An Afro-Russian boy searches for hope and love in the labyrinthine Moscow metro in Hamid Ismailov’s The Underground

THE first word G. learns when he arrives in Russia is chornyi, or black. The next, the most frequent, is obezyana, or monkey.

It was just one word, he assures me. But repeated so many times, it accumulated weight and developed sharp edges. At least he wasn’t alone, he says. There were other guests of the Soviet Union, funded by and living under the protection of the government, students from many countries: Vietnam, Laos, Yemen, Cameroon, Angola, South Africa, Guinea, Mali, Congo, he names a long list. They treated us well, he adds; they were afraid who might be KGB. We were sheltered from the bluntest impact of racism by the Russian people’s wariness of each other, their own internalized fears and distrust. And remember, he continues, as bad as it was, we knew we had a home where everyone was just like us. When someone called me chornyi, I learned the word for white, biely, and shouted it back.

My cousin G. is speaking of his years as a student, when he left Ethiopia to attend first the Moscow Conservatory of Music, and then what used to be called the Leningrad Cultural Institute, where he would study photography and film. He kept a daily journal, he says, pages piling up as one year bled into the next. He wrote every day in Amharic, before stepping outside to slip into his Russian life.

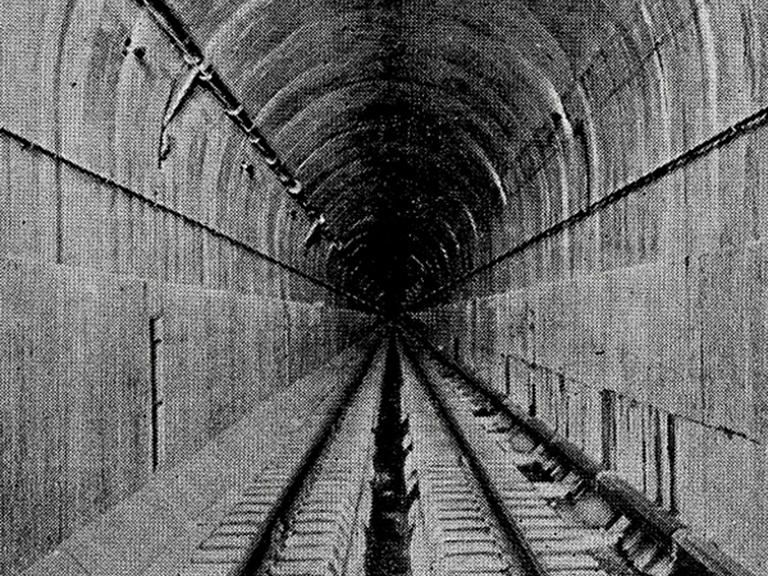

I ask him about the Moscow metro system, because I have heard of its stunning beauty. Because I have read Hamid Ismailov’s elegiac and powerful novel, The Underground, I wonder what it was like to go deep beneath the city of Moscow and travel through a metro system that some have called one of the most complex ever built. I wonder what it was like to be a foreigner and black in the confined spaces of the station and the trains.

G. tells me of the underground, of its vastness and breathtaking architecture. If one did not know the system well, he says, it was easy to get lost in the labyrinth of tunnels. There were days when he wandered unsure beneath the city, so disoriented that he went hours without seeing daylight. I imagine this: G., still struggling with this new country, this new language, this new underground terrain, riding the metro from one stop to the other, one path snaking into the next, sending him in endless, looping circles while he tries, first in Amharic, then in his broken Russian, to make himself understood without inviting hostility and fear, without inviting ridicule and racism.

It starts to make sense that he switched out of the music conservatory to study photography and film: It was one way to feel like he belonged, to communicate with a degree of fluency in at least one kind of language, a visual language. He was afraid to speak English, he tells me, and until his Russian improved, he was reduced to using gestures. An image comes to mind: a black man in the Moscow metro pantomiming and gesticulating, movements growing larger and more exaggerated as one hour blends into the next and he finds himself again at the wrong station.

G. is a gentle man, with a sharp intelligence and soft eyes. He is the chronicler of our family history; he was writing long before I was. I do not want to imagine him lost. I do not want to think of what kinds of responses he might have gotten that kept him in the underground, wandering, for so long. It is better to think of him in Leningrad, carrying his Kiev camera around his neck, focusing his lens, capturing a moment, fully in control.

Things got much worse during the transition, G. continues. He is talking about the days of perestroika, glasnost and Gorbachev, which many associate with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rush of new freedoms. Those days when everything started to loosen, when a society that had once been held in a tight-fisted grip found room to breathe. Pent-up resentments no longer had to be contained, and the fine balance between the calm instilled by a secret police and a fearful public was ruptured. The formalities that had protected African and Asian students suddenly became tenuous. Police protection disappeared. Racial violence escalated at a startling pace, with a shocking intensity.

