It is often said of fiction that it is “impossible to put down.” The suggestion is that what we want from reading is total submission: we should turn pages like an alcoholic drinks a six pack. Though there is pleasure to this kind of reading, there is fear in it too—if you were to put the book down you might never pick it up again. A novel’s world is tenuous, desperate. A reader who literally can’t put a book down is an addict, a consumer, a slave to the comforting pleasures of met expectations.

In The Pleasure of The Text, Roland Barthes describes two kinds of texts, distinguished by the kind of pleasure they produce in the reader. There is the ”text of pleasure” that “contents, fills, grants euphoria…that comes from culture and does not break with it” and there is the “text of bliss,” which “unsettles the reader’s historical, cultural and psychological assumptions, the consistency of his taste, values, memories, brings to a crisis his relation with language.”

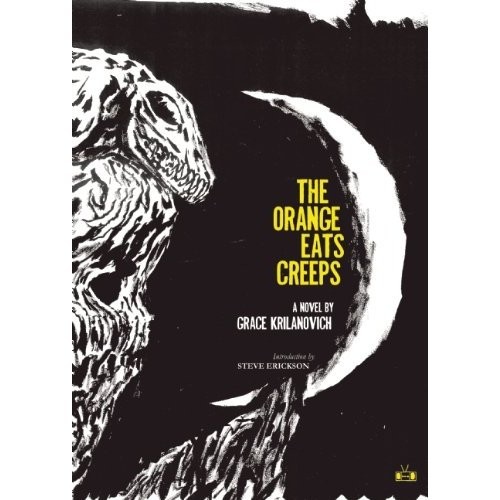

Grace Krilanovich’s The Orange Eats Creeps is a text of bliss: you can’t help but put it down. With its short length, you could read this disturbing, beautiful debut novel in an afternoon—but the experience might be awful. Orange is a book best read fitfully or in deep silence. The style, when the mood or atmosphere is right, can be transcendent. Other times it is exhausting. Best to steal a page here, five there. Include many moments of silent sitting, your finger holding your place, trying to decide if you’re thinking about the book or maybe a horror movie you caught on TV the night before.

The novel’s protagonist is an unnamed seventeen year old girl in the thralls of addictive hallucination, engaged in a search with no object. She claims to be a “Slutty Teenage Hobo Vampire Junky.” She might have drug induced ESP, she might be engaged in deadly battle with a Warlock, she might have a psychic connection with the bones of a rat-cat that she keeps in her filthy apron, or she might just be a drug-addled gutter-punk foster-home-runaway stalked by a serial killer in the Pacific Northwest.

Orange exists on a visceral plane. It is narrated as if by a body wresting the controls from an irrational mind. In the early sections, she hops freight trains with a gang of four male friends, shoplifting from supermarkets, puking in convenience stores, going to basement punk shows and laying out at punk squats, prostituting herself for cash, drinking booze and taking all sorts of drugs. Lest this sounds too serious, these desperate pleasures are often played against incisive fatalistic comedy: “This was one of the famous Meth squats of Irondale, a real mustache on the face of depravity.”

But the solitude of this angry narcotic chaos eventually manifests itself. One by one the boys in her gang disappear, though you don’t notice they’re missing until they’ve been gone some time. Slowly, the curtain of punk-rock fury and hip self-destruction lifts to reveal the narrator’s frightened loneliness. She picks up garbage, wanders through forests and empty town centers, looking for ‘clues’ to the whereabouts of her foster sister Kim, who, we learn very early on, is dead. “I noticed tiny numbers encoded on every surface,” the narrator says. “Strange dates on bridges and tiny plaques like metal scabs all up and down telephone poles. Cryptic codes I would never know encircling hieroglyphs made for some race of secret vagabond police.” Her search is at once a literal search for the zombified body of Kim, a mystical attempt to communicate with her ghost, a grasping for the familial stability and cultural understanding her foster sister provided, and a dirge for the innocence permanently lost to the horror of her junkie life.

These narrative contortions don’t smack of cheap opacity, empty gestural avant-gardism, or hipster sensationalism. Rather than the standard vicissitudes of plot and character, Krilanovich builds a psychical and stylistic arc, which takes us, chapter by chapter, layer by layer, further into the narrator. Orange starts out in a mode of punk-rock horror nihilism—Poe rewritten by David Lynch at a Flipper show—but just as this begins to grow tiresome, the language changes tack. Though the narrator’s experience remains debased and ugly, a resonant, poetic, Imagist style emerges.

Krilanovich uses these stylistic shifts to reflect how the clichéd iterations of the narrator—rebellious mask hiding sensitive girl—are constructions, psychic defenses against the void. We sink into the turmoils of her budding personality, watching an ego desperately try to rationalize the disorienting, visceral experience of her unconscious:

A disembodied voice arrests me. I am unable to move. The sound vibrates all the fluids of my body, creeps out of my blood and into my bones. I could be your lover, let’s pretend!… A silly moth flutters against the wickedness of a flower moon, rising against a trough for cats to drink from while mamma’s away…It seems logical that the future body will be one that is more storable, able to be stashed and stowed away at the convenience of the stower. (ellipses and emphasis original)

Exterior space is replaced by the surrealist blur of a body and mind too aware of their fusion, a crisis of identity which never rages so strongly and confusingly as it does in adolescence.

In many ways, Orange is a novel about the horror of physical experience; about the organic and psychic detritus of an alienated world; about eating the self and shitting it out; about consumption, apocalypse, and fear. “This is progress, I thought. They have won. Real-life has been successfully shackled and hogtied and displayed in the city plaza…I Just want it to be real—I’m ready to make it that way…And as I said these words the skuzzy vacuum sucker that spat blood all over my hair raised itself on its elbows, pulled out an extension cord, plugged up the hole where its belly button had been, popped 38 Excedrin, and quietly died.” Hers is not a world dying, but a world already dead.

It’s also about a teenage girl trying to fuck her way to truth, to turn the objectifying gaze and desire of men into power, a vampire in the realest sense, a filthy, desperate coming-of-age tale in an undead world. There’s a lot of sex, and not much of it is pleasant. “I felt like I was close to unlocking the secret look of male desire, the one that says not ‘I want to fuck you’ but ‘I want to keep you.’ I was sure it was a different look. There was a difference but it flickered in and out of my sights. But I didn’t know what the fuck I was talking about. I only had a partial view.” Sex mutates from a form of self-preservation, as she prostitutes herself in the opening chapters, into a form of intoxication, as she stumbles narcotized from strange man to strange man, until it finally becomes a tool of individuation.

If The Orange Eats Creeps is in turns existentially frightening, sumptiously beautiful and hilariously funny, it can also be tremendously frustrating to read. But it is that rare, important kind of frustration: not that the novel doesn’t suit your tastes, but that your taste doesn’t know what to do with this novel. It’s a novel that teaches new ways of reading, and points towards a poetic fiction meshing genre, form, image and psyche into a tangled, hallucinatory, beautiful mess.