The overlooked feminism of Ronnie James Dio

The late Ronnie James Dio is well-remembered for many things — his five-decade singing career; his choosing the Italian word for God as his stage name, his setting a benchmark for metal vocal power as a member of Rainbow and Black Sabbath; his propensity for slaying dragons during his stage show, despite his diminutive stature; his pioneering use of fantasy role-playing themes in his lyrics, spurring the development of the castle-rock genre; his fondness for magic and the spiritual symbology of rainbows — but the feminist undertones of his work are often overlooked.

Rob Sheffield claimed in his Rolling Stone obituary for the singer that "Dio barely ever sang about women unless he was empathizing with them," but even a cursory glance at Dio's canon yields counterexamples. Sheffield cites Dio's outspoken advocacy for the world's outcasts and underdogs to explain Dio's feminist empathy, but the case is not so straightforward as that. One cannot account for the purpose of such lyrics as "Don't smell the flowers, they're an evil drug to make you lose your mind / Don't dream of women 'cause they only bring you down" (from Holy Diver's "Don't Talk to Strangers") or dispel the overt phallicism of "Between the velvet lies, there's a truth that's hard as steel" (from the song "Holy Diver") without a more sophisticated hermeneutic.

Dio's feminism was not a matter of token acknowledgment of female perspectives, or extending his contempt for patriarchal religion, like the Catholicism he grew up with. Instead, galvanized by his struggles with chauvinistic guitar players whom he refused to let overshadow him, Dio developed a feminism that teased out elements of the killjoy temperament in metal's aggressive approach to its audience and put it to use in undermining masculinist structures of dominance at their ideological and psychical roots. "I'm trying to make these shouting statements for people,' he said in a 1994 interview with Joan Quinn, "shouting, screaming statements — we're angry about what's going on." But these were not overt, patronizing statements about gender issues; rather, they were Dio's attempts to enact resistance to patriarchy without being co-optive, without making a patriarch of himself. The peculiar absence of women from much of his lyrical universe speaks volumes of his refusal to speak for them, and also speaks to how feminism is not merely a woman's discourse about women's problems but an investigation of how difference inflects power and oppression.

In a 1985 interview with Amanda Redington, Dio explained his "mystical" lyrics as a palliative for "the awfulness in the world," which he pointedly characterizes in terms of rape culture: "Every time you pick up a newspaper someone's being murdered or being dragged behind a bush somewhere. And I think it's about time we use our imagination and live some of our dreams" — not the violent fantasies of male supremacy but measured vision of a universe where justice operates without the need for domination, as naturally and magically as the appearance of a rainbow.

1. "Lady Evil" by Rob Fellman

Ever since I was a little kid, I have consistently misheard one of the lines of the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman”: The first half of the stanza “she’ll rock you in the nighttime / ’til your skin turns red,” I heard as “she’ll lock you in a lantern...” Granted, it’s not a mishearing that would make it into a collection of funny mondegreens, but it had left me baffled for decades. As a six- (and twenty-six-, thirty-six-) year-old, I could make no sense of this line. How did you get locked in a lantern? Why, if, for heaven’s sake, you were to be put in one, would your skin turn red? And until your skin turns red? How long would that take?

It was only about a year ago that suddenly, cathartically, heard the line correctly, after 30 years and most likely hundreds of unintentional listens to the song — which speaks to its dubious ubiquity. (The Eagles’ Greatest Hits vol. 1 album was such a monstrous seller that the RIAA had to come up with “Diamond,” a designation above “Platinum,” to celebrate its sales figures.) It was cathartic because that little-child part of me that had all these years been terrified of this woman finally realized that this song wasn’t about a witch. It wasn't about someone who could magically imprison you in a lantern. It was about a woman that the narrator of the song — let’s call him Don Henley — had chosen to compare to a witch.

