In Chris Abani's new novel The Secret History of Las Vegas, universality is in the particular and nothing stays where it's supposed to

“This hands cannot do. Even interlaced across a pregnant woman’s stomach, even if the will that webs the fingers desires nothing more than to protect the unborn in her—not even this is sufficient…” Hands cannot protect her or the fetus in her womb from the effects of a nuclear test blast; cannot protect her or her fetus from the bright flash become a cloud, become a “thick tree with a dense plume.” Despite her desire to protect, neither Selah, the woman who webs her hands, nor her fetus are protected. Desire is not enough. But Selah loves her sons, conjoined twins named Fire and Water, and she knows the country in which she lives (one that conducts nuclear blasts in civilian areas) and she has refused to submit them again to the army—this time to the doctors on the base whom she is told have the ability to perform the surgery that would separate them. “The idea of it, an unspeakable insult, that those who did this should be begged to undo it, curdled the milk in her.”

Before she ends her suffering by hanging herself from the branches of a bristlecone pine, Selah—whose name is as anagram for heals, a Hebrew word that marks a pause in the psalm (like an Amen, a moment to mark and to consider the music), and the root word for weight or hang

She is. And she’s not the only one.

In one way or another, everyone is fucked in Chris Abani’s noir-ish novel The Secret History of Las Vegas. As one might expect from the author of Graceland and The Virgin of Flames, Abani’s latest is not an ordinary crime novel, but it plays with a set of familiar narrative forms: a set of connected stories of people on the run from their pasts and presents, a detective trying to clear up a series of unsolved murders, and a deep interest in mapping desire and desire’s failures. Racism and heartbreak curtail the lives of everyone in this novel, from Selah’s parents (her father is murdered because through the eyes of the sheriff of the town of Gabriel, a black man filling a pipe with tobacco becomes a black man with a gun, and her mother dies of heartbreak shortly after) to Selah herself, the woman who would protect her children but can’t, to Dr. Sunil Singh, his lover Asia, and his nemesis Eskia who was active in Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s armed wing.

“Vegas,” Singh thinks, “is really an African city.” And what happens in Vegas doesn’t stay there or begin there. Taking place over the course of four days (Friday through Tuesday), many years, and 60 tight chapters, The Secret History of Las Vegas explodes geography and genre – the places and the crimes of this novel (its secret histories) are measured in bristlecone pine time, global historical time. And whether a character is from South Africa or the Southern U.S. all of them are fighting past and present demons as space and time collapse into each other and repeat.

One of the secrets at the heart of this novel is the (hidden) history of those black people who have lived, struggled, and made their homes in Las Vegas. These are not the black performers of the past who came to town for shows at venues where they were not welcome in the audience, in hotels with pools they could not swim in. At the center of this book are those black people and their descendants who made their homes in Las Vegas after migrating from the Jim Crow South and who populated a 3.5 square mile portion of the segregated city’s Westside. The majority of the primary and secondary characters in the novel are black, and those who are not from Las Vegas have run there as they flee something and somewhere else.

As I read the novel I wondered for whom this blackness is visible, because many readers of fiction readers assume a character’s whiteness until (and sometimes even after) she is described otherwise. I wondered to and for whom this blackness matters. Blackness’s in/visibility has profound implications for the particularities of the narrative’s unfolding and its very human heart. Abani doesn’t engage in what Frank Wilderson calls the “ruse of analogy”: the violence of universalizing black suffering as one is called to enter into and inhabit a particular narrative world. All of Abani’s characters are enmeshed in a web of specific histories that cannot be reduced to a common story of universal trauma but that nevertheless speak to and past their particularities. The novel’s stories of failure, revenge, and reparation show us how the universal is always particular. From the two-year-old case of a murdered teenage girl that Detective Salazar has yet to solve, to the struggles of the Downwinder nationalists, to Sunil’s unrequited and rejected loves: the sex worker Asia with whom he is “in love,” former lover Jan Krige whom he helps break at Vlakplaas, and Dr. Sheila Jackson his colleague at the Desert Palms Institute who dresses like Pat Benatar. As Jacqueline Rose has taught us, “One way to come at the concept of universality might be to note, on each separate occasion, the history which provokes it.’’

Dr. Sunil Singh is a black South African

There is no escape, even if there were a cure. Sunil’s relocation to Las Vegas and Desert Palms finds him doing Army funded research, “part psychological, part chemical,” in which he studies the “causes of psychopathic and other violent behavior with the aim of harnessing and controlling that behavior. To turn it on and off at will, as it were, with a serum or a drug of some kind.” Sunil imagines the work to be reparative and redemptive, but his boss Brewster refuses his attempts to step outside of a brutal history and its presents: “‘There’s a reason only the U.S. Army will fund our research. This serum you’re developing is to weaponize the condition.’ Is that even a word Sunil thought. He hated words that ended in ‘ize.’ They never led to anything good: weaponize, Africanize, terrorize. Weapons, all of them.” This is, of course, the same U.S. Army that conducted those nuclear tests in the desert, all the while telling the residents who lived downwind of the blasts that they were in no danger. If they were free from danger, then what constitutes danger and to whom?

