Dating has left behind the modernist binaries that once defined it. To survey the field we now face, we need a map

A pastiche, with apologies to Rosalind Krauss

i.

Over the past 10 years, rather surprising things have come to be called “dating”: midnight invitations to parties-in-progress, hookups arranged entirely by email, or one-on-one excursions to movies and drinks with a friend with whom one has drunkenly slept. Some long-term partners use “dating” to describe the relationship that each of them has to a third, who supports both as their patron, while others take “dating” to mean lying about in their pajamas and queuing up yet another episode of Breaking Bad.

No category could cover such a motley of activities unless that category had become almost infinitely malleable. And indeed the meaning of the term dating has grown so vague that it obscures the very thing it is supposed to capture. Boomer parents bewail the hookup culture that they say has replaced dating, while their adult children stare into the abyss of Craigslist and wonder whether they even know what dating is. Yet we would submit that we know very well what dating is. And one of the things we know is that it is a historically bounded category, not an eternal one.

Dating, we propose, was courtship in what we might call its high-modernist phase. A classical phase preceded it. And in 2014, long after what many have declared a “death of dating,” we are fully within an era of romantic postmodernism. In each of these periods, courtship obeys a cultural logic that may appear inflexible. But any strict definition of courtship would be misleading. Because, in fact, each of these periods creates a field of possibility that can support a variety of romantic and sexual practices. To survey the field we face at present, we need a map.

ii.

But first, some backstory. For many centuries, the logic of middle-class courtship remained inseparable from the logic of marriage. Before the dawn of dating, the dominant form of such courtship was “calling.” According to custom, young women in the Victorian era extended invitations to suitable young men, asking them to visit their homes at appointed times. Typically, the members of the prospective couple met in her family parlor, supervised by her female relatives.

To the present day reader, this mating dance may resemble nothing so much as a kind of awkward “office hours” of the heart. But in the 19th century, the setting and rituals of calling powerfully symbolized the marriage one hoped to obtain from the process. A man and a woman sat together in a domestic space that the women of her family watched over. If the call went well, more calls followed; eventually, the couple married and began to sit as husband and wife in their own domestic space—which she would happily manage for the rest of her life.

For a century, calling successfully produced enormous numbers of households. But these classical courtship conventions were not immutable. There came a time when their logic began to fail. In the early 20th century, would-be paramours gradually began leaving the parlor. By the 1920s men no longer accepted invitations to call on women—instead, they took them out. This modernist period of courtship introduced the idea of the “date”—in which “the call” lived on only as a marker. I’ll pick you up at seven. The essential homelessness of the date was written into its very structure: It required a departure time.

The modern date was the opposite of the call, the call’s first negation. Instead of a woman inviting a man into her domestic space, a man invited a woman out of her home and into public—where he paid for things and therefore called the shots. Rather than reproducing the domestic life of their parents, dating promised young men and women liberation. It let them loose in a separate world centered on urban sites of spectacle and mass consumption—on movie theaters and dance halls, boardwalks and restaurants. Young daters publicly traded time, company, and money. They soon realized that, even if such novel settings allowed them to ditch their chaperones, dating made its own demands.

Young men and women no longer had to play at housework, but in exchange they took on new forms of labor. They had to select the sorts of fashions, foods, and activities that would make them appear attractive to prospective mates. And, of course, they needed to earn enough money to buy those fashions, food, and tickets. Dating’s “site,” its symbolic content, was not the home but the marketplace. It was training not for marriage, but for productive membership in consumer society. As such, dating became one of our most robust cultural forms. Through it, the field of courtship began to expand.

Over the course of the 20th century, dating loosened and finally unraveled the Victorian sexual mores and gender roles that had guided the 19th century middle class. The culture of calling had treated marriage and celibacy as if they stood in opposition. To be not married was to be celibate, and to be not-celibate was to be married. But as dating became the dominant form of courtship, the relationship between these terms began to shift. Promiscuity ceased to be only a mark of aristocratic privilege or lower-class degeneration. Dating made sleeping around bourgeois—respectable. It thus introduced a third term in the field of oppositions that had long defined Western courtship.