Let’s go to the tape. Young Henley has encountered a beautiful — one might even say bewitching — woman with “raven hair and ruby lips” who holds him “spellbound in the night.” She has led our hapless narrator to possibly some sort of commune dwelling, where he hears someone's — a roommate’s? lover’s? — sinister laughter “in another room” while she cooks up and gets high (“see how high she flies”), driving “herself to madness with a silver spoon.” Along with this apparent affinity for injectible drugs, this woman is depicted as a “restless spirit,” takes questionable lovers (“sleeping in the devil’s bed”), and might even be affiliated with a murderous criminal element (“someone’s underground”). And of course, she’s overwhelming in the sack: “She can rock you in the nighttime / ’til your skin turns red.” This suggests that sex with her is so hot that it literally scalds the skin, or perhaps more metaphorically, that it makes one into a debauched cartoon devil.

We’ve heard this all before. A tantalizing but transgressive woman is allegorized as a witch. Again. A woman takes a man outside his comfort zone—likely takes him to a place where his own disavowed wishes are on display—and so she must be condemned. So why bother with this song? Why talk about it at all? Because this song is fucking everywhere. Musically, it has some things to recommend it: a ceremonial, Gregorian-chant-meets-the-blues melody, fabulous 1970s doing-coke-off-the-mixing-board-while-reels-of-two-inch-tape-spin-slowly-in-the-background production, plenty of vocal parts for the car-based karaoke singer to sing along with, etc. etc. But this doesn't justify its omnipresence. I’d say that one (over)hears “Witchy Woman” more times per month than, say, one sees the portrait of the Mona Lisa, or the photo of Marilyn Monroe in her dress on the subway grate, or of many of the dozens of other iconic images of “womanhood” out there. Its relentlessness forces us, at least in part or on some level, to accept it uncritically. “Witchy Woman” holds pride of place in the idle talk of our time — that background of discourse that generates, maintains, and reinforces everyday average understanding.

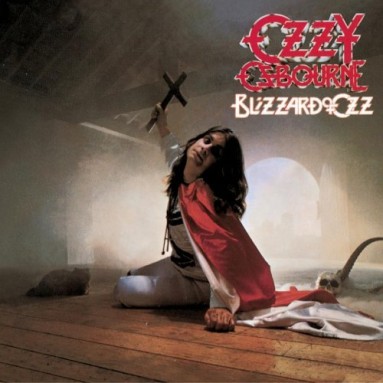

But there are altogether other ways of looking at the witch in the woman — ways that don't dully sublimate the widespread terrified male ambivalence in the face of the gendered other. Consider instead a song that got little or no airplay, “Lady Evil,” from Black Sabbath’s 1980 album Heaven and Hell, the first album from the Dio-fronted iteration of the band. The previous incarnation of Black Sabbath, with Ozzy Osbourne, didn't typically explore gender issues. "Evil Woman," from the band's first album (the U.K. pressing — the U.S. pressing mercifully replaced it with the far superior “Wicked World”), was a cover whose mostly perfunctory lyrics construe male lust as the result of female provocation; "Paranoid" essentially forswears women altogether because they "couldn't help me with my mind." And Technical Ecstasy's "Dirty Women" is a paean to street-walking prostitutes who "don't mess around" — the cash nexus resolves them of any game-playing or witchery.

“Lady Evil” offers a wholly different take on the witch, one with roots in Dio's sojourn in Ritchie Blackmore's Rainbow. The template for "Lady Evil" can be found in "Starstruck," on Rainbow's 1976 album Rising, which invokes a groupie with supernatural powers, who can fly to the moon and "creep like a hungry cat" in pursuing the singer. “Lady Evil,” however, strips the explanatory context and offers a plotless portrait, much like Henley's "Witchy Woman" — that represents female evil as inherently incarnate. In "Lady Evil," Dio inflates the muted inexplicability of Henley's witch and invokes a genuinely supernatural creature — a “magical, mystical woman.” She has tamed “the darkness,” which “eats right from her hand.” She can “freeze you where you stand” with a banshee’s wail. She’s the “queen of the night.” She can befuddle you: she “takes your vision and turns it all around.” Dio also smuggles in a bit of a brag, claiming Lady Evil is a “lady I know” and vicariously enjoying some of her potency. But on the whole, he is advising the listener to stay the hell away from her, not because she is schemer or a heartbreaker but because she is unambiguously and inexplicably malign.

