Is Indian history—or are Indians, for that matter—actually real?

For most non-Natives, Indians exist first in the imagination and then in the historical past. But every once in a while, the North American public is compelled to confront the living Indian in the material world. Last winter, for instance, the Idle No More movement brought large numbers of Indians into places associated with the modernity and mobility of white citizens: shopping centers and highways. These actions forced people who might not have thought of themselves as settlers to witness the grievances of Indians who consistently refuse to disappear. Another kind of testimony about the actuality of Indians emerged at the same time as Idle No More, also aimed at the unaware settler. Thomas King's The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America seeks to enlighten the settler by dispelling the fog that so often hangs around Indians and their relation to the nation-state. First published in Canada where it has become a national bestseller, the book seems written as a last chance for King, a respected public intellectual in Canada of Cherokee and Greek descent, to give his view of how Indians came to be, and what they will become. As a history of Indians told as one Indian’s conversation with himself, it is certainly a more illuminating and bold account of settler colonialism than the usual Indian history told as one white man’s conversation with his own desires.

For most non-Natives, Indians exist first in the imagination and then in the historical past. But every once in a while, the North American public is compelled to confront the living Indian in the material world. Last winter, for instance, the Idle No More movement brought large numbers of Indians into places associated with the modernity and mobility of white citizens: shopping centers and highways. These actions forced people who might not have thought of themselves as settlers to witness the grievances of Indians who consistently refuse to disappear. Another kind of testimony about the actuality of Indians emerged at the same time as Idle No More, also aimed at the unaware settler. Thomas King's The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America seeks to enlighten the settler by dispelling the fog that so often hangs around Indians and their relation to the nation-state. First published in Canada where it has become a national bestseller, the book seems written as a last chance for King, a respected public intellectual in Canada of Cherokee and Greek descent, to give his view of how Indians came to be, and what they will become. As a history of Indians told as one Indian’s conversation with himself, it is certainly a more illuminating and bold account of settler colonialism than the usual Indian history told as one white man’s conversation with his own desires.

But is Indian history—or are Indians, for that matter—actually real? Thomas King starts his account by questioning the entire premise of writing it. To begin with, there is the problem of “the Indian.” We all know who came up with that name. Though it is born from a mistake, it is the only term that seems to have stuck the longest for the most people. There have been attempts to correct the term—Amerindian, Aboriginal, Indigenous People, American Indians, First Nations, Native American—but as King says, “there has never been a good collective noun because there never was a collective to begin with.” So what connects all these people such that their history can be told in common? The answer is in the other collective noun King chooses to tell his story with, whites. There may be little that linked Mi'kmaq and Navajo people before contact, but now all Indigenous nations have a shared story of dealing with European invaders.

Thus Indian history, like the Indian, is born at contact. Even 500-page histories like 1491 that cover the time before contact are always oriented toward the moment when Indian existence would be recorded by Europeans—and these histories are categorized as "Pre-Columbian". Predictably then, King's story begins with Columbus (with a brief nod to the Vikings, officially the first Europeans to land in the land now known as North America). However, shortly after, on the advice of his wife Helen, who will appear throughout the book as King's editor, King ditches the chronological narrative passed down through elementary school classrooms and fast-forwards to other most prominent period in Indian history, the Indian Wars.

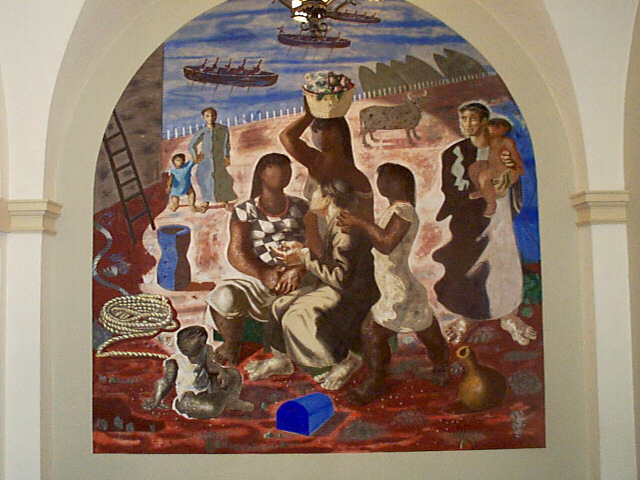

The Indian Wars are not as widely taught in schools, but the story of western expansion is deeply familiar to white Americans: the movie industry is based on it. King points out that in 1890 Thomas Edison chose Pueblo villages to be the first images he would record on his new motion-picture invention, the Kinetoscope. King places his emphasis on Native people and film “because film, in all its forms, has been the only place where North Americans have seen Indians.” Whether in the live theater of Buffalo Bill or Hollywood productions, Indians have always been at the center of the American imagination and a big source of entertainment. The sense of “capturing” something on film is not far off here; wielding the technology of film, many Westerners from Edison to James Cameron have tried to contain anxieties and attractions toward Indians by putting them on the screen in painfully predictable narratives. King goes so far as to say “Indians were made for film,” stressing just how hard it is for settlers to see Indians outside their exoticized representations.

These popular representations are conveniently one of tragic defeat. King dedicates an entire chapter to the famous statue “The End of the Trail.” You may not recognize the name, but you'd certainly recognize the image: an Indian warrior slumped over on his dejected horse, his spear pointed downwards. Looking as if both man and horse could fall over at any minute, the statue, King says, conveys the sense that “both the rider and horse have run out of time and space and are poised on the edge of oblivion.” But as he will throughout the book, King takes this tired old image and re-imagines it through Indian eyes. In a new reading of the sculpture, the horse is not buckling but bracing itself to resist and the doleful Indian becomes a “tired Indian, who, at any moment, will wake up refreshed, lift up his spear, and ride off into the twenty-first century and beyond.”

