A few months ago, Oscar-winning screenwriter Diablo Cody had a hankering for a good old-fashioned shaming. When she won the Academy Award for Juno, the media latched on to her stripper-turned-writer biography, accentuating her time on the pole and glossing over her skills with the pen. Her memoir Candy Girl, about her dancing days, may have forever pegged her as the stripper who writes rather than the writer who strips. In February, she discussed how difficult it’s been for her to shake that narrative on comedian Marc Maron’s WTF podcast. Maron suggested that women who built their reputation on sex work are “somehow easier to dismiss,” and Cody acknowledged that other women often see writing about sex as an unfair shortcut. Then she brought up yet another sexual paradox to throw on the pile: “Channing Tatum is doing this movie called Magic Mike with Steven Soderbergh about his time as a stripper,” she told Maron. “And I am sitting patiently waiting for people to shame him for this revelation, and it’s not happening. I find it very curious that nobody has anything negative to say.”

And so they don’t. Magic Mike opened last weekend to well-deserved critical accolades and a second-place box office, with little noise from pundits casting aspersions on Tatum’s moral integrity. The movie’s main character, Adam, played by Alex Pettyfer, derives from Tatum’s life experience: After losing a football scholarship, a guileless 19-year-old finds himself sleeping on his sister’s couch in Tampa with swollen biceps and an empty wallet. After answering an ad on Craigslist for a roofing job, Adam runs into magical Mike (Tatum), a self-styled entrepreneur who does construction by day and shaves his legs and lubes his loins after hours, pelvic thrusting onstage to bass-heavy hip-hop at the club Xquisite to the unquenchable desire of co-eds and housewives—apparently, there are no gay men in Tampa.

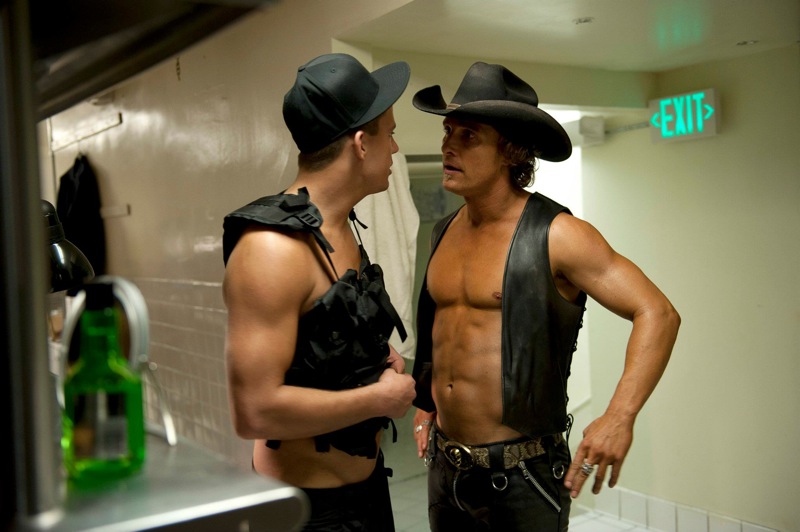

The scene backstage at Xquisite is like a minor-league-baseball locker room: the strippers trade jabs and smack bums — in a heterosexual way, of course. While the dancers themselves are well-developed characters in their off-stage lives, the stripping scenes are not so much sexual as they are comical. The dancers have more campy costume changes than an episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race and are about as erotic as a roller-rink couple’s skate. Ladies in the audience scream for more, but it’s more pink-cheeked embarrassment than hot desire. Despite all the pelvic thrusting, it’s weirdly asexual. Were the men not disrobing, they might as well be party instigators at a bat mitzvah. So, as Cody asked, why is it shameful when a woman takes off her clothes for money and merely funny when men do it?

Were Magic Mike in the hands of a lesser director, the film could have unraveled into a saccharine story of a hooker hunk with a heart of gold, but Soderbergh deploys Mike, Adam, and Dallas, the leader of “the cock kings of Tampa” (played by a delightfully seamy Matthew McConagauhey), to subtly critique capitalism. Filmed in the same bleached palette as Traffic and Out of Sight, Magic Mike depicts characters struggling to square their material and professional desires with the crap economy. Adam gets paid $10 an hour under the table for his construction job because the boss can’t (or won’t) pay union wages. Dallas says if he has kids he won’t send them to school but will instead plonk them in front of Mad Money so they can learn about investing, because what good is education now anyway? Mike feeds his dream of opening a custom-furniture business by hustling construction and auto-detailing gigs as well as stripping. Obsessed with profits and perfection, he doesn’t allow himself to enjoy his tricked-out diesel truck that he ostensibly bought with a stack of crumpled one-dollar bills, leaving the plastic shrink wrap on the interior so he can earn a good trade-in value. Playing the part of the businessman he fancies himself to be, he puts on a suit and glasses to apply for a bank loan but gets turned down because of his “distressed” credit score. “I read the papers,” he sneers to the imperious teller. “The only thing distressed is y’all.” Tellingly, the opening number at Xquisite has the guys donning business suits, playing out the Wall Street power-broker fantasy for women and also for themselves.

Soderbergh uses the guys’ impulse to get naked for money as emblematic of the raw deal all Americans have been handed in the 21st century. But unlike with female strippers, the motivation for these men to shed their G-strings is assumed to be purely financial and not because of some Oedipal issue to replace mommy with a cougar, not because of some bad-boy moral depravity. Their performance actually enhances their masculinity rather than corrupting it, because when they are on stage writhing and strutting, the pressures of making ends meet seem to dissolve, and their chiseled Adonis-like bodies are worshipped like kings.