All this would be unremarkable D&D persiflage — admittedly, from a master of the form — if not for the song’s opening line. After a few measures of threatening bass chug and period-appropriate guitar vamping, Dio sets the scene by yowling, “There’s a place just south of Witches’ Valley.” This is intended to be the opening line of a dark fairy tale, but it sounds more like how someone would begin giving you directions to a new winery. (Just south of Witches’ Valley? Presumably Witches Valley proper is too trendy.) That brilliantly ham-fisted opening line obliges you to hear the rest of the song's lyrics in an absurd register. It compels you to recognize that there is something equally ridiculous in a man calling a woman a witch. By saying “ridiculous,” I don’t mean to efface the thousands of years of murderous terroristic traumatic misogyny — of which the periodic witch hunts of yore are but one example. I mean to suggest that one of the ways to combat this misogyny is to mock the act of perpetuating it. Dio is saying: Aren’t I ridiculous for singing this? Isn’t this song absurd? This forecloses the sublimations of terrified misogyny and foregrounds their failure.

(In this regard, a predecessor to “Lady Evil,” albeit one without supernatural allusions, is Dion’s “Runaround Sue.” This is ostensibly yet another song shaming a woman for her sexual agency, but the singer’s ebullience as he sings the joyous whoop of the chorus conveying his cuckoldry — “she goooooes / out with other guys!” — offloads his sexual frustration and narcissistic injury onto the listener. We’re stuck with feeling censorious of Sue; we must process Dion’s shame for him while witnessing his dissociated cheery affect. But with the slightest amount of criticality, we understand that to succumb to projective identification via this pop-music trifle is patently ridiculous, and so the entire intersubjective psychic structure the song tries to construct collapses under its own absurdity. Dion is incapable of containing and metabolizing his own feelings regarding Runaround Sue, so he must project them into his listener, who with little effort can laugh off his attempt, and Dion ultimately is left as nothing but a saccharine doo-wop shell.)

This ironization extends beyond the boundaries of "Lady Evil," casting a retroactive spell over all the rock songs about witchy women. Once you have learned the lesson of “Lady Evil,” you can no longer hear a song like “Witchy Woman” without a reflexive and critical awareness of its casual misogyny. It ceases to be part of the idle talk of our everydayness. The banality of the sexism emerges from the background: how silly it is to point to a woman who has wounded your male pride and call her a witch! Santana sounds like a petulant toddler for grousing about his girlfriend’s “Evil Ways” because she dares to have a social life apart from his. Spooky Tooth’s singer raves about an “Evil Woman” because she had the temerity to break up with him; this is the milquetoast burble of impotent narcissistic rage. The same goes for Jeff Lynne’s “Evil Woman” (she’s embarrassed him), the Doobie Brothers’ “Evil Woman” (she’s sold him drugs), and Sir Lord Baltimore’s “(Woman Is a) Hell Hound” (she arouses him/she might have given him VD).

It turns out you just can’t get away with calling a woman a witch, unless, perhaps, you’re just south of Witches’ Valley.