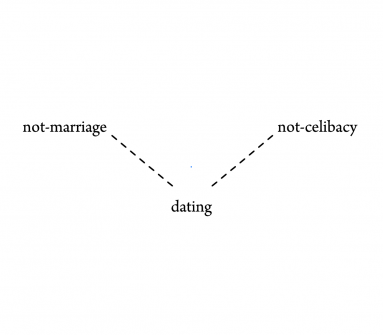

If we may borrow the terms from the original opposition, we might say that dating emerged as an alternative to the old binary of marriage versus celibacy; more specifically, it negated marriage and celibacy. Dating was the sum of not-marriage, and not-celibacy. It was before or proximate to marriage, but not marriage. To date was not to be assured of sex. But to date conventionally was to rule out celibacy, by which we mean the deliberate refusal of sexual romance.

However, as dating developed over the 20th century, it gradually lost the stable repertoire of activities and spaces with which it was first associated. Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, the only thing we can be certain of with respect to dating is that the dater is neither (monogamously) married nor celibate. More and more, “dating” refers simply to a combination of negations. The term has become a catch-all for any romantic activity that is neither marriage nor celibacy. But of course even this broadest definition of dating does not even begin to cover the spectrum of romantic experiences available to us.

iii.

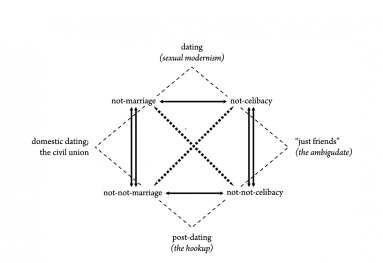

It is crucial, then, that we expand our description of romance to include the whole structural logic of contemporary romance, beyond dating. Using dating as our starting point, we can create a logically expanded map. We will start by illustrating dating’s most basic, minimal definition.

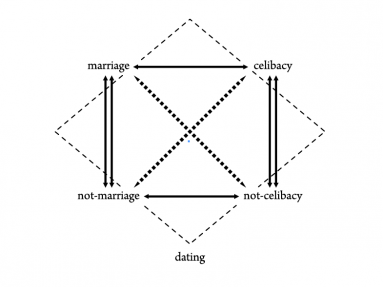

In order to expand the field of dating, we can borrow a tool that French structuralist social scientists called a Klein set or Piaget group. The Klein set uses a series of logical expansions to transform any supposed binary into a quarternary field. That is, it allows us to build upon a familiar opposition by showing that each of its components belongs to another opposition. For instance, the Klein set shows that marriage is not only opposed to celibacy; marriage is also opposed to not-marriage in all its forms. And celibacy is not only the opposite of marriage; there are many varieties of not-celibacy that one might live. The expanded diagram acknowledges that marriage and celibacy—as positive terms—are also ideas that organize much contemporary romantic behavior. But it also allows us to begin sketching in activities and attitudes that the old framework had no means to represent.

If we expand the classical marriage-celibacy opposition, we get a diagram that looks like this:

Here, dating is no longer only the middle term between two things that it is not. Rather, dating becomes one term on the periphery of a field in which there are other possibilities with different structures. The diagram enables us to envision three other categories. Each of them is a condition of the field itself, but none of them assimilable to mere dating. They are:

The possible combination of marriage and not-marriage yields a number of intermediary forms. For example, cohabitation is not necessarily marriage, nor is it not-marriage. One who is, or has, a mistress also sits in this quadrant. The ur-form of marriage plus not-marriage may be the affair: the married person’s passionate commitment to betrayal. This quadrant is particularly French.

The addition of celibacy and not celibacy brings us to a set of social practices that lie between sex and its antithesis. Desire has traditionally been connected to pursuit of contact. But today we have many ways of decoupling the two. Innumerable technologies—online porn, Tinder, Grindr, camgirls, Chatroulette, and Snapchat—allow us to engage in forms of sex that leave the body untouched. The addition of not-celibacy to celibacy allows even the chaste, who don’t get any, to get off.