It’s hard to imagine a young woman’s stripper story serving as an allegory to critique capitalism: woman loses home in foreclosure so now she loses her bra. Imagine if some of Tatum’s recent co-stars were put in the same position, women like Amanda Seyfried, Amanda Bynes, Abbie Cornish -- all of whom, like Tatum, are all Sears-catalog attractive and mid-tier box-office bankable but not exactly know for their acting skills.

Though the same story could be told, it would inevitably veer toward tragedy rather than comedy or, as in the most famous stripper movies, melodrama. Beginning with Gilda, the 1946 cinematic birthplace of the striptease, just removing a single black glove was enough to mark Hayworth’s title character as a harlot. Movies like Striptease and Showgirls reduced Demi Moore and Elizabeth Berkeley to good girls gone bad, making them parables of what danger awaits women in the seedy underbelly of strip clubs. The Wrestler is a notable exception, because Darren Aronofsky and Robert Siegel developed Marisa Tomei’s stripper character with disarming empathy and realism, as she struggles with the ravages of age diminishing her product. But her character doesn’t receive a full arc; she plays foil to Mickey Rourke’s lead. It remains to be seen a film that can develop a female sex worker to be more than the sum of her silicone.

Given the disparity in the portrayals of male and female stripping, it would seem that Tatum’s all-male revue and Tomei’s drug-addled stripper are in two totally different professions. They both take off their clothes, so why are the portrayals so distinct? “Male stripping is just a completely different animal,” says Chloe, a stripper in her early 30s who has worked in high-end clubs in southern California for the past six years and is now entering law school. “It’s just not as sexual. Men who come to the club where I work are, like Chris Rock said, predators on the prairie stalking their prey, and the girls who go in big groups to an all-male revue in Las Vegas are screaming and having fun with their girlfriends. It’s totally different.”

The stripping in Magic Mike is a cross between burlesque and a community theater production of Anything Goes. The women in the audience are gussied up like they are going out to a nightclub, not lurking alone in a dark corner, wearing sweatpants for more sensation during a lap dance, as Cody described the strip club’s male clientele in Candy Girl. The movie sets up elaborate scenarios meant to act out women’s alleged fantasies: a woman is plucked from the crowd to be tied to a tree while Tarzan has his way with her; a life-size Ken doll becomes sentient and walks robotically toward his Barbie; and many, many law enforcement and military uniforms are removed. The women watching jump to their feet and scream. While the dancers onstage animate a fantasy, the female audience members also engage in role playing. As men take on the role of a hunky fire fighter, female audience members take on the role of the objectifier rather than the object. It’s fun, maybe even empowering, to treat a man like a piece of meat—it was, at the very least, deeply satisfying for the audience of straight women and gay men with whom I shared a screening.

Despite their objectification, though, Magic Mike depicts the men as in control at all times. Even when the male dancers are in various states of undress, they are the ones lifting audience members out of their chairs, dry-humping them to the squeals of their girlfriends, and raking manicured digits down rippling six-packs. But according to one former dancer, Magic Mike might not tell the whole story of power dynamics. Travis, a body builder who dabbled in stripping for a while and now works as a bouncer at Chloe’s club, says, “Women are more aggressive than you’d think. You have to submit to a lot of things that happen. Sex was a given.”

Whereas male customers are bound by strip-club decorum -- you don’t touch the dancers; you can request a lap dance but she isn’t required to give you one -- women can get uninhibitedly aggressive. “They want you to take everything off,” Travis says, but this can be a problem for many male dancers, who use rings, pumps, and extensions to keep their penises erect for the duration of the set. Travis mostly performed for bachelorette parties with another guy, dancing for 15 or 20 women at house parties. “When you’re at somebody’s house, there are no rules.” Often, women would want more, and he and his stripper colleagues were expected to have sex with the brides-to-be. “Certain situations, like getting pushed into a room with a chick and being expected to do certain things would make me uncomfortable. But, look, I was a young single guy.” There was never a threat of violence. “Women expected that I’d like being grabbed at automatically because I’m a guy,” Travis remembers, “but you do end up feeling like a piece of meat.” And the more you let the clients grab, the more women would tip. Since the company that contracted Travis took half of the flat rate charged for his services (usually $300) and the other half had to be split with the other dancer, tips made a night worthwhile.

The sex industry might be the only sector in which women outearn men. Travis told me about a 42-year-old dancer at his club who earns an average $1,300 a night. “She works the floor nonstop. She doesn’t sit down and drink with customers. She only dances clean,” meaning that she doesn’t “get on her knees” or “vibrate,” simulating oral sex during a lap dance. Chloe paid off all her student loans and is racking up savings for law school. And even if a woman wants the same kind of independent entrepreneurship Mike craves in his custom furniture business, women still have a harder time leaving when such good money is guaranteed. It’s easier for a man to walk away from stripping and pursue his dreams.

In the film, mesmerizing Mike falls for Adam’s older sister Brooke who is dubious of his tawdry profession. “You’re a 30-year-old bullshit male stripper!” Brooke admonishes him. “I am not my job,” Mike snaps back. In America at the beginning of the 21st century, this sentiment will resonate with many. So many educated people must work jobs that they are overqualified to do, so many must patch together three or four part-time jobs to make a living, so many are stuck working in fields they expected to be retired from years ago. And yet, because we live in a country where work takes up the lion’s share of our lives, we do derive self-worth from our job title, and let others inflate or diminish us accordingly. Our society does in fact define us by our jobs. Throw making money off of sex into that equation, and the stakes are raised.