G. knew he had to leave. By 1991, he was able to get out.

It’s hard to imagine what it might have meant to be black in those days when a whole way of life was unraveling. Difficult to fathom where he could find refuge when nothing seemed to be standing still. I see this: G. in the Moscow metro system, disoriented and lost, descending deeper into a bottomless city as seismic shifts rumbled above. It plays out in my mind like a clip from an old black-and-white film, cinematic and nightmarish, a tense scene unspooling against a roiling political backdrop. It feels unreal and surreal, vivid and also lonely. But when I look again, I see my cousin maneuvering his way out, climbing from darkness to light, breathing the fresh air of the city, then when the turmoil escalates, escaping out of it altogether. Safe.

What could it mean to be Russian and black, with nowhere to go? Hamid Ismailov sets his heartbreaking The Underground in this reality. The narrator, Kirill, nicknamed Mbobo, also sometimes called Pushkin, tells us of his life in a voice speaking from the dead: “I am Moscow’s underground son,” he says, “the result of one too many nights on the town.” He is the offspring of an African athlete and a young Siberian woman, conceived during the 1980 Moscow Olympics and born nine months later. His father returned home; his mother (nicknamed “Moscow”) died when he was eight. With brutal frankness, he tells us that he, too, died four years later, at the age of 12. “That is all there is to my Moscow life. The rest is just decaying, late-blown blooms of memories.”

His dead voice leads us through the novel, each chapter bearing the name of one of Moscow’s metro stations. As we follow Mbobo through the underground system, his story unfolds against one of the most beautiful underground systems in the world. Ismailov’s tale of intense loneliness is linked together by Moscow’s subterranean city. Every significant memory, every pivotal event in Mbobo’s life occurs in the rhythm and rattle of the metro station. And as the story progresses, we begin to understand that the narrative is also about this boy’s search for enduring love. We know he will eventually die, but what matters is whether he will ever experience the deep sense of belonging that he seeks.

Never in my life, my life on the other side, on the surface, had I seen such beauty, such splendor…This world entered my pounding heart in tremors, and I felt that no one would be able to drag me back from this world or this world back out of me…

When the idea to build an underground system in Moscow was first proposed to the city council in 1902, it was met with fierce resistance. Rumors say that its failure was due in part to the Russian Orthodox Church’s strenuous objections to tunnels beneath its churches. They argued that it would be the work of the anti-Christ. It isn’t difficult to guess what might have been the Church’s hesitation. Tunneling beneath sacred ground could disrupt the hallowed resting place of the dead; it might inadvertently lead to the construction of a kingdom of evil, a middle ground where unsettled shadows could wander through the darkness seeking light.

Decades later, when the subject was broached again, there were other, more immediate reasons it should have been impossible for Russia to build a metro system. For starters, no one knew how to build one. The USSR was also experiencing a severe shortage of labor and building materials. Construction machinery was so difficult to get that it could be considered nonexistent. There was no reason to think that the plan would work. It was an irrational dream that bordered on the audacious.

When construction moved forward in 1931, it was slow, uneven, and came at a tremendous human cost. But when it was completed, the Moscow metro system would be one of the most spectacular in the world, each station a stunning architectural and engineering achievement, a testament to an artistic vision that should not have succeeded.

The beauty of these Stalin-era stations lures young Mbobo to the underground. Aboveground, he is the target of racist cruelties, both passive and aggressive; below, he imagines that he can ease into the dark pockets of the subway system and blend in. He stands, impressed, before the mosaics and statues, and lingers in the golden light of intricate lamps. It is magnificent enough for him to believe in the impossible, to believe that in the darkness of the underground he can leave himself and his black body behind. That in the metro, he can simply exist: neither Mbobo nor monkey, neither Pushkin nor fatherless. Just a boy sliding through a space that carries no judgment with it.

It is what he would like to imagine, but Ismailov does not offer easy compromises. He asks difficult questions about belonging and identity: there is racism, still, in the metro, and Mbobo cannot leave any part of himself behind. But there is also freedom, a sense that he can travel beyond his everyday existence; that he can escape into the world of his imagination. It is a young boy’s dream, an idealist’s ambition: to travel fast and far and arrive, always, in a place of beauty and greater safety. And Ismailov’s decision to set this story in a space that crisscrosses Moscow, a place firmly rooted in Russian history and pride, is a radical statement about Mbobo’s claim to his identity. This boy, this black boy born of an African and a Siberian, is very much the son of Moscow. He does not need to be anything other than what he is.