The marriage-celibacy complex lies at the top of the map; it represents dating’s equal and opposing force. Evidence abounds that our culture considers marriage unsexy by definition. The age of dating has created countless, powerful images of sexless marriage as the extreme to which dating is opposed: the life of minivans wending toward kids’ soccer games, takeout, sweatpants, Netflix binges, and bed-death. Marriage is commitment; dating is freedom: the freedom to leave the domestic sphere, to define one’s self by one’s choices on the sexual market. Yet, for many people, marriage remains dating’s goal. We recoil in horror before an eternity of sexlessness, even as we aspire to it.

iv.

The logic of modernist dating is in crisis. Perhaps this is because, despite conservative efforts to preserve them, marriage and celibacy are no longer strong cultural forms. Or at least they are not as captivating to 21st century audiences as dating. Dating, rather than simply standing for the state of not-marriage, has become a productive cultural trope in its own right.

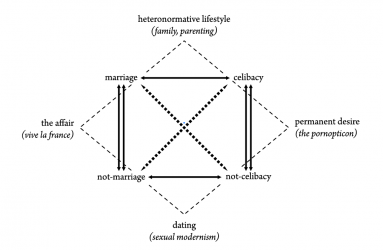

If we accept this fact, we can introduce another set of oppositions into our diagram. That is, we can further expand the field. Marriage and celibacy still fit into this new schema, because ideas about sex and commitment still govern our thinking about romance. But postmodern courtship subjects these terms to a double negation. Imagine, then, that the opposite of not-marriage is not marriage, but, rather, not-not-marriage: the state of not actively avoiding marriage. The opposite of not-celibacy is, similarly, not-not-celibacy: it is not the active pursuit of a sexual interest, but rather an openness to the possibility of sex. These doubly-negative terms can help us more clearly recognize several novel forms of contemporary relationship.

What lies between not-marriage and not-not-marriage? Those who are neither married nor actively avoiding marriage: they are the domestic daters, the cohabitating couple whose members are still trying each other on for size. Their relationship may have the feel of an expediently “shared lease” or of a dress rehearsal for permanent domesticity. Either way, it remains distinct from the French-style affair or ménage, which accepts its place outside the marriage-celibacy complex. Domestic daters live together in conflict. They do not know whether or not their arrangement will lead to marriage. Perhaps one party hopes for marriage while the other is certain it will not happen. More likely, both are ambivalent. Either way, this quadrant is very 20-something.

The union of not-marriage and not-not-marriage also yields a newly-emergent legal category: the civil union. Many couples obtain a civil union because they would like to marry, but the state will not let them. Crucially they are not-married: they do not have the rights and privileges of marriage. Yet they are not-not-married, because they live and feel married in almost every other sense.

On the other side of the graph, there is the addition of not-celibate, and not-not-celibate. This terminology is vexing, yet the situation it describes is all too familiar. We associate with many people to whom we are attracted, or to whom we could become attracted, but with whom we have decided to remain “just friends.” At least for the time being. Ambigudates do not promise sex, but they don’t not, either. Some just-friends, after trying and failing to turn ambiguous relationships into the sexual relationships they desire, begin to resent this quadrant. On innumerable Reddit threads and “Men’s Rights” message boards, angry men rail against their exile to what they have dubbed “the friend zone.” But such complaints—that one has been unilaterally banished to friendship—misunderstand the zone of “just friends.” It takes two to ambigudate. And two—or more!—can go on happily ambigudating for years.

At the bottom of this newly-expanded field of dating sit several of our most beguiling cultural forms: the fuck buddy, friend with benefits, erotic friendship. These forms of relationship forgo marriage’s contractual stability, and its guarantee of sexual access. This entire quadrant may fall under the category of “postdating.” Its possibilities range from the destructive and exploitative to the passionately new. Rather than assimilate these relationships to the rules of dating, we would do well to investigate this field more rigorously, on its own terms. It deserves its own radically expanded map.

These transformations don’t necessarily represent progress toward ever better, freer modes of being. They represent changes in the structural possibilities that govern sex, pleasure, and reproduction at any given moment in time. Transformations in the field of courtship are historical events. A structural analysis, therefore, is not enough. A complete map still leaves us with the task of explanation. How do institutions uphold these structures, and what factors have allowed them to change at specific moments? To really understand where we are now, and where we might go from here, we don’t just need a bigger diagram. We need a history of dating.