On April 28th, the Museum of Innocence, the long-awaited realization of Orhan Pamuk’s novel of the same name, opened in one of Istanbul’s more bohemian quarters. But let us not begin with the Museum of Innocence or The Museum of Innocence. Rather, let us begin with the word museum. It comes to us from the ancient Greeks, who created a temple to the muses at Alexandria, the Mouseion. As a site of remembrance, it suggests an almost Montaignian retreat inside oneself; this makes sense, given that “museum” stems from the Indo-Germanic root /*mon/ meaning “to think” or “to remember.” In a modern museum, these acts of thinking and remembering are publicly introspective motions, and this retreat inside ourselves becomes a collective affair. We are alone with our thoughts, together.

None of this is news to Kemal, the protagonist of Orhan Pamuk’s novel and the (fictional) founder of the (real) Museum of Innocence. He spends all his time thinking of Füsun—a poor shop girl 18 years his junior—and plotting ways to extend their dalliance. Their affair seems destined to end as quickly as it began, however, for the 30-year-old Kemal is engaged to another girl “who, according to everyone, was the perfect match.” But as the law of probability and necessity requires, Kemal and Füsun fall madly in love, the kind of love that undoes the perfect engagement, ostracizes Kemal from high society, and condemns him to eight years of anguish and awkwardness, during which his wistful reveries of Füsun hardly abate. In an effort to ingratiate himself to her family and atone for his misdeeds, Kemal dines with Füsun and her parents for 1,593 nights. (He counts.) There’s just one complication: at the dinner table also sits Füsun’s new husband.

Kemal initially thinks this is a sick joke (her husband is a “fatso”), and is emotionally undone but remains undeterred. Over the course of these 1,593 painful evenings, Kemal, a businessman who can also name-drop Proust, Dostoevsky, and Nabokov, oscillates between states of madness, desire, and frustration. This is all in his head, of course, for not much action actually takes place at Füsun’s old home. With their family, Kemal watches old Grace Kelly films. He drinks rak?

During those eight trying years, Kemal could have used a number of things—family support, diversions, a good therapist. But given his diverse and impressive literary sensibilities, it might not be too grandiose of us to say that Kierkegaard’s Repetition could have changed the course of his entire life. Like Kemal, the protagonist of Repetition falls under the same spell of recollection, enchanted by thoughts of an obsessive love that also doom him to a broken engagement. But while Repetition reads as a cautionary tale (and doubles as autobiography: Kierkegaard left his fiancée too and lived sorrowfully ever after), The Museum of Innocence, at first glance, embraces this dangerous penchant. Kemal’s museum, in its commemoration (or objectification) of Füsun, aspires to never transcend the past: “the Museum of Innocence was to be a place where one could live with the dead,” Kemal tell us.

Kierkegaard makes the salient distinction between the states of repetition and recollection, the former salutary, the latter dangerous. For Kierkegaard, repetition entails reliving the joys of an individual moment, anticipation included. Recollection—the disease Kemal so acutely suffers from—conversely entails reimagining the memories of the past, plangent or pleasing. Over, done with, finished, the beauty and joy of these moments is only to be remembered. And remembrance of these moments, for Kierkegaard, is sad: “recollection is a beautiful old woman with whom one is never satisfied at the moment; repetition is a beloved wife of whom one never wearies for one becomes weary only of what is new.”

The Museum of Innocence is inextricably tied to Kierkegaard’s notion of recollection and its corresponding unhappiness. “Recollection has the great advantage that it begins with the loss,” says Kierkegaard. “The reason it is safe and secure is that it has nothing to lose.” Kemal has the great advantage that he, too, begins with loss. In terms of collecting Füsun’s household items during his thrice-weekly visits to Füsun’s house, the reason he is safe and secure is that he has nothing to lose.

Kierkegaard would lambast Kemal’s project as selfish. “He who will merely recollect is voluptuous; he who wills repetition is a man,” he says, before telling a story that tracks the plot of The Museum of Innocence.

2.

In his essay “No Ends in Sight,” Bard professor Thomas Keenan locates the museum as a generative space of grief. “Museums are built on loss and recollection,” says Keenan. Loss, while potentially devastating for the curator, inspires the museum, for “we can say that the museum finds in loss its most powerful alibi. Elsewhere, something is said to be nearing its end, threatened with extinction, and demands memory and protection. There is inevitably something of the cemetery and the epitaph where the museum is concerned.” In other words, the specter of death animates the museum.

Keenan continues, saying, “Loss and the fear of destruction, especially after the fragility of a collective identity, is a terrible stimulus to preservation.” Without giving too much away, this explains Kemal’s feverish quest to collect Füsun’s belongings. Keenan’s notion of collective identity is also germane, considering Kemal often remarks about the physical sense of communion the two shared: Füsun literally resembled him. The fusion of identity and notion of doubles, among Pamuk’s favorite themes, also introduce a sort of physical repetition at the level of character. Füsun repeats Kemal. This repetition marks a rare departure from the haze of recollection that accompanies all of the book’s discussion of the Füsun and the museum.

“The museum,” for Keenan, “wants to be a salvational and sheltering institution, a machine for preservation and transmission, an archive of what is lost or at risk of disappearing and a mechanism for reanimating it.” The salvational aspect is twofold here: not only is Kemal trying to preserve Füsun’s memory, but he is also attempting to redeem himself after having fallen out with society. Keenan perhaps also reclaims Kemal from Kierkegaard’s critique, for recollection has the potential for “reanimation,” the sort of vivacity that underpins his concept of repetition.

