longevity. Other studies suggested that circumcision could reduce rates of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. At the same time, advances in anesthesia and a better understanding of germ theory allowed surgeons to convince the public that circumcision was both painless and safe.

However, circumcision was best done on infants before any self-polluting practices could take hold. David M. Friedman, in his A Mind of Its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis, notes that, “as infants could hardly be deemed immoral, [these recommendations] implied that masturbation was less a character failing than a reflect response to a physiological problem—a design flaw, as it were, that could be corrected.” Remondino concurred, and his attitude towards the relationship between circumcision and masturbation could not be clearer. “Circumcised boys may,” he writes, “in individual cases, either through precept or example, physical or mental imperfection, be found to practice onanism, but in general the practice can be asserted as being very rare among the children of circumcised races, showing the less irritability of the organs in the class; neither in infancy are they as liable to priapism during sleep as those that are uncircumcised.” This passage, however, does not appear in the Panurge edit, though Praeputii Incisio does have a few things to say about masturbation, including a salacious tidbit regarding the ancient Scythians: “These men had previously been eunichized by a process of continued and persistent onanism, which at length caused the complete atrophy of the testicles.”

The difference between the two contexts is noteworthy: The anecdote about Scythias, in the context of Remondino’s “progressive” anti-masturbation argument, is just one more example of why circumcision should be widespread. But without Remondino’s explicit comment that circumcision curbs masturbation, the Scythian comment is just one more whispered urban legend in a handbook full of bizarre rituals and precious little medical advice. By cutting up and scrambling Remondino’s message, Praeputii Incisio manages to harbor a series of contradictory discourses within its covers: pornographic and prudish, scientific and titillating. Reading Panurge titles like this means experiencing a cacophony of diametrically opposed messages presented in a single book: a strange semantic jiu-jitsu in which Remondino’s message has been turned on its head and yet still exists as a ghost trace.