An oral history of watching the 1996 teen-witch movie The Craft

The Craft hit theaters in May 1996, summer blockbuster season. It was like many Hollywood youth movies of its time, the last teenage fin-de-siècle, only this one starred girl weirdos: sluts, cutters, orphans, white trash, and other marked bodies—a burn victim, a black girl. The Craft was a makeover movie, but more than the new-look montages, its makeover was spiritual.

Like all makeover movies, The Craft was about accessing power. From Funny Face to She’s All That, chick flicks have been teaching girls to wield power through good grooming and boys. The Craft offered an alternative point of access: through books, through nature, through one another. For girls who wanted more than boys’ attention—who wanted learning, money, independence, and maybe other girls’ attention—The Craft was a holy text.

Its heroine is Sarah (Robin Tunney), the new girl at a Catholic high school in suburban Los Angeles. On her first day, Sarah is befriended by three aspiring witches. These girls—Bonnie (Neve Campbell), Nancy (Fairuza Balk), and Rochelle (Rachel True)—are outcasts. They’re not bad students but impious: They worship a different deity, Manon (“Man invented God, this is older than that”). With the arrival of Sarah, a “natural witch,” the girls’ coven is complete. They start practicing magic, casting spells to right wrongs they feel have been done to them: back-burned Bonnie casts a spell of beauty; Sarah puts a love spell on a sleazy jock (Skeet Ulrich); Rochelle incants revenge against a racist, Marcia Brady–like bully; and Nancy, teen angst incarnate (poor, slut-shamed, abused by her alcoholic mother and leering stepfather), calls for all the power of Manon. At first, it’s all games and giggles, but then “the power starts to go to their heads,” and the good witch Sarah finds herself fighting against the evil of the other three.

An oral history of The Craft compels me because I’ve heard it already—in the whispers, Ouija magic, and love spells of inspired sleepovers. The Craft was a major pop phenomenon that trended, in a time before “online,” through clothes, books, and other RL rituals. For well over a year, from 1997–98, my First Avenue Public School in Ottawa was filled with little witches. I suspect that girls all over North America experience Craft-catalyzed “witch phases,” but the spell was atomized, the thousands of local histories held only in the minds of those who were bewitched.

Recently, I had a vision of a kind of Magic: The Gathering. I wanted to commune with the hemispheric coven. So I did my post-millennial research: I emailed, tweeted, and status-updated my way into the memories of friends and friends of friends. Seventeen years after its release, The Craft is coming of age. Here is its herstory.

If The Craft came out in ’96, I wouldn’t have been able to see it until the following year, when it came out on VHS. I would have been a 10-year-old and newly confirmed, following the rites of passage of the Catholic Church while simultaneously in the process of defecting. This was my time to create a separate personality from my parents and form my own thoughts and opinions. Watching movies they would disapprove of was the way to rebel. —Miranda King-Andrews, born 1987, raised in Ottawa

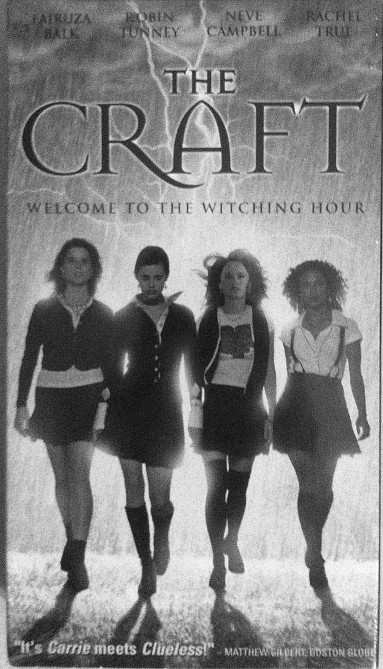

I, like most girls I knew, didn’t see the film until the next year, when my local video store’s new-release racks were decorated with handfuls of palm-size schoolgirls strutting in pleated skirts hemmed so short that, as my teacher Mme. Patridge used to say, “if you bend from the hips instead of the knees, you won’t be pleased.” I begged my parents to let me take them home. —Fiona Duncan, born 1987, raised in Montreal and Ottawa

