Social media puts an end to shyness by generalizing its pathology

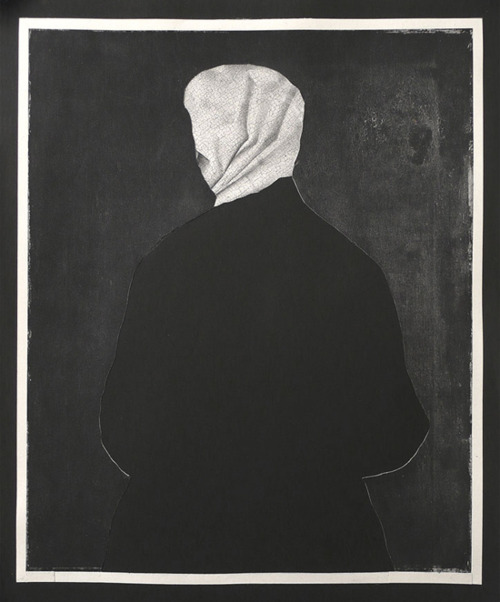

As a shy person, I’ve believed for most of my life that being among new people required an elaborate social disguise, one that would allow me to feel both present and absent, noticed and unnoticed. I’d yearn for some sort of social recognition without the bother of having to be recognized, without that oppressive pressure to live up to anything that might get me attention in the first place. So I’d find myself executing oblique tactics — being stingy and stealthy with eye contact; wearing a mask of deep concentration; staring at an underappreciated object in the room, like a light fixture or molding — in hopes of discouraging people from engaging me in actual conversation while still conveying the impression that I might be interesting to talk to.

The problem with polite conversation, I thought, was that it required the orderly recitation of platitudes before one can say anything interesting, let alone something as original and insightful as I wanted to believe myself to be. I couldn’t bear it. I had an irrational expectation that people should already know what I was about and come to me with suitable topics to draw me out. Rather than attempt agreeable chitchat and compromise my “authentic” identity with false congeniality, I would isolate myself, hoping that withdrawal would make me come across at a glance as mysterious and different rather than rude and feckless. If I had to volunteer talk about my tastes, interests and opinions out of context, they might be exposed as somehow wrong or worse, as not especially distinctive. And even if I hit it off with someone, my ineffable singularity could have easily vanished in the consensus of compatibility. I’d rather my self-importance remain undisturbed by anyone’s curiosity about me than risk seeming ordinary to myself.

This gave me my basic framework about how to behave in social situations. The possibility of discovering genuine connection with other people receded to fantasy; I could only try to make it through without embarrassing myself. Shyness had made me so deficient in empathic experience that I could only view social life in terms of risk rather than opportunity. The best way to manage that risk, I thought, was to be unapproachable but legibly fascinating at a distance, to present myself as an object to be read but with a message that’s inscrutable and fleeting, one that could convey the complexity of the real me without reducing it to something superficial. I could not get past the wish to broadcast my identity without having to interact with anyone.

Facebook, of course, caters to that desire. Because its business model relies on user-generated content and the data-mining it makes possible, Facebook is engineered to facilitate “sharing.” It frees users to build an identity in isolation, unhampered by contingencies of face-to-face interaction or real-time reciprocity. Or in other words, it allows socially anxious people like me to assemble a shyness disguise that others appear willing to accept as genuine. A 2010 study, “Shyness and Online Social Networking Services,” by Marquette University psychologists Levi Baker and Debra Oswald, confirms the social network’s potential to mitigate shyness, finding “immediate benefits of Facebook use, especially for shy individuals, as it allows social interaction in a comfortable context.” They suggest that “computer-mediated communication” allows shy people to escape the complexities of face-to-face interaction that they typically struggle with: the discouraging pressure to come up with conversation topics, the nonverbal cues that can confuse them, the rituals of etiquette that calibrate intimacy.

With Facebook, shy people experience greater control over self-presentation at a pace they can handle. Users can manage the flow of social interaction, experiencing social life through a dashboard and time-shifting friendship to suit their needs. On Facebook, no one need worry about volunteering information clumsily or at the wrong time, or expressing enthusiasm with a little too much energy. You don’t have to worry about interrupting anyone or expect to be interrupted. You can’t misjudge the moment, because social media suspends spontaneity.

Naturally, this removes inhibitions, as urges to share and respond aren’t disciplined or evoked organically by the particularities of any given moment. Thus, it wouldn’t seem that weird to anyone if I went on Facebook and commented randomly on friends’ old photos before blurting out that I’m in a Wawa buying a hoagie and listening to an early Genesis album, which I might supplement with links to ever-more obscure YouTube videos. Such self-revelation no longer requires an occasion, something shy people are generally incapable of creating for themselves.

Citing earlier studies, Baker and Oswald note that shy people “received less advice and guidance, felt less close and connected, received fewer assurances of worth, less support, and felt less assurance that they could count on others” because they tend to avoid social situations. Facebook abolishes situations and replaces them with persistent and legible networks from which the fruits of friendship can be extracted. Thus in Baker and Oswald’s study, shy Facebook users report experiencing “increased friendship quality” and “increased social support” from their Facebook friends.

