A 15th century book shows the entanglement of architecture and appetite

ARCHITECTURE has a limited vocabulary for hunger. Predicated on sets of codes and reined in by fastidious discipline, associated with the avarice of urban development or the personified appetites of architects themselves, architecture at its root addresses a visceral wish not only for shelter but for threshold, mystery, and separation. Desire is a way of “negotiating the real,” as historian K. Michael Hays has written, and as the concretion of the real itself, architecture is less about built objects than lived experience. Desire in architecture is motivated not by lack—sterility, division and fear—but the excess and complexity of life and death. The ultimate modern hero, Baudelaire’s libidinal, feline flâneur, slinks through the Paris night, craving crowds and the “Babel d’escaliers et d’arcades.” The emergence of the modern city yielded a number of spatial pathologies—agoraphobia, claustrophobia—and new, nonlinear ways of mapping and traveling through the urban forest. The production and experience of the city are a two-way street.

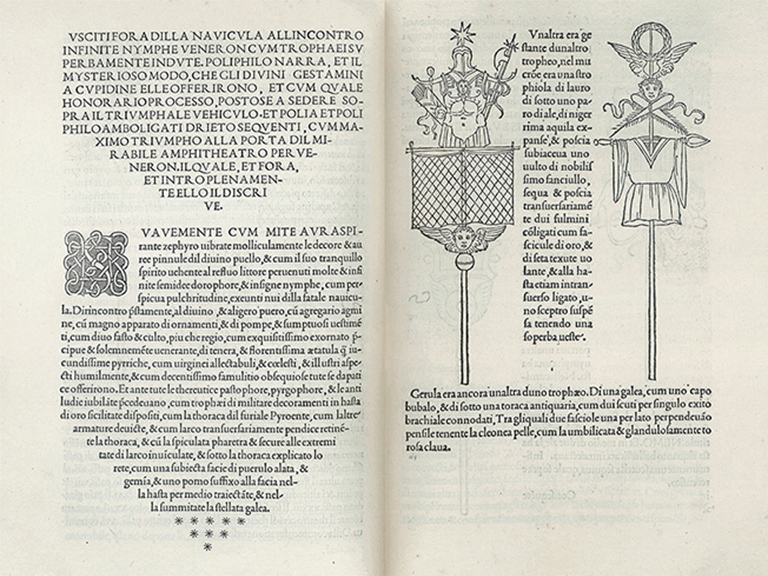

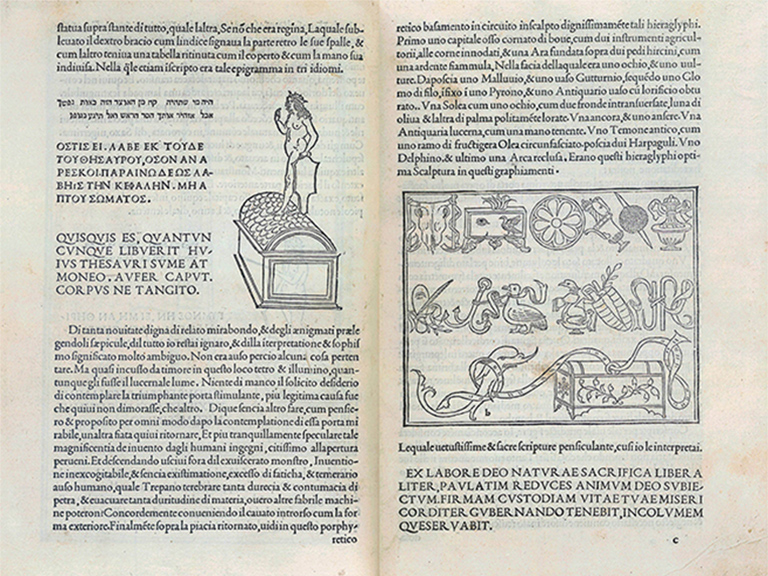

Some of these conditions far precede modernity. Ferociously messy, modern and haphazard, the mysterious Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (“the strife of love in a dream”), published in 1499, is in form alone one of the most radical books ever published and a manifestation of the High Renaissance appetite. If in the Middle Ages the body had been untrustworthy and contemptible, by the 15th century Eros had become a creative and civilizing force. The Hypnerotomachia was written in a volgare amalgam with smatterings of other languages, including Greek, Hebrew, and the first European appearance of Arabic. Illustrated by 172 ornate and delicate woodcuts, it is most famed for its erotic imagery—heavily inked over by the Vatican Library—but its depictions of ruin and landscape are almost as exuberant. The Hypnerotomachia at once repudiates the austere architectural treatise and is a precise, gemlike example of the modern book. It features a whole font family, including italics, but more fantastically, text flows around images and into shapes: spades, arrows, chalices. Attributed to many writers and illustrators, it usually bears the name of Venetian monk Francesco Colonna.