I remember seeing the VHS box in the video store a million times before growing the balls to ask my parents if I could rent it. I remember that the front cover, with the four girls in schoolgirl outfits in a row, gave me that really particular tweeny feeling of being really confused by and attracted to sex and sexual bodies. —Tess Edmonson, born 1987, raised in Calgary

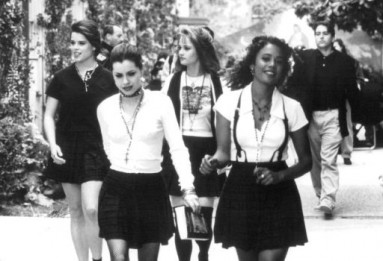

I can’t say when exactly I saw it, but when I did it affirmed what I expected: There are cool girls out there in the world with their grungy floral dresses, awesomely layered hair, cool sunglasses, being independent—all that shit I wished I could find for myself, but assumed wasn’t available to me. I was sure, though, like with this weird inordinate self-confidence, that eventually I would find all of it when I had left home. It also confirmed what I had already experienced and knew—that groups of girls, good or not, were evil. —Jackie Linton, b. 1985, raised in Kitchener, Ontario

The first time I saw The Craft, I was probably 9 or 10. I was at a sleepover birthday party with girls that were one or two years older than me, which at that age means so much. I remember two of the gifts the birthday girl received: one was a create-your-own-perfume set from the Gap in “Dream” scent and the other was one of those metal jeweled chokers that stretched somehow. I was very jealous of these gifts and also embarrassed about mine. This was generally the feeling I had about the whole evening and about The Craft: being just a little bit younger and less experienced than everyone, feeling excited but uncertain of myself, full of yearning, covetous of the fashion, yearning to fuck, all of that. —Rosa Aiello, born 1987, raised in Hamilton, Ontario

I remember watching The Craft on one of my first sleepovers ever with my neighborhood BFF back in Woodbridge land. We pretended we were the characters and stayed up well into the night afterward acting it out. We went to the library after that and read “spell books” like we were the only ones who knew they existed and pretended not even the librarian knew about them. She was probs a witch though too. —Lauren Festa, b. 1987, raised in Woodbridge, Ontario, and Salem, Massachusetts

The Craft hit my schoolyard like the Spice Girls and Sailor Moon, the latest thing. Wikipedia calls the movie a “sleeper hit”; I’d amend that to sleepover. That’s where we’d watch and rewatch the film’s 101 minutes. I had four best friends at the time, and just as we’d assign each other Spices or Sailors to play, we’d assign each other characters from The Craft. I was a Nancy—scrawny with a big chip on my shoulder. —Fiona Duncan

I did have friendships like in the movie, friendships based on being outcasts together or having one very specific thing in common. Friendships with girls like Nancy, who were usually justifiably warped by life and very mean, very into black-and-white concepts of justice, very unforgiving. I think that’s a relationship that most teenage girls have, with a tiny dictator who wants to direct the world as they see fit. And it’s appealing because then you don’t really have to think about anything, someone else can decide who you hate or like, where you’re going to direct your energy. I was always so consumed with doing the wrong thing that it was definitely a relief to have someone just tell me exactly who, where, and what I was supposed to be in order to be friends with her. —Haley Mlotek, born 1986, raised in North York, Ontario

