There’s a reason Rachel Kushner's novel of revolution is narrated by a naïve young girl.

Reviews of Rachel Kushner’s new novel, The Flamethrowers, have tended to pay most attention to the book’s historical setting. The year is 1976, New York’s Lower East Side is in a state of permanent vacation and temporary neglect, and Italy is in the throes of possible revolution, a period known as the Years of Lead. Reviewers of Kushner’s 2008 debut, Telex From Cuba, a roundabout look at the American families working for the United Fruit company in Cuba during the 1958 revolution, were similarly attentive to that book’s backdrop and politics. Praised for bringing “Cuban-American history to life,” Telex seemed to do little more than that; the characters were unmemorable, while the setting and the stylistic approach, with its slippery perspectives, overabundance of digressions, and tonal ambivalence, took center stage. In The Flamethrowers, on the other hand, the narrative derives more than a passing relevance from the times and places in which it is rooted, as it follows the main character, a girl referred to only as Reno — in reference to her hometown — as she moves from the salt flats of Nevada to Manhattan and finally, after meeting the son of an Italian motorcycle manufacturer, to Italy. There’s a reason this point in history is narrated by a naïve young girl: Revolutions are the confused youth of history, paralyzed by possibility even as they’re enthralled by it. And given the flashiness of the subject matter — motorcycles, sex, rebellion — it’s to Kushner’s credit that this time around the setting doesn’t distract from the story. Reno’s trials aren’t simply laid over the real material of history, nor are they merely a way to get from A to B. The Flamethrowers is as much about this young woman’s experience of young womanhood as it is about anything else.

The novel’s two major themes — revolution and violence on the one hand and femininity and youth on the other — are intimately connected. As a child, Reno’s lover Sandro’s favorite characters in his paper doll army are the flamethrowers, though he’s warned that “they were obvious and slow-moving targets” that were “shown no mercy” if caught. Yet Sandro can’t help but love them best, “though he didn’t know if his interest was a reverence or a kind of pity.” He feels something similar, later in life, about the girls he gets involved with. Sandro’s father’s obsession with machines, specifically with racing motorcycles, likewise overlaps with his obsession with young women. The novel’s epigraph, FAC UT ARDEAT, or “made to burn,” comes from an engraving on the father’s fireplace at his country house in Bellagio. The phrase, etched into the minds and materials of T.P. Valera and his son, is one they want to impress onto the women they encounter too. As Reno observes at one point: “A funny thing about women and machines: the combination made men curious. They seemed to think it had something to do with them.”

Reno, like other women her age, is expected to shine bright and hot before smoldering out. Her presence is desired for the momentary fascination it provides; she can easily be dismissed and replaced. And just as she is treated as expendable, so does Reno treat her time and experiences. Joan Didion, writing of her experience living in New York as a twenty-something, describes a similar naiveté: “I still believed in possibilities then, still had the sense . . . that something extraordinary would happen any minute, any day, any month.” Finally she realizes that in fact she is already living, “that some things are in fact irrevocable and that it had counted after all, every evasion and every procrastination, every mistake, every word, all of it.” For both Didion and Reno, to leave things up to chance is to accept a kind of personal disposability.

Reno acknowledges that, by contrast, both Sandro and his friend Ronnie “had a palpable sense of their own future,” though she isn’t disturbed by being different from them:

I was not like either Sandro or Ronnie. Chance, to me, had a kind of absolute logic to it. I revered it more than I did actual logic, the kind that was built from solid materials, from reason and from fact. Anything could be reasoned into being, or reasoned away, with words, desires, rationales.

Tellingly, perhaps, Reno is used and discarded by those who act as if they have free will, places to go, things to accomplish, while she — proudly, innocently — treats the future as something that she can’t quite be bothered with. When Sandro tells her that she doesn’t have to do anything, that her experience is enough because “a young woman is a conduit,” she believes him. “Some people might consider that passivity but I did not,” she tells us. “I considered it living.”

As Sandro puts it, a young woman doesn’t have to do anything to get something to happen. She can simply be, wearing herself as art, performing her sexuality and youth. She need put forward no action in exchange for experience, only a willingness to be acted upon. It’s this malleability, among other things, that make her so desirable to Sandro and to the culture at large.

Yet as much as she claims to value chance, her desires seem to cloud its utility. Ronnie, during a single night with Reno before she meets Sandro, takes a Borsalino fedora from her apartment, one that will reappear later in the narrative to devastating effect. “I had said something embarrassing about the Borsalino being already his, that it had been waiting for him in my apartment,” Reno tells us. “I was doing that thing the infatuated do, stitching destiny onto the person we want stitched to us.” As much as she despises a maudlin sense of fate, she’s still hurt when she wakes up to find Ronnie gone, having imagined this night to be the first of many.

And as ambivalent as she is about destiny in matters of love, she distrusts free will even more. Sandro, she tells us, “had a way of talking about our courtship that presumed there was choice to it. Perhaps this was simply a difference between us. I did not experience love as a choice, ‘I think I will love this or that person.’ If there was no imperative, it was not love. But Sandro spoke as if he’d seen me on the street and simply made his selection.” Reno’s real philosophy, then, is not really one of chance over fate but of passivity over action.