2. "Kill the King" by Rob Horning

Dio was deeply enamored with the idea of populist uprising. The theme crops up in one of the earliest interviews he gave as a member of Rainbow — in 1975 he described "Sixteenth Century Greensleeves" as being about a "village living in squalor," whose peasants revolt against the "black knight" for exercising his seigneurial privilege by abducting and presumably raping a girl. (The song's lyrics detail how the king rather than the virgin will be "undone": "It's only been an hour / Since he locked her in the tower / The time has come / He must be undone by the morning.") Decades later, touring with his namesake band, Dio talked about his trademark stage routine of dragon-fighting in similar terms. "The dragon is meant to be just an example of the injustices that people will put up with until they rise up and say, Hey, I've had enough of this crap from you ... A lord of the manor or a king who was a very evil evil person, and eventually the peasants rise up against him and kill him, there is another dragon gone."

This regicidal sentiment is expressed most bluntly in song in "Kill the King," from the 1978 Rainbow album Long Live Rock 'N' Roll. Here Dio expresses most succinctly his theory of revolution and his sense of the potential risks beyond the immediate satisfaction of epistemic disruption. Its opening lines immediately define the stakes of the revolt: no mere populist revolution but an assault on the fundamental basis of patriarchal society, on not just the king as head of state but as representative of the law of the father and the metaphysical basis for a phallocentric organization of social meaning:. "Danger, danger — the Queen's about to kill / there's a stranger, stranger life about to spill." If meaning must be anchored to a transcendent signifier of which a king would be the paradigmatic example, this female assault on the principles of logic would certainly estrange the wor(l)d, rendering life no longer livable according to the old dichotomies that previously reigned. "Power, power / It happens every day," Dio sings, only now, freed from its patriarchal containment, "power" will "devour all along the way."

Clément and Cixous pose this question in The Newly Born Woman (1975): "What would happen to logocentrism, to the great philosophical systems, to the order of the world in general if the rock upon which they had founded this church should crumble? If some fine day it suddenly came out that the logocentric plan had always, inadmissibly, been to create a foundation for (to found and fund) phallocentrism, to guarantee a masculine order a rationale equal to history itself." Without the King, without the rationale his enthronement guarantees, power courses though the social body in completely unpredictable circuits, in an unprecedented, "nonhistorical" fashion. The singer calls for a "spell or a charm" to contain the violence to the symbolic order, to both exempt himself from any reconstruction of a phallic order ("I'm no pawn, be gone") and to protect himself from the psychic annihilation inflicted by the unbounded Real.

The desire for fantasy to subvert, if not supplant, the customary operation of power would prove a persistent theme in Dio's music, surfacing even in his most influential song, "Rainbow in the Dark," where he will "cry out for magic" to arrest the dissolving of subjectivity, the sense that he is a "lie," that we can become "words without a rhyme." It's hard not to see in this yearning for magic an invocation of a primordial feminine principle beyond its definition within patriarchal codes, which have traditionally used it to underwrite modes of domination and subordination, "to blind your eyes and steal your dreams," as he puts it in "Heaven and Hell." Only through the "treason" of fantasy – to return to the language of "Kill the King" — can power be suspended, can the obscene image of a king without a head become tenable, viable.

Dio's unwavering sincerity with respect to the liberatory possibility of fantasy should not blind us to its richer affective potential. If he is rigid in his seeming lack of ironic distance, it may be because he seeks to present himself as a sacrificial emblem of the phallic power he would have listeners decapitate. In other words, he remains solemnly serious so that we can have a target for the magical force of mirth. In The Sex That Is Not One, Luce Irigaray points out that "there is no simple manageable way to leap to the outside of phallologocentrism," and explains that "if I was attempting to move back through the 'masculine' imaginary, that is, our cultural imaginary, it is because that move imposed itself, both in order to demarcate the possible 'outside' of this imaginary and to allow me to situate myself with respect to it as a woman, implicated in it." As a man, Dio's attempt at a leap is even more fraught, and requires an equally risky strategy of privilege destruction. He invites laughter with his seriousness; makes fantasy possible with his grim determination. "Isn't laughter the first form of liberation form a secular oppression?" Irigaray asks. "Isn't the phallic tantamount to the seriousness of meaning?"