But what allows shy people to grasp that increase is the way social media make friendship concretely quantifiable. Social media don’t merely insulate shy people from shame and suppress social risk; they routinize sharing and automate camaraderie, giving them standardized forms. On Facebook, the tokens of friendship and the gambits of personal affectation are expressed in the same currency, a kind of proxy for conventional attention, and circulate in the same economy of affirmation and ostentation, as Likes and updates and comments. The fleeting pleasures of sociality are objectified and rendered static, consumable, explicitly useful. They can be exchanged asynchronously or piled up in reserve to ameliorate occasional outbreaks of acute anomie. In real time and space, you can’t explicitly keep track of how often someone looks at you or answers your questions or has a positive thought about the way you have presented yourself, but within Facebook, you can. In this way, it inverts attention’s scarcity: At social gatherings, there’s not enough to go around for those who don’t put themselves forward, but on Facebook we are sovereign masters of a digitized hoard of attention.

By supplying a measurable currency of friendship, Facebook offers the shy and non-shy alike a kind of social-capital management system. It seduces with the allure of metrics, the thrill of measuring one’s reach the way a marketer would — how many hits you get, what kind of demographic you are drawing, how successful you are at getting target audiences to interact with you, what you need to say, what you need to reference, or how much skin you have to show to attract more attention. It reconceptualizes the costs of shyness, translating it into a calculable number of missed opportunities for fruitful exchange. This offers shy people a more direct way of measuring lost social capital and straightforward procedures for compensating. It doesn’t require nebulous acts of consideration, risky gestures of sympathy, or intuitive leaps of understanding. Instead, it takes nothing more than an assiduous narcissism, a diligence about reinforcing one’s online presence and monitoring the returns.

So while Facebook can aid in the pursuit of social capital, it doesn’t seem to alleviate the psychological hang-ups that produce shyness in the first place. Facebook doesn’t attempt to solve the shy person’s fear of social presence; one remains free from the obligation to reciprocate in real time; one preserves a safe distance from any potential audience by broadcasting at them rather than interacting with them. It caters to an appetite for attention on demand, administering the illusion that an audience’s sincere ego-sustaining interest can be automatically inferred from our continual participation. By improving users’ levels of social capital, it offers a more stable rationalization for the shy person’s behaviors of avoidance, and by offering mechanisms to control social presence at a distance, it may actually exacerbate the selfishness of shyness and reinscribe solipsism. Instead of having to reveal oneself, with all the vulnerability that implies, one can calculate self-presentation much more deliberately in social media. This sustains the idea that personal identity is a purely individualistic proposition — that it is not formed through social interaction but prior to it, in isolation.

Rather than eradicate shyness, Facebook seems to generalize its pathology to all its users. In this, it serves a broader project of institutionalizing a kind of subjectivity suitable to neoliberalism, that is, to socioeconomic conditions of pervasive risk in which isolated individuals are expected to be perpetually flexible, unattached to any particular identity, and willing to bear much more responsibility for coping with instability. Whereas it was once plausible to talk of orderly and predictable stages and roles in one’s life, economic destabilization has rendered such a course unlikely for most people. Instead, most face precarity — economic insecurity as a structured and permanent component of life rather than a temporary anomaly. Because work conditions are subject to change without notice and work itself is not guaranteed, the distinction between work and nonwork blurs. One must adopt an entrepreneurial attitude toward the business of life, identifying opportunities whenever they come and cultivating resources to replace what was once offered for merely adhering to the standard life pattern.

The shy person’s fear of social failure once seemed disproportionate to what was actually at stake ; it seemed a strictly personal matter with few economic ramifications. But now they shy person’s apprehension of social risk seems entirely rational, as who you know and what they are willing to do for you may be the key to one’s economic survival. Social capital has never been so important, seeming to dwarf the significance of the unexploitable aspects of friendship. This is a reason more and more social interaction registers as inconvenience. Social media allows us to feel we can draw on a huge wealth of information while participating in social life at our own convenience, controlling it to our advantage as a way of managing risk without having to make any compromises or sacrifices to partake in a community, which recedes as a utopian ideal.

Older media forms once offered vicarious entertainment in exchange for our passivity. We could escape from ourselves by projecting into fictional worlds designed to welcome us and to reinforce our sense of the rightness of the roles tradition forced upon us. The refuge for the shy person, beyond the illusion that entertainment addresses us directly and renders us less alone, was in the rigidity and pervasiveness of such standards. One could disappear into conformity, unthreatened by the sense that everyone else was leading a more exceptional life. But now traditional roles have been discarded, and individuals are instead expected to develop original lifestyles, aspects of which can be appropriated to drive an economy that increasingly relies on stylistic innovations for growth. Social media is at once the field in which these lifestyles are deployed and where they harvested for economic advantage as marketing information. Facebook demands interactivity and does not tolerate passivity. It promises not escape from the self but immersion in it. Under such circumstances, when total self-involvement serves as a perfect substitute for gregariousness, shyness becomes irrelevant. Eventually, it will become nostalgic.