Trampoline. Peacock Gap. 1999. I’m at my best friend’s house with another friend from middle school. There are three of us, maybe four. We want to be bad, we want to take some kind of risk that equals experience. But we only find ourselves in a rich suburb of San Francisco, in a house stocked with wholesome foods, and a beautiful garden backyard and hot tub. Our lives, in that moment, are not terribly dangerous. With a head full of The Craft and some implicit knowledge that we are weird outsiders, we decide, dramatically, to drink each other’s blood. (This, of course, being a recreation of the scene when Rochelle, Nancy, Sarah, and Bonnie take their “we are the weirdos” bus ride out into some pasture and drink each other’s pinpricks of blood in a magnificent goblet of underage red wine.) I remember it being kind of gross. We didn’t have wine, so my friends and I just watched how the blood coagulated in the water. It became something decidedly non-cinematic. But we sat on that trampoline and we tried to create a ritual that would bind us together in a way we couldn’t consciously guarantee, being 13, 14, not yet having entered high school, not yet knowing who we’d become. On the trampoline, I guess we wanted, in some way, to belong to each other. —Mary Borkowski, born 1986, raised in San Francisco

Trying to emulate the freedom and tenacity of the Craft women, we would set off on Saturdays and Sundays with a spell book and random artifacts to use: our parent’s wine, daggers, crystals, satchels, candles, matches. We were banking on windstorms and levitation, rising dead frogs, and moving things with our mind; after all, The Craft is a true story, right? So we stabbed a couple water beetles, chanted in circles under little cement underpasses, and every now and again someone would imagine that they levitated. Was it true? Potentially, sure? We all cut each other’s fingers, so I guess that means I have a lot of blood sisters, and we took vows with one another and the occult gods that have long since been broken and forgotten. —Monique Palma Whittaker, born 1986, raised in Guelph, Ontario

After watching the movie four times in a row, I tried to take some books on Wicca and the occult at the North Shore Library, the Lynn Valley branch. However, they were in the reference section and could not be signed out. So I just alternated between reading them crossed legged on the floor and sneaking to the Adult Fiction section to read sexy bits from VC Andrews novels. I became obsessed with “love spells” despite the hard lesson learned by Sarah, and have continued to seek them out. Everything from old Russian spells of putting a coin into a piece of bread and reading some poetry out loud to the Sicilian practice of mixing in some of your period blood in pasta sauce to charm a man. —Sofia Gassieva, born 1983, raised in Vancouver

I had two girl groups in my youth, both completely centered around being horny and having “seances.” The first group was called PTSCC (Preteen Sensation Club Club). In this club, you had to have read certain books and seen certain movies, including The Craft. You also had to own some form of bra, but we would happily construct a bra out of an old undershirt for any members too frightened to ask their mothers. We mostly played Ouija, drew on each others’ bodies, acted out very disturbing sex scenes with dolls, played with beads and candles, made slightly alcoholic drinks with cherry juice. Now that I’m answering these questions, I’m realizing that these girl groups coincided with my discovering masturbation for real, and with my first having serious sexual thoughts and urges, but those things are much too complex to trace. —Rosa Aiello

My long-lost friend Miranda (also a Fairuza) tells me that I served her red wine in my parents’ kitchen as a means of initiation in playtime cabal; I have no recollection of this. Listening to Miranda, I am hit with an image, a memory buried, of us and this girl Anna, the same cohort that would re-enact The Craft, playing a game we called “lesbians,” which involved rubbing up against each other fully clothed under the covers. —Fiona Duncan

My friend got this black magic book, and there was this one chapter that piqued my interest most. It was about spells cast with the male witch’s penis inside the woman witch’s vagina. You would sit and rock back and forth while saying the spell in unison until the cast was completed. Then something magical happened. I don’t recall what the spell was about, probably because I didn’t care and I would’ve wanted to know what boning felt like more than what a spell could do, so in a way The Craft led to my sexual curiosity. I began to see sex as a chemical equation; something that happened between two people which would result in new form of energy or existence. —Monique Palma Whittaker