When Dio invites us to "kill the king," he knows he must willingly lay himself on the guillotine of ridicule, to ensure that we "escape from a pure and simple reversal of the masculine position," as Irigaray explains. The king is dead. Long live rock n' roll.

3. "Tarot Woman" by Karen Gregory

I grew up scared of Ronnie James Dio. I thought he was the devil, or a least a demonic incarnation. Dio and his music were strictly forbidden by my mother, who converted to a form of Charismatic Christianity when I was in the sixth grade. Having met “an angel” — a woman named Mary who walked into my mother’s bridal shop and said something along the lines of “I had a feeling you needed me” — my mother embraced Jesus with a passion that, at times, scared me more than the devils she was continually warding off.

For several years, at the height of my adolescence, my mother transformed our decidedly unenchanted suburban Massachusetts house into a shrine to the fight between “good” and “evil,” between Jesus and the Devil, and between teenagers and rock and roll. Before my mother met her angel, she and I had actually bonded over horror movies, the occasional Ouija board séance, and scaring ourselves with ghost stories. Yet over the course of a few years, crucifixes, holy relics, Virgin Mary statues, chalk markings to ward off evil spirits, little bottles of holy water, and small, plastic laminated prayer cards slowly came to replace those pastimes. As the house became more “spirit filled,” more and more elements of American culture became intolerable to my mother.

In attempt to protect us or ward off evil influences, my mother’s persistent intercessions and prayers, often in the form of the “laying on of hands,” actually made the Devil and his minions commonplace companions in my pre-teenage years. The world, particularly the world of mass media and culture, became a lens through which to see “evidence of Satan in the modern world.”

(This is the title of a book was on our living room bookshelf for years and never failed to intrigue me. Evidence? Satan? Well, if there is “proof” he must exist, reasoned my adolescent self.)

I can still remember the day that my mother spontaneously canceled our family’s cable subscription to save us from MTV. Though my two brothers and I had camped out overnight to be prepared to watch MTV’s inaugural day — we couldn’t believe it: Music! On television! — my mother feared that bands such as Black Sabbath and Dio were the devil’s own emissaries, capable of stealing our souls. Of course, no matter how much she tried to keep out the dark forces, they crept back in through the radio, friends, and contraband records that my brothers smuggled into the house.

When you think the world is populated by demons, you tend to see proof of their existence in even the most ordinary objects, and the world can become a topsy-turvy world of shifting perceptions. I remember trying to perceive or “discern” the presence of evil in song lyrics like Black Sabbath’s “Heaven and Hell”

And they'll tell you black is really white

The moon is just the sun at night

And when you walk in golden halls

you get to keep the gold that falls

It's Heaven and Hell, oh no!

Fool, fool!You've got to bleed for the dancer!

Fool, fool!

While the “moon is just the sun at night” was downright confusing to me, “bleeding for the dancer” was actually a little terrifying. Combined with the cover of Blizzard of Ozz, which I would regularly sneak out of its hiding place among my brother’s records and contemplate, wondering if Ozzy really ate live bats on stage, I gave in to worry that somehow these songs and images could really operate as portals, releasing untold — and often unseen until it was too late — demons.

At the height of my mother’s conversion, she and I would spend hour discussing “signs” of the presence of evil. After taking me with her to a “prayer circle,” where (mostly) middle-aged white women sat in folding chairs in the basement of a church, my mother confessed to me that during her experience of deep prayer, she saw the face of demon emerge from the basement’s carpeting. I was truly horrified at this development in my mother’s — and by extension my own — perception of reality. "Don’t fear," though, was always her advice, because the answer to any demon is always more prayer, to condemn its evil and to steel yourself in “the blood of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

In the depth of the night, I would sometimes lay awake in bed praying with all my heart that I would be fully “covered” in that protective blood. Hearing common sounds of the neighborhood, I would be convinced it was the Devil coming to finally make his appearance known to me. While my mother seemed to grow more confirmed in her powers of demonic perception, my middle-school years were a persistent lesson is learning to un-trust my self and suspect even the simplest objects as potential sites of possession.