Reno tries to resist the dominance of the two future-obsessed men in her life, Sandro and Ronnie, by paying attention to the present. When the pair take her to see the sculpture of a slave girl at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, her companions insist on the sculpture’s beauty, while Reno can’t see past her humanity. All she can think, looking at the marble, is “This is a young slave.” Her thoughts are similarly captured by the suffering of one of Ronnie’s love interests, a girl on his “layaway plan.” In the scene, the group is still out at a bar, though Ronnie was supposed to have met her hours ago. “Had she taken a bath and given up, gone to sleep?” Reno wonders. “Or put on more lipstick, gone out looking for Ronnie, but to the wrong place?” For all the things she doesn’t do, all the actions she doesn’t take, Reno is intensely aware and critical, something Sandro and Ronnie are not.

In this way, Reno isn’t totally taken in by her companions. Where Sandro sees a film about life as an industrial worker, Reno sees a film about “being a woman, about caring and not caring what happens to you.” She questions the asinine displays of masculinity she witnesses, wondering where “the impulse to shoot someone in the hand” or “to hide a gun in your boot” come from. If Reno is passive, her passivity is a way of differentiating herself from the men in her life, a way of escaping the dominance of their concerns and their ways. In place of the obnoxious comments she doesn’t make, the expertise she doesn’t claim to have, she is constantly observing and inquiring, if not out loud to others, then to herself.

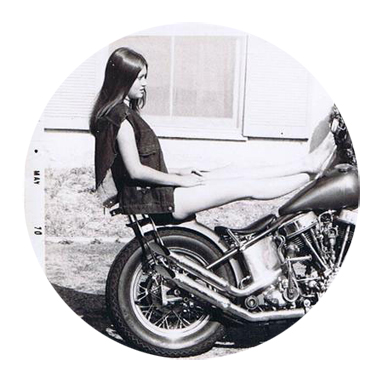

And just as she evades total subordinance, Reno also avoids victimhood. Reno does not die, she does not despair, and she doesn’t break down. The difference has something to do with her connection to a machine: “It was only a motorcycle but it felt like a mode of being.” When a man on the street watches her ride by and gives her a thumbs-up, she explains, “He wasn’t coming on to me. He was envious. He wanted what I had like a man might want something another man has.” The move may seem too obvious on Kushner’s part, the motorcycle a stock way to toughen up a routine heroine, but it works because the toughness isn’t complete. Reno isn’t saved by being a hot, gap-toothed blonde on a motorcycle, that metonym for danger; instead she is complicated by it. We understand that Reno is neither as aggressive as the motorcycle signals she might be nor as passive as a contrast might suggest. And the motorcycle, in the hands of this more or less tractable, acquiescent girl, yields an irony, for the machine that led her to a supporting role in a man’s life and a revolution is also the thing that might enable a new life and way of being, one that doesn’t depend on men or sex.

At novel’s end, Reno seems to be confronting her former complaisance. As it promised, her experience in Italy has rendered some sort of transformation: “When you’re young, being with someone else can almost seem like an event. It is an event when you’re young,” she tells us. “But it isn’t enough.” The reader can’t help but wonder if it’s enough, upon emerging from a tumultuous Roman revolution, to realize, as Reno does, that you don’t want to date, you want to make art. But perhaps it’s only the first step toward the next part of her life, the beginning of watching the fire die. She is, after all, “still young.” Reno’s last utterance, not at the end of the story, but at the end of the novel, casts her life in something resembling realistic failure: “Leave, with no answer. Move on to the next question.” And so history and Reno’s life cycle back on themselves. Like Italy, wavering on the edge of revolution in the Years of Lead, Reno looks over the edge, around herself, and then gets tired of waiting.

Reno is a quiet and ambivalent observer, pronouncing on events without acting on them, criticizing without proposing alternatives. The novel itself, observing Reno, takes a similarly ambiguous attitude. In Manhattan Reno attends dinner parties for elite New York artists, ridiculous displays of ego and self-involvement; in Italy, she witnesses the failures of revolutionary action in Rome’s lower class. Is Reno’s relative disengagement from each sphere her failing or that of these two very different worlds? For all the noise they make, neither offers much in the way of change, and little incentive to participate. After all, if “action” is whatever Sandro and his friends are up to, why not reject it? And if Reno’s motorcycle breeds a quiet irony, so does the fact that this novel about art and revolution is narrated by a directionless young girl. What conclusions does Kushner want us to draw? Perhaps only that, as in matters of violence, war, and struggle, action and passivity in a girl’s life are not bound to their moral associations. Action is not necessarily good and passivity is not necessarily bad. There’s no room for Reno in a universe in which active women are considered strong and passive women are not. At the same time, Reno reminds us, passivity isn’t always the opposite of action, but rather its lining. Some actions do nothing; some inaction can do a great deal. And sometimes being passive in the face of unbridled freedom is the most revolutionary thing in the world.