The Twine-game designer on interactive fiction, “trash spinning,” and how to destroy the “completely unredeemable” games culture

Finch Kaye: To start off, can you talk about some of the games you’ve made?

Porpentine: I made a game called CYBERQUEEN, a sci-fi body horror incorporating my queer sexuality. It asks, What if the evil female AI won? And what if she was extremely horny? Cry$tal Warrior Ke$ha weaves together pop star Ke$ha’s personal mythology into this epic battle against trans-dimensional haters. How to Speak Atlantean explores my conflict-blasted body as a series of enormous mechanical zones followed by scavenging a hideous trashscape for spare parts to repair my broken Hitachi and cum my brains out.

I’ve made a game about communicating nonverbally with alien partners through the use of symbols, a game about hacking cupcakes designed to be played by a live audience, and an online multiplayer game about hungry ghosts sucking identity from the bodies of their fallen comrades to transcend the lamia-plagued plane of existence to which they are bound, to name a few. I made all of them in Twine.

FK: Tell me a little more about what Twine is. My sense is that it’s an important program because it’s so accessible.

P: Twine is probably the most accessible way to make games in the world right now. People who never made a game in their life are making games in Twine — people traditionally disenfranchised from game creation. It came into popularity because me and other queer women started using it.

Twine dispenses with a lot of the bullshit traditionally surrounding games — the gatekeeping, the obscure control schemes, the worship of high-end visuals over game play, etc. Twine is a really great visual environment. It lets you create your writings in nodes and connect them very spatially. It requires no code. I mean anyone can make a game in it in five minutes.

Twine is guerrilla warfare. It is cheaply-made pipe bombs and land mines that can proliferate and crop up in the dominant space. Besides being easy to create, it is not enough that our art be beautiful. It must be a beautiful weapon. We must ensure that our art is weaponized and can destroy other things.

We can flood sites and the Web with our games because it’s so easy to upload and share. There’s just no obstacle to playing them — you just load it like a webpage. We’re competing now with AAA games. That’s what I mean by weaponization. It’s hard to argue with that kind of viral, proliferating, breeding spirit.

Well, I guess I want to know what it is you want to destroy?

I mean, all of it. Just, all games culture. It’s completely unredeemable. The good games people have made will be around still. We don’t need any of the bullshit misogynist racist culture. Games journalism is toxic, games writing is toxic, game design — the most popular, the mainstream of it is just sick. It’s hard for me to answer that question, its just so big and virulent and there and monolithic.

You once wrote that creation is the most powerful criticism because it allows you to destroy what you critique. Could you expand on that?

Criticism is powerful too. A lot of my favorite criticism is legitimate art on its own merits, like Cara Ellison’s poem Romero’s Wives, which was later read by Anna Anthropy. And on the everyday level pushing back and being loud in our social spaces is important. We have to fight for every inch of our space. If we don’t we will be crushed by the insidious creeping tendrils of liberalism where every act of violence against a minority can somehow be justified.

That being said, what I meant is that our radical energies can be neutralized by pathological snark. It’s important to spend time with friends and alternative power structures, because otherwise you are purely locked into combating an oppressor whose goal is to make you feel insane. We have to take care of ourselves. Fighting and fucking. Basically, I don’t have time to explain to 1000 people about why I deserve to live and why being trans is beautiful, but I can make 1 game about it that 1000 people play.

How do you compose in Twine or construct experiences in hypertext? There’s a lot of that I don’t really understand in terms of placement of links as opposed to, say, poetry.

I’ve always just called it trash-spinning. Just like rolling up trash. But most of my games are just spontaneous improvisations where I roll up everything in my environment and I wad them together. They’re a big, crystalized trashy ball of everything that’s happened to me over the 24 hours or 48 hours in which I made the game. Like conversations, or you’ll notice how I incorporate all of the music I’m listening to in my games. It’s just very organic. Then I try to turn it into a weapon, something people can feel. How can my emotions be transmitted to another human being? A dart of nausea, arousal, triumph, crying, even radical, transformative joy.

What’s the place or role of music in these games? I mean, I’ve played Ke$ha Crystal Warrior, but —

Music is paramount: I make music games. Music is my surrogate emotion when I have none. I can’t emphasize it enough. I list the music I listen to while making the game because a lot of the games are actually kind of shrines to the music. They’re kind of hypertext music videos in some ways, Ke$ha being the most obvious example. But others are embodiments of the song in some way.

Recently you wrote a piece called “Seven Thoughts on Women in Games” in which you talk about making a Twine game called Howling Dogs, for which you were criticized. I think someone called it a crime. What was Howling Dogs and why did some people react that way to it?