I was a weird girl. I was the weird girl for most of my childhood. The thing I love the most about The Craft is that it’s about a group of girls who are leading very average, shitty, teenage girl lives, and they decide to do something about it. Why should a sixteen-year-old girl have to put up with a gross abusive step dad, or racism, or bad behavior from teenage boys, or feeling shitty about their bodies? This was a movie about girls who were experiencing very similar things as me and my friends, but instead of just waiting to grow out of it, these characters were doing something to make it better now. Instead of being ridiculed, they were feared; instead of being victims, they were sexual aggressors. —Haley Mlotek

Watching the movie again at 26, I realized I had blocked the second half of it from my memory, the part where the girls get drunk on power and are punished for it. I remember how uncomfortable I’d been with this turn since my very earliest viewings. I remember wishing I could perform some magic so that the film ended at the middle, in laughter, wealth, and sisterhood, instead of with white magic versus black magic. The lesson of The Craft should be like my favorite superhero Bildungsromans. But in ’90s Hollywood, girls didn’t get to be heroes. We could be enchanting, an object of dangerous allure, but never a subject who learns that with great power comes great responsibility. Given great power, we were taught we would fall. —Fiona Duncan

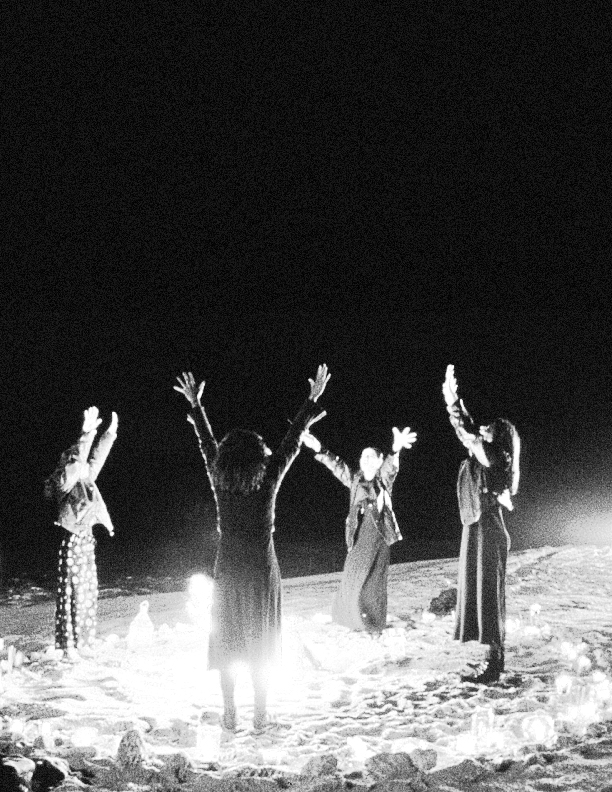

One of the scenes I find disquieting, disturbing, along with the entire second half of the film really, is the invocation scene on the beach, when each girl brings her specific contribution and prayer to Manon. The scene is violent and ugly in unexpected ways. There’s something ugly about each girl, under the guise of empowerment and some spiritual awakening, really just asking for some petty materialistic favor. It’s the climax and also the anticlimax: when things “go too far” and after getting drunk with the spirit they communally invoked, they wake up the next morning, sand in their mouths, sun beating down on them. The movie changes after that. —Mary Borkowski

When I watch The Craft now, the scenes I love the most are the ones where they’re enjoying magic. As a child, it didn’t really occur to how moralistic the whole story is—the girls are punished for experimenting with a force larger than themselves. I love the scenes where the magic is working for them, when they’re taking pleasure in the power they get from scaring other people instead of being ashamed of it. I wish there was another way to end a movie geared at teenagers that didn’t end with the girls seeing the error of their ways and going back to high school without powers, or locked up in a mental institution. Isn’t there some option in between the two? —Haley Mlotek

For me, The Craft represents a tonal existence that I wish I could settle into more often, even today. It’s dark yet elegant, it’s dark yet feminine, it’s dark but it’s fucking hot, and I feel like it makes my dark-sidedness a little bit more sexy. I like the power these women take back.

—Monique Palma Whittaker