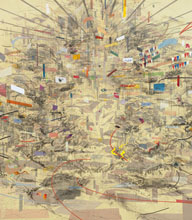

Further, Keenan adds, “Museums shelter not so much objects as meanings, and their work is that of articulating, linking and arranging them in a network of significance.” The physical Museum of Innocence may contain 237 hair barrettes, 419 national lottery tickets, one saltshaker, and 4,213 cigarette butts, but only collectively do these objects form a network of significance. This is not to understate Pamuk’s desire to recover the marginal—he recently told the Financial Times, “we’re preserving things that were never represented, underlining commonplace, daily-life qualities”—but in terms of Kemal’s broader project, it is the totality of these ephemera that produces his mental image of Füsun.

3.

The top floor of the museum—a well-attended converted apartment whose red façade mostly meshes with the surrounding residential architecture—displays Pamuk’s early drafts and drawings, in addition to a bed ostensibly belonging to Kemal. While this floor is comparatively smaller than each of the preceding floors in terms of size and ornament, it is one of the most significant parts of the museum. Here, casual visitors who may not have read the book get a taste of Pamuk’s trademark metafictional sensibility—whether they realize it or not. Near the bed, a caption notes that Kemal lived in this room between 2000 and 2007 while Orhan Pamuk listened to his story. It is not clarified whether this is Orhan Pamuk the character or the author. I lingered long enough in this room to witness the dismay of a few visitors at this perceived sleight-of-hand—Pamuk (the author) had billed this as a fictional museum, and now the last exhibit had upended their expectations: So this was a true story, after all? He didn’t even make it up? Not quite: at the end of the novel, readers learn that The Museum of Innocence is actually narrated by a character named Orhan Pamuk, who is telling Kemal’s story for him. That Pamuk (the author) omitted this crucial detail is no attempt to cruelly mislead less perspicacious visitors; rather, this note exists in the service of metafiction, asking us to reconsider the rigid domains of fiction and reality.

The similarities between events in The Museum of Innocence and Pamuk’s memoir, Istanbul: Memories and the City further invite speculation and reexamination of the relationship between fiction and reality. To name just a few, we learn in Istanbul that the 19-year-old Pamuk used to rendezvous with his younger lover in a family apartment, just as Kemal and Füsun did. And after his lover is tragically sent away to Switzerland, the star-crossed teenage Pamuk still returns to the gates of her school every day in the hopes of seeing her; this heartbreak possibly served as inspiration for Kemal’s endless visits to Füsun’s former residence, long after she’s gone. Istanbul also may suggest that Pamuk’s fascination with doubles

Pamuk is aware of our awareness these similarities, but refuses to confirm or deny the reality of any scenes from his fiction. “We always ask this question: Did the writer invent this, or is it that he experienced this? Is this the strength of his imagination, or is that how interesting his life is? And there’s never an answer,” he told the New York Times when the museum opened in May. But even if he could answer these questions, he would keep the so-called truth to himself, for “the power of the art of the novel lies on this question of the ambiguity between fiction and reality.”

4.

For Nietzsche, Kemal has wasted his life—or, rather, hasn’t truly lived. “Without forgetting it is quite impossible to live at all,” he says in “On the Use and Abuse of History for Life.” Nietzsche predicts Kemal’s degeneration into melancholy in which the “historical sense no longer preserves life but mummifies it,” railing against the “repugnant spectacle of a blind lust for collecting.” In the modern, Western sense advocated by Nietzsche, the museum can enable memory and generate pride, strength, and clout; however, when abused as in the case of the Museum of Innocence, collection can cripple its curator. But how do we reconcile the stern advice of Nietzsche—and Kierkegaard, for that matter—with the last lines of the book?

Kemal regards a photograph and kisses the image of Füsun, the woman who has caused him so much anguish over the majority of his adult life. Speaking to the character of Orhan Pamuk—who, as we mentioned, turns out to be the actual narrator of the book—Kemal lets out a “victorious” smile and says, “Let everyone know I lived a very happy life.”

This, at first glance, is doubtful. How could Kemal, the brooder par excellence, the one who visited his beloved—and her husband!—for eight years, the one who has been ruined socially, physically, and economically by lovesickness, so confidently tell the reader he has lived a happy life?

The answer lies in the novel’s complex temporality. Kemal explains to Pamuk: “In Physics Aristotle makes a distinction between time and the single moments he describes as the ‘present.’” Consider for a moment each object in The Museum of Innocence, and then consider the power of each object to encapsulate one such “present” moment from Kemal’s past. “Single moments are—like Aristotle’s atoms—indivisible, unbreakable things. But Time is the line that links these indivisible moments. Though Tar?k Bey

Here Kemal identifies the essential psychological struggle of his existence. Unlike Kierkegaard, who is worried about succumbing to the siren song of recollection, Kemal has no qualms about plumbing the depths of his memories of Füsun. What concerns him more is remaining within the present moment, and in order to achieve this he avoids thinking about the bigger picture, the Milestones or Life Events that organize our existence. In an Aristotelian sense, then, Kemal evades Time: “My life has taught me that remembering Time—that line connecting all the moments Aristotle call the present—is for most of us a rather painful business…but sometimes these moments we call the ‘present’ can bring us enough happiness to last me the rest of my entire life, and it was to preserve these happy moments for the future that I picked up so many objects large and small that Füsun had touched, and took them away with me.” While Kemal loses his sense of the Time that whirrs inexorably forward in the background, he can still make time. Time to forget the West, time to remember the indivisible, unbreakable moments of those 1,593 evenings, time to regard her 237 hair barrettes, 419 lottery tickets, one saltshaker, and 4,213 cigarette butts.