As polyglot pagan forest dreams go, it is notoriously difficult to translate. No full English translation was completed until 1999—the quincentennial of the book’s first appearance—by the musicologist Joscelyn Godwin, but it does not retain the original polyglot style. French translations—which appeared in the 16th century—not only retained much of the original style, but the woodcuts, in a more elaborate and refined French style, adjusted for perspective, contributed to the popularity of the text and were hugely influential on the dreams of Enlightenment architecture parlante: Anthony Vidler has suggested that the spherical chamber in the Hypnerotomachia influenced Etienne-Louis Boullée’s Cenotaph and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s Shelter for Rural Guards. In addition to Bernini’s elephantine Obelisco della Minerva, its influence is visible also in the Carceri, Piranesi’s fictional prisons and Bramante’s Belvedere Courtyard at the Vatican, but also Ashok Balhotra’s whimsical 1990s Kattenbroek neighborhood development in Utrecht.

While as a literary text the Hypnerotomachia has been dismissed as a silly Renaissance romance, it is also the most postmodern novel to appear until the 1920s, one of the world’s first graphic novels, a love epic, and an allegory of Platonic ideals. An atlas of fragment and alchemy and hieroglyphics, it is the strangest architectural treatise ever written, an ode to the polis not erupting from the forest but cemented in it. Four hundred years before psychoanalysis, the Hypnerotomachia dealt in the language of sleep and nighttime, seen not only as something sacred, but something to be feared.

The titular protagonist, Poliphilo—loving friend of “everything,” the city, and the beloved, Polia, with whom he is unacquainted—feverishly walks through a phantasmagoric forest of architecture and historical ruin, and falls asleep. Within this dream there is a second in which he travels through this dark forest again, facing a series of trials and riddles, embedded in the architecture with which he is obsessed, even fornicating with buildings themselves, one of whom responds ecstatically. Poliphilo feels “frenetic pleasure and cupidinous frenzy” at the sight of buildings, which give him “the highest carnal pleasure.”

The forms are depicted in immoderate detail—relics of the ancient world to the precise measurements within the architectural orders to feats of engineering—and distract him from finding the elusive Polia. Poliphilo, a bit of a hothouse orchid, is terrified by the journey. Early on, he is rescued by five nymphs, all of whom invite him to frolic and carouse in an extraordinary bathhouse before being permitted to meet with the queen, who presides over the Palace of Free Will. She provides him with a sumptuous banquet. In the garden he is faced with three doors: vita activa, vita contemplativa and the winner, the sinuous vita voluptaria. There he finds Polia, and they encounter several Petrarchan triumphal processions in their honor. Polia encourages Poliphilo’s exploration of architecture and the ancient world when he sees a mural depicting Hell and is terrified. They marry on the island of Cythera and receive yet another Petrarchan triumphal procession.

It’s all a bit too lucky for him: suddenly, in a Molly Bloom-style usurpation that occupies one-fifth of the book, Polia—hitherto silent—angrily informs the reader of what it is like to be the object of erotic fixation, rages against expectations of chastity, reveals her own carnality and rejects Poliphilo, who dies of heartache. When she kisses him, he is revived. Poliphilo tells his side. They are blessed by Venus. Finally, Poliphilo wakes up alone to the sound of the nightingale and shrugs; at least he still has architecture. He reasons away his disappointment:

I was left filled to the brim with a sweet and loquacious illusion…think how dark and dusky [it] would have been at this hour if I had really been enjoying the genuine and voluptuous delights of this lovely and divine maiden, this noble nymph!…I awoke and emerged with a start from my sweet dream, saying with a sigh: “Farewell, then, Polia.”

Hypereroticism drives the plot; Poliphilo desires building as much as body. Still most of his lust is directed at Polia—“sometimes it would come to pass that the wind would make her clothes flutter and uncover her legs that seemed to be made of scarlet, milk and music all mixed together”—but he is awake to the nymphs—in flesh and stone—and, unusually for books of the time, his fellow men. He swoons at the silken laces of delicate red shoes—“fine instruments for disturbing one’s life and for the excessive torment of a heart aflame!”—and takes great pleasure in displays of kissing—“juicy and tremulous tongues nourished with fragrant musk.”