At one point, in an earnest attempt to protect my friend, I told her that the little owl figurine on her dresser was a “bad” omen. Needless to say, the friend cried, her mother interrogated me, and I was sent home having probably both angered the family and creeped them out.

Therefore, when many of my suburban friends went through a metal music phase, my ever-vigilant mother pronounced both my friends and the music to be the devil’s little minions. Dio was truly a devil, with his flagrant “devil horn” hand gestures that he is often given credit for inventing. Judas Priest was certainly attempting to brainwash us with their diabolical ways and by the time they went on trial in 1990, charged with the insertion of subliminal messages into their music that prosecutors attempted to link to the self-inflicted deaths of two young men in Nevada, my mother was fully indoctrinated into the Satanic panic that had been sweeping the country. My brother’s contraband Led Zeppelin records were even sniffed out by my mother and played backward for the entire family. Her rock-and-roll witch hunt pervaded our home to the extent that one of my brothers hid a 45 of Huey Lewis’s “I Want a New Drug” in a cabinet in the basement from fear that the word drug would provoke the Inquisition.

It was only years later, when I left for college, that I was able to gain some distance from my mother’s metaphysical abuse. I returned home one summer and openly read my copy of The Mists of Avalon as a test of her power. Maybe she didn’t really understand what I was reading, but it was, for me, a turning point in our relationship.

Still, dropping the veil of a decade of Charismatic Christianity, however, didn’t happen for me overnight. As college friends introduced me to rather commonplace New Age practices, astrology, and Tarot cards, the guilt of “dabbling” in the Devil’s work haunted me, and I felt my world and my mother’s work were becoming ever more incompatible. Tarot, in particular, became for me a site of connecting with other women and of talking through our lives and its possibilities. Yet I never dared to show my mother a pack of cards. At the same time, the music of my middle-school years began cycling back into my life, taking on the kind of cultural capital of “referencing” songs from the late 1970s and early 1980s. Dio, in particular, took on a kind of role as muse to revisiting a lost memory of Massachusetts.

And, it was, then, with a tinge of sadness that I learned Dio had learned to make his famous “devil horns” gesture from his Italian grandmother. As Dio explains in the documentary Metal: A Headbanger's Journey, both his maternal and paternal grandparents immigrated to America from Italy, carrying with them “superstitions.” As a child, Dio would be waking with one of his grandmothers when she would suddenly extend her forefinger and pinky, making the sign of the “malocchio” or the “evil eye.” The hand gesture can be used either to ward off the “evil eye” or another or to curse. Dio claims to have “perfected” and made the gesture important to metal fans. To me, it seemed that such easily transmitted maternal folkways and “witchery” had been distinctly severed from my inheritance.

Years later, when I traveled to Galicia, the site of the last legal witch burning in Spain, to meet my husband's grandparents and learn of the still living folkways of brujas and meigas, or white witches, and nature rituals like jumping through a bonfire on midsummer’s night and the making of queimada, a flaming punch of aguardiente (basically a Galician grappa) to keep away evil, it dawned on me that my Portuguese mother’s conversion had foreclosed forever the passage of such ways or knowledge from any my older ancestors, particularly my grandmother and great-grandmother who had immigrated to the U.S. from Portugal.

Today, I work with esoteric and spiritual practitioners in my own academic work, but in many ways my work is an attempt to learn to trust myself. It turns out the greatest trick the devil ever played is not that he convinced the world he didn’t exist but the idea that the world should be understood as a terrifying place. And, I think I have finally found a kindred soul in Ronnie James Dio—a man struggling in his own ways to throw off the oppressions of the Catholic Church and its overwhelmingly violent forms of authority and patriarchy. Dio’s struggle resulted in a world of not only demons but rainbows. (But not rainbow demons. That’s Uriah Heep.)