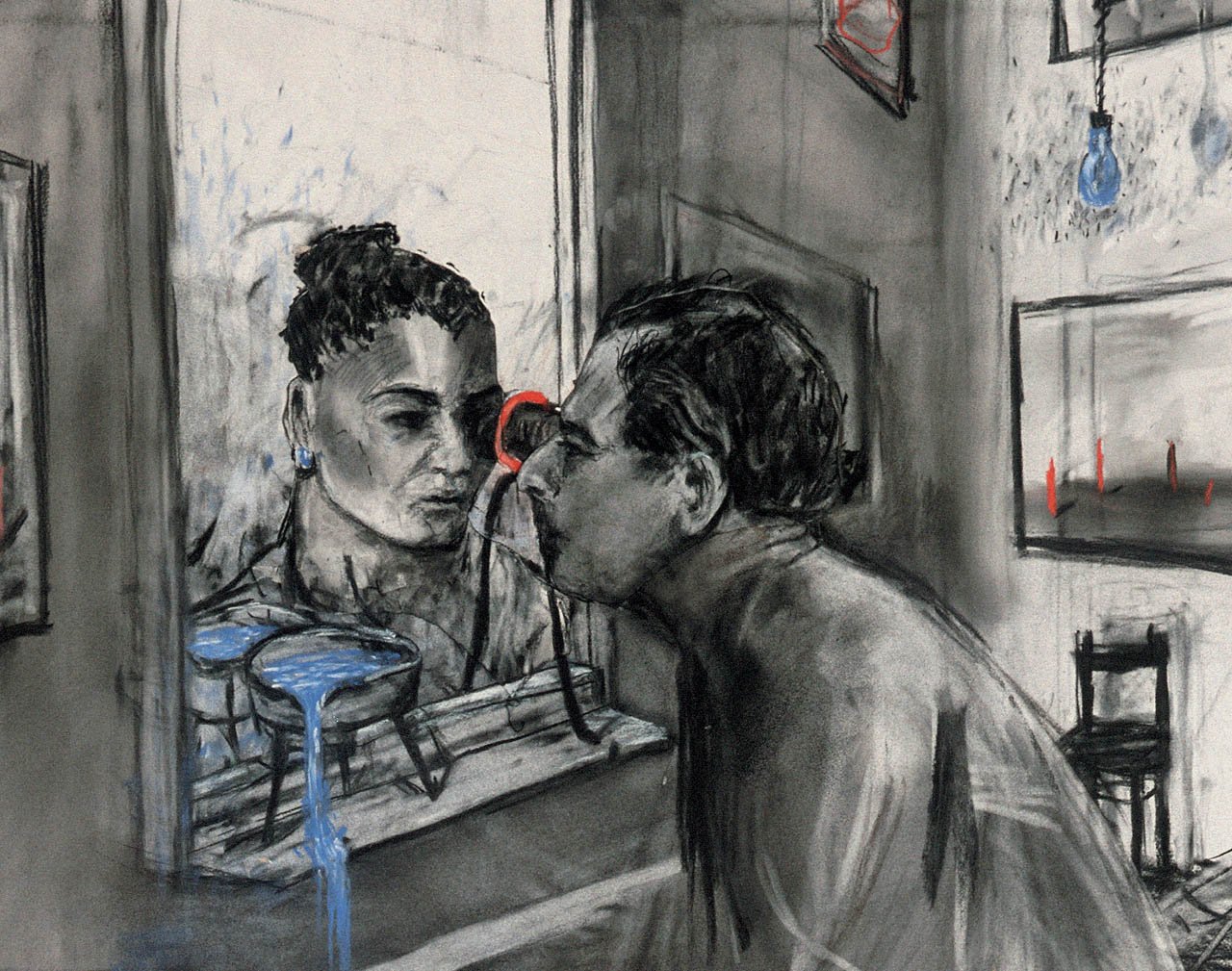

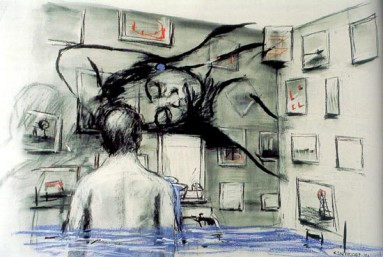

Fire and Water are “nonviable test subjects” and when Brewster bellows at Sunil to get the twins, to “just go get me those monsters,” we are led once more to ask exactly what constitutes viability, not to mention subjectivity, and who and what are the monsters in this novel. Despite Selah’s refusal, it seems that her sons are again to be subjected by those whose subjection formed them. When Sunil returns to his apartment after delivering the twins to the institute he settles in his living room in front of a large print of a William Kentridge painting, Felix in Exile. This is a work that Kentridge, a white South African visual artist, has called a “geography of memory,” a painting that holds the place of a memory of all the atrocities and betrayals that Sunil would rather forget. It’s a painting that speaks to a kind of forensic memory in which Sunil is Felix the witness and also a torturer.

The betrayals add up.

For Sunil, who has selective recollection of his traumatic-too-painful-to-remember past, “everything else was pure scent” which is a play on smell (as the strongest trigger of memory) and also what is absent and present for one with such a “faulty memory.” Faulty memory though is not new and not individual, it is a condition of the times. Likewise, what is seen and felt and heard in this deeply imagined and generous novel says something, to us as readers, about the secret histories of flight and disposability at the heart of our own cities. As James Baldwin wrote, “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction, and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after that innocence is dead turns himself into a monster.” In Abani’s Las Vegas, there is some hope of redemption; lobster claws can offer protection that hands cannot, and freaks and monsters are more than epithets and “medical term[s] for genetic abnormalities,” they are also ethical positions that are occupied and abandoned, made and unmade.