INTEREST in the Hypnerotomachia surged after the book’s English translation. The Rule of Four, a Da Vinci Code–style thriller, saw great popular success. Liane Lefaivre published the hugely influential Leon Battista Alberti’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-Cognizing the Renaissance in 2005; in addition to a speculation about Alberti’s authorship—unlikely, given the book’s preperspectival drawing—it provides a great study of the text, especially as it relates to the phenomenology of the body. Le songe de Poliphile, a short film by Camille Henrot commissioned by the 2011 Paris-Delhi-Bombay exhibition at the Centre Pompidou—it appeared also in her 2014 retrospective at the New Museum—takes a more radical, dreamlike thread from the book, inspired by Jung’s reading and lengthy trip to India in the 1930s. The three stories within—a pilgrimage, pharmaceutical production, and milking snake venom—build in intensity as all separations dissolve.

The strangest reading, however, belongs to the architectural historian Alberto Pérez-Gómez, a 1992 book called Polyphilo, or the Dark Forest Revisited: An Erotic Epiphany of Architecture. If the original Hypnerotomachia was all about the lusty Renaissance appetite, Polyphilo is a warning tale of anorexia: architectural, emotional, sexual. The protagonist—the Anglicized/Russified “Polyphilo”—occupies not a sumptuous forest, but the air-conditioned non-places of the contemporary world, mostly in flight and at airports, at once frenetic and soulless. In 1992 Beijing had two subway lines and Dubai was a desert plain; one wonders what this text would be in the anti-spaces of the Internet. It has an extraordinary website: polyphilo.com.

Pérez-Gómez is a figurehead of architectural phenomenology and has been arguing since the early 1980s that the privileging of technology—in fact the visual—has led to a crisis of representation in modernity and loss of meaning in architecture. Polyphilo’s publication date is also important; the early 1990s were the beginning of Deleuzification throughout the discipline, which paralleled the development of parametricism throughout the decade. Among other things, the concept of the rhizome would liberate architectural discourse from some of its treelike constraints, like schemes of classification.

The Hypnerotomachia is often compared to Finnegan’s Wake, but Pérez-Gómez uses Ulysses as a formal paradigm in this “story of delay and fulfillment,” distilling the Hypnerotomachia into 24 chapters in about 18 hours. Much of Polyphilo is set in non-places, in flight or in airports; in addition to Boullée’s Cenotaph, Le Corbusier’s Convent of La Tourette and Gaudi’s Casa Batlló are found in the celestial shapes of the airspace and the planes of the new city. It takes on a similar didactic tone to the Hypnerotomachia, dreamlike, sexist and stilted, loaded with tautologies, and as well as—perhaps too successfully—the tone of its erotic content, “blunt and full of clichés;” it attempts a Rabelaisian journey through modern life, with flat tablets of fast food and the rush of white noise. Polyphilo cannot be judged by the standards of the novel or architectural text; much of the writing, in striving to be clinical, is simply unbearable, much in jest: “if I could slit axially your glimmering nylon cocoon with a single stroke of my X-Acto knife!”

Polyphilo’s humor seems to emerge from its fidelity to the text, so much so that its intent to convey that the meaning of architecture is like the knowledge of eros, learned on impulse through the body—not through aesthetic abstraction or functional logic—is lost; perhaps this is part of the game: “the curtain brings back longing. The indistinct image of Polya is imprinted on every crease and undulation of my body.” These are the erotic epiphanies of bodies without organs. Polyphilo lives in the “old capital,” founded on fratricidal blood like Sodom or Rome, which, at 60 degrees north, seems to be St. Petersburg. The citizens dress for the future climate and are able to comment on the refinement of each other’s intimate grooming. When Polyphilo wakes up feverish and alone and sees Polya for the first time, he remarks that her body is “clearly delineated,” inviting, even in fantasy, surgical care and precision:

An elastic vortex of insubstantial crystal projecting itself from her navel and surrounding me. Captured by the reflection on the surface, my vision continues for an instant, but my body is numb. The flesh is prevented from contact by the enveloping void. All my senses, except for vision, have been suspended and frozen in a different time.

Polyphilo observes the shape of the world at the airport, “manifestly capable of neutralizing erotic and criminal impulses, allowing only the material debris of sexuality, robbery and murder to exist.” Advertisements abound, and 20 years ago one could smoke in flight: “an odor of forced, pressurized oxygen and burning tobacco immediately saturates the cabin. I tumble into a state of abandon that almost leads me to renounce existence. In a fit of erotomania I am set by an uncontrollable vertigo, once more at the edge of the balcony.” Polyphilo, gazing at the “pigment of crushed snow crystals under the moon” as he listens to the airplanes’ metallic white noise, is mystified by the crush of technology, which once seemed so promising to him.