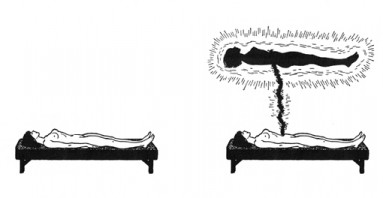

Howling Dogs is something — God, what a question. It’s a game that uses the central hub of being trapped in this tiny room, and you only have a daily regimen of base nutrition and hydration. Every night you go into a virtual-reality chamber and experience something that the artificial intelligence creates for you, and then you’re back again. The reasons are probably twofold, or threefold, for why people disliked it. In interactive fiction at the time, parser was dominant and people reacted strongly to nonparser work. Parser is like the old text adventures where you type commands to “go East,” or “pick up … fucko…”

Sword?

Sword, that’s better. “Fucko” is not a commonly recognized term. Whereas hypertext is clicking on links to navigate, and I guess it has superficial comparisons to choose-your-own-adventure books, yet it’s far more complex than that, as people are proving.

And really, we need both tools. Parser is adapted for expressing spatiality. For instance, the most popular parser authoring tool, Inform 7, posits everything within it as rooms with items inside them and actors where the default node that it creates is a room. Twine creates passages of words, which could be any kind of writing. Hyperlinks are just infinitely versatile. So while parser is created for spatiality, hypertext is suited to representing emotions and thoughts and more complicated things than mere physical space.

And I was able to play with physical space in Howling Dogs as well. The core is this physical space and then the exterior is arranged in all these dreamlike spokes. But to get back to what you were saying, another reason people disliked it was because I was a woman and I was trans and I had people specifically saying things or reading trans subtext into my work because they knew I was trans, which is a very cheap thing to do. People were commenting on the pictures on my site — talking about my game and also the pictures on my site in the same breath, like using the fact that I take erotic pictures — that I do queer erotic photography — as something against my game.

Earlier you told me about new game mechanics that people were developing. What are these, and do they show up in indie games in general?

There are a lot of interesting things people are doing with hypertext. Leon Arnott developed a lot of cool scripts for us to use. It’s like if you were a writer and suddenly you could make your pages play music or flip faster or change colors or have words melt mid-sentence.

Christine Love’s done some of the most experimental stuff with Twine. She has one where you don’t even click but your cursor’s a gun, and whenever you even hover over a link it just explodes! It’s a very volatile game. It just keeps going forward, propelled by your clumsiness.

In later games, the thing I’ve been impressed most by has been the cycling macro which actually lets you click on the hyperlink but it’s like a dial, so only the hyperlink changes. Previously in hypertext, how do you handle variables changing? You click on a link and you go to another page and there you set a variable. Whereas with cycling links, you have one page with words you can morph by clicking to change them around. It’s a way to give the player aesthetic agency. So it’ll say, “the sun is bright”, or “the sun is shrouded by clouds”, and you click it back and forth. And then you maybe click “and then I go outside”.

Controlling the world just seems so different from the normal control over what your character or your avatar in the game is doing.

Yeah, it gives the player a huge level of collaboration — which is what writing is in the first place. It’s saying, okay, what do you want this world to be? And you can just have it be aesthetic. It doesn’t have to show up later in the story and affect anything. I feel people feel the need to hard-code things. What people have been experimenting more with lately is just a more mercurial environment. I think people are going to be playing more and more with that. But that’s just one approach out of infinity. The important thing is giving people open-ended tools so they can surprise us. I just want to be surprised.

Some people think games have to be about surmounting a challenge —

[ppffff]

— that you try to win. Are your games winnable?

I don’t think that’s a factor. I guess climax is a better term. I think win is a bit dominating. You wouldn’t say of a film, “Did they win?” I guess you could say was there a happy ending or not, but there’s a respect for non-happy endings as well in film. There can be a respect for games where you are not the victor. My games have a lot of different endings. They do have fairly triumphant endings. But I think some of them have pretty ambiguous endings. What do you think of the endings of my games?

There’s a dominant idea of alternative endings or a different set of choices. Like, you’re good or evil and you get a different ending. I found myself pondering over the end to “Howling Dogs” for a long while after.

Which one?

I don’t know! I think I’ve only had the same ending. You get up and then there’s one more phrase and then the quote at the end.

Is it the one with the leaves?

Maybe. I don’t know.

Is it the one where you wake up and get out of bed?

Yeah.

That’s the false ending. But it reinforces the real ending if you find it.