But where do you go to see a likeness of yourself, your Russian self, when there is no one else like you? Mbobo finds some relief in the fact that a statue of Russian writer Maxim Gorky is chiseled from brown stone and “so, the color of his face was similar to mine.” But it is the ever-looming presence of Alexander Pushkin in the Russian imagination that has become a burden for Mbobo. Pushkin is, to him, a “most painful secret: starting from kindergarten, people didn’t nickname me Blackie… not Monkey or Macaque and not even Chocolate, but…Pushkin.” Mbobo contends that Pushkin is not Russian enough, and he rebels against this too-easy comparison to someone who is less Russian than he: “just as he was an Abyssinian by his great-grandfather, Ibrahim Gannibal, so I was a Russian by my grandfather, Colonel Rzhevsky.” When he looks into his own face, he sees his Russian features, he sees his mother’s eyes staring back at him. Her identity, her lineage, declares his own. And when she dies, as we know from the beginning she will, she must, we begin to also sense what her absence means for Mbobo and his future.

I did not so much understand as guess…that we hadn’t lost our way among those three stations, nor among three trees, but among our lives: among body, legal codex, and spirit.

Mbobo’s mother has been coughing for months before anyone realizes that her illness is a result of the “radioactive alien intrusion” from clouds from Chernobyl. And it is as they rest in the alcove of a pillar in the hall of Ploshchad Sverdlova Station, the coolness of the marble soothing Moscow’s lungs, that Mbobo guesses for the first time that one of them is going to die soon.

Here is the chapter that comes soon after that, in Taganskaya Station:

And suddenly Mommy wasn’t there…

And here is Mbobo in Ploshchad Nogina Station:

…and Mommy wasn’t there…

And the following chapter, set in Ploshchad Nogina Interchange, contains the unspeakable as it becomes a realization:

Ismailov balances moments of startling clarity with a child’s inability to articulate devastating loss. It is one of the hallmarks of his writing in this novel, this deft handling of a wry, speaking-from-beyond-the-grave voice—a ghost with nothing left to lose—and the visceral, unfathomable emotions of a lost child. Evocative details, coupled with a world-worn irony, lend Ismailov’s prose a razor-sharp perceptiveness that is both weighted and symbolic. As chapter after chapter progresses and incident upon incident piles up in Mbobo’s life, we, too, begin to yearn for a thread of hope. We, too, wander the underground with him, searching for points of illumination that can withstand the glare of daylight.

When Mbobo begins to feel the first tugs of love in the form of a girl named Zulya, the momentum of the novel surges, and it is easy to believe that Mbobo might overcome his own tragic end; that the voice that speaks doesn’t come from a place beneath the earth, where dry bones quiver with the reverberations of another train zooming by, far below. And even when the world Mbobo knows begins to disintegrate in the era of political transitions and upheavals—those days of perestroika and glasnost—Ismailov renders a narrative so rich and complex that we give ourselves license to believe that there will be something left after it ends, something worth all the pain.

If redemption is there, Ismailov suggests, then it rests in the literary and the imagination. Midway through the book, Mbobo examines the lives of Alexander Pushkin, with his Abyssinian background, and Leo Tolstoy. Which one is more Russian? No matter who they were, he decides, in the end, “what is left is literature, a heroic attempt to balance an unbalanced life, an unbalanced soul.” I’m reminded of something else G. said. The Russians were readers, and they had a deep and profound connection to literature that he admired. Even his residence in Leningrad, he points out, was across the street from a metro station, Chernaya Rechka, named in honor of the place where Pushkin fought his last duel. The Underground, too, is steeped in Russian, and Soviet, literary tradition. The structure of the novel echoes Yerofeev’s Moscow to the End of the Line, and Ismailov seems almost gleeful with his many sly literary allusions, from Abkahazia’s Fazil Iskander to Nobel laureate Ivan Bunin. “Fathers and sons…” Mbobo says, referencing Turgenev’s novel, Fathers and Sons, “but for me it was Fatherlessness and Orphanhood.”

At the planning stages of the Moscow metro system, many stations were designed to conquer the claustrophobic sense of being underground. Stations were built to give the effect of light streaming from above, to allow subway passengers to believe that the sun could brighten the subterranean city. Ismailov’s novel, despite its tragic tenor, also offers glimmers of respite. It is a testament to the book’s grand vision that through to its wrenching and inevitable end, we are never left to wander long in its stretches of darkness. There are always bursts of light to guide us forward, to allow us to imagine while illuminating all the possibilities that await those who never give up on hope.

After we talk, G. sends me a short note. You have reminded me of those good old days, he jokes. And he tells me of the beauty of the parks and the architecture, of the astounding culture and the museums. Then he adds, I am searching the complicated web of the Moscow metro lines to remember more things.