Most intriguing is the depiction of Polya, who, as in the Hypnerotomachia, hijacks the story. If the original was all milk and strawberries, Polya is an robotic, hyper-contemporary character raised between cultural extremes of the United States and North Korea, but is clearly from New York, extolling the Dutch tyrant Peter Stuyvesant. In her country, excessive emotion is “perceived as a degeneration of the primary functions of the neurorational system;” citizens of her country receive, through education, an invisible film on the epidermis that decreases sensitivity. She is consumed by work and religion and is taught: “a day has 86,420 seconds, that an ulva is a genus of seaweed, that little girls think about knives and blood, that women who are loved are in the grave,” and, when she grows up to become a “professional flyer”—flight being, for Perez-Gomez, a road to nowhere—so that she becomes impervious to physical desire. She is unable to understand gesture, emotions, or poetics. When she meets Polyphilo, she feels contaminated, irritated; her hostility depletes his life force, and he dies. After a horrific massacre in Polyphilo’s hometown, Polya wakes in the hospital. A nurse advises her:

Neither passivity, signs and tears, nor a domineering will to power would do. She emphasized that love is a kind of active feminine making, a compassion that lets things be, beyond the dualistic alternatives of action and passivity; an intuition deeply ingrained in the soul of women that would engender the unnamed order of the future in an act of creation that should invariably be implemented at the right and propitious time and place. She sent me on my way back to Polyphilo repeating for the last time that my vision and personal knowledge through love were indispensable to avoid the demise of the world.

Polyphilo—revived by Polya—writes her three letters imploring her to return. He tells her death is violent and ugly and nothing to extol. He writes twice more, from Greenland and Saskatchewan. They get together. There is a film of their story much like Last Year at Marienbad, which itself precedes the screening. The last chapter is a stage play—with three characters: The Lover, The World, and an “androgynous choir”—of pain and pleasure to be performed in real time in which the ending is almost like the original, except that the characters wake up to modernity and live happily ever after.

Pérez-Gómez has been criticized for a reactionary position on technology and meaning, but is not so far from the late 20th century anxieties of Barthelme, Pynchon, or Wallace about in the malignant, rhizomatic cloud of fecundity and violence that threatens modern life. Despite the introduction to Polyphilo which acknowledges the original text’s misogyny, Polya is an absurdly sexist character, a literal android leached by modern life, a late-capitalist ideal detached from the nubile Renaissance body and from decay. It is true that her lessons in becoming human are important; she may not be the original Polia, subverting the gaze to reclaim her identity from the heroic male Subject, but she is much more trapped in another person’s phallic journey, and one might wish for her a greater liberation than Polyphilo’s guidance.

Much architectural discourse longs for the Renaissance as if it contains within some lost Lacanian Thing. Manfredo Tafuri suggests the Renaissance is the site of an “original sin” in architecture that extends to a kind of mnemic mass destruction throughout contemporary art; he refers to a kind of spiritual nihilism which, in an attempt to obfuscate its way out of the nightmare of history only manages to anaesthetize its soul. There is no public lexicon of complexity and pleasure. The Hypnerotomachia not only transgressed the laws of its contemporaries but continues to warn against frigidity and tedium; its influence is also evident in the modern architectural storytelling of John Hejduk, Aldo Rossi and Madelon Vriesendorp. Bernard Tschumi’s 1976 essay “The Pleasure of Architecture”—written around the time of his Advertisements for Architecture, which now look like the provocations of any developer—distinguishes between eroticism as a subtle theoretical concept, discrete from blunt sexual allusions to skyscraper height and suggestive doorways; it is a voluptuousness that renounces conceptual isolation.

The imperial, colonial and propagandist objectification of building as tool of control contributes to the reification of architecture; divorced from the body, moral and aesthetic obligation, and even its role in the shaping of cultural memory, the built environment becomes merely an illustrative and instrumentalizing tool. Poliphilo, the ur-flâneur, living in a forest of ruin, counters with only this: Walk better; demand a braver and more expansive reading of the city than the anxious and linear one; think cool and live warm. His mythic dream of existential tourism is active and lucid: he acts on curiosity and is not presented with suggestive architecture, but hungers for everything he finds beautiful. The most sinister of structures creates its own mystery, casting shadows, creating threshold in the most forbidding places. It is a permission we give ourselves when we travel, to crumble and caress new textures as if we had no reference for them. The body adapts to the rhythm of its surroundings, and absorbs, in muscular memory and leftover dust, its character; the cities are our jungles, with all the accompanying cruelty and beauty, in shocks of smog and star.