King's overtures to the non-Native reader are typical of Indian histories. By far the most popular book of the genre is Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Though a supposedly sympathetic perspective on history, one meant to highlight the atrocities and injustices of American settlement, Brown's book is also a very morbid tale. It lingers on the sheer number of Indian deaths and the horrible matter in which they occurred. It is of course hard to tell the history of Indian-white relations without mentioning the long episodes of genocide. However, by placing these injustices in a very specific time period, the Indian Wars and time of Western expansion, Brown consigns settlers' guilt to the past. Brown also very insidiously poses his book as being from an Indian perspective although he is white, reinforcing the message that all the Indians have died and it is up to sympathetic white men to tell their story.

While King's history is unique in that it is an Indian history actually written by an Indian, it repeats familiar colonial moves—it is still very obviously intended for settlers to read. King often bends over backwards to accommodate what he imagines will be his audience's unease at his anger. Right after he says “removals and relocations, as federal policies in [Canada and the Unites States], allowed Whites to steal Aboriginal land and push Native people about the countryside,” he allows that he should probably apologize for using the verb steal: “'To appropriate' might be more generous and less inflammatory.” Of course there is a bite to his concession. But it is significant that he has to couch his reasonable, accurate descriptions of how North America was settled in non-threatening jokes. The injection of defanging humor and aversion to objectivity are part of his project to write in a distinctly Indian voice. King acts very much as the grandfatherly ambassador. However, his irreverent tone and coy asides can make it difficult to discern just how serious King is about this history. The eighth time he makes a comment along the lines of “I should point out that Indians didn't do all the massacring,” the fealty to ignorance borders on insulting, either to the audience or to the people whose story he is trying to tell. But maybe that's what it takes to get settlers to read an Indian history.

The book, while scattered in chronology and even thematic cohesion, does progress to an increasingly bold critique. And the use of humor isn't always as reconciliatory as it is helpful for chugging through five hundred years of very bleak events. King seems to find the need to be funny not only to deal with the pain of retelling this history but also the dullness of it. Much of 20th and 21st century Indian history is told out as a series of Supreme Court trials. Indian law is purposefully convoluted and obfuscating, which can make it all the more dangerous. The legal labyrinths that often mean delayed or failed justice are especially harmful for Native women. In instances of sexual violence against Native women, for instance, the ambiguity of legal boundaries at the edges of reservations often stalls investigations while jurisdiction is sorted out. King brings up the case of Helen Betty Obsbourne, a nineteen-year-old Cree woman who was raped, beaten and then murdered by three white men who together stabbed her more than fifty times. Her case was not seriously investigated for fourteen years.

When the law isn't ignoring Indian women, it's usually plotting against them. Such is the case with Canadian Bill C-31, passed in 1985 as a amendment to the Indian Act, Canada's sort of catch-all legislation for defining who has Indian status and what rights that status warrants. Bill C-31 was supposedly meant to redress the sexist determinations of status under which an Indian man could marry anyone, Native or non-Native, and his children would retain status, while the an Indian woman who married a non-Native man would lose her and any children's status. Under Bill C-31, women could apply to have their status reinstated. However, the children of Indian women who marry non-status spouses would not have status. Already you get a sense of just how arbitrary and also convoluted Indian law can be. While the change C-31 introduces may seem minor, King argues that the bill, essentially a “two generation cut-off clause,” purposefully works to deny status to Indian children. The less Indians with status there are, the less people can claim lands held specifically and solely for status Indians.

Then there's Bill C-45, a bill which stripped not only the environmental protected status of hundreds rivers and lakes, but also opened up First Nations territories for corporate resource extraction developments. The passing of this bill is what sparked the Idle No More movement last winter, which saw round dances, a prominent chief's hunger strike, road blockades and countless teach-ins in Canada but also throughout the Americas and the world. It says a lot about the current state of Indian-White relations that a global indigenous movement could be sparked by the passing of a budgetary bill. But when a government can no longer wage open war against Indigenous populations, the courts become the tool to clear the land of Indian presence.

Unlike narratives such as Bury My Heart, King works to make clear that the injustices of American and Canadian settlement on this continent are not some distant tragedy but a continual process of dispossession and assimilation that continues to the present-day. In general, King is opposed to the word tragedy, perhaps the most common descriptor of Indian history and people. Tragedies are exceptional events, and King pushes the reader to see the injustices committed on behalf of settler governments not as aberrant but necessary to their structure as settler institutions. He presents the catalog of injustices, from the massacres and broken treaties to the residential schools and sexual assaults, but unlike white historians such as Brown, he does not leave them in the past. Non-Natives may know the history of these oppressions, but they are rarely considered as the ongoing basis for the very existence of North American governments and their citizens. This fact may need to be recognized before the settler can recognize the living Indian as something more than an inconvenience.

Yet even though King has shown Indians to be more than a collection of past tragedies, there is still very little about his narrative that offers Indians much agency. King himself notes, “Native history in North America as writ has never really been about Native people. It's been about Whites and their needs and desires.” It's unclear whether King is self-consciously describing his own work or not. But most of The Inconvenient Indianis spent exploring images imposed on Indians, laws applied to Indians and horrible acts committed against Indians, and very little on Indian resistance movements. It seems he may have fallen into the same trap. This may be a genuine reflection of what it means to be an Indian. The Indian was born at the moment of contact with whites, and for a long time Indians have been caught in that gaze. King’s book, in fact, recreates some of that gaze to narrate a convenient story to a white audience. But what might an inconvenient Indian do to break from this whiteness and create a truly Indian history?

Comments are closed.