Rage is the disavowed truth of what resistance tends toward.

“Don’t expect to see any explosion today. It’s too early...or too late.” - Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks

Fire is raging across Turtle Island. Fire over Ferguson. Fire in the streets. Fires of protection in defense of Indigenous territories. Burning police cars: a hallmark of indignation, sedition or infiltration, provocateur-led sabotage. Cars aflame in Ferguson and Crown Heights, RCMP vehicles and tires ablaze in Elsipogtog. Fires that clear, nurture, destroy.

It’s too early or too late. The latest instantiation of respectability politics is performed as acquiescence to a status quo that cannot hold. It is a grim acceptance of governance ruled by rights and recognition, sunk under the state’s delineation of what matters, what is counted as “morally legitimate” politics, authentic protest, acceptable forms of resistance.

But resistance contests these limits of respectability. In a war of defiance, resistance marks a union of forces that seeks to out-maneuver the policing of its legitimate parameters, that moves to negate its suppression. Anger forces itself to the surface. Will this rage be negated? Anishinaabe writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson states:

I am repeatedly told that I cannot be angry if I want transformative change—that the expression of anger and rage as emotions are wrong, misguided, and counter-productive to the movement. The underlying message in such statements is that we, as Indigenous and Black peoples, are not allowed to express a full range of human emotions. We are encouraged to suppress responses that are not deemed palatable or respectable to settler society.

But the correct emotional response to violence targeting our families is rage.

The temporality of resistance is the present. To resist is to affirm presence. Rage is the disavowed truth of what resistance tends toward: Outrage aimed at freedom, collective action rooted in love, the active defiance of injustice. Until we’re all free: A refrain turned echo. A call to commune with other collectivities in struggle. Until we’re all free. That this refrain should find resonance in our present affirms both the failings of the settler colonial system to realize any dreams of freedom and the people’s continued will to resist. To recognize the necessity of such co-resistance against erasure and death is to support each other in giving voice to collective outrage. Protest becomes the creative affirmation of the world to be realized here. Now. We already know whose lives matter and whose must be sacrificed at the altar of democracy.

Our flight from the future is a fight for the present.

From Fanon to Ferguson to the Unist’ot’en, Black and Indigenous struggles for freedom across the colonized lands of Turtle Island will be won in combat against the spectacle of a society losing control of its contradictions.

* * *

Into this present crisis steps Yellowknives Dene scholar Glen Sean Coulthard, trailing dog-eared copies of Fanon, Marx, Hegel and Nietzsche, but keeping his eye on a decolonial horizon forged by an Indigenous resurgence movement that seeks “to radically transform the colonial power relations that have come to dominate our present.”

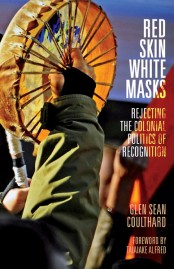

Red Skin, White Masks

Red Skin, White MasksRejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition

Glen Sean Coulthard

University of Minnesota Press

2014

The strength of Coulthard’s intervention derives its potency not only from the precision of its analytic critique of how liberal politics works to defuse resistance against settler colonialism, but also from its unapologetic advocacy for anticolonial outrage. Defying the vast majority of Indigenous scholarship and “Aboriginal” public discourse that dutifully reinforces colonial tropes of victimization, pathologized suffering, historical wounds, and colonial “legacies,” coupled with future-oriented settler narratives of “healing” and “reconciliation,” Red Skin White Masks makes space for rage. By arguing for both its necessity and its expression to be realized in Indigenous struggles for freedom, Coulthard emboldens his claim that the liberatory power of resistance is co-determined by the force of collective outrage, when channeled against structural and psycho-affective forms of colonial subjugation. Rage, so directed, becomes an affirmation of critical consciousness and a means of transforming colonized subjectivity into empowering and disalienating collective action to #IndictTheSystem and #ShutItDown.

Red Skin White Masks is haunted everywhere by the ghost of Fanon, from its titular nod to Black Skin, White Masks to its foreword written by Kanien'kehá:ka scholar Taiaiake Alfred, which offers a wry remix of Sartre’s infamous introduction to Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, Fanon’s imprint is evident at multiple aesthetic and political levels throughout the text. Coulthard finds his most ardent form of intellectual kinship with Fanon’s unmatched diagnosis of colonial (modalities of) subjectivization, or how colonizers work to produce their subjects’ psychological states. In colonial subjectivization, governance is stolen from collective articulations of Indigenous ontologies and polities and turned into subsumptive forms of neoliberal individualism. Colonialism’s desired future is the transformation of Indigenous anticolonial resistance into the colonial subject’s resistance of the self. This restrictive form of subjection or self-rule is effective precisely because of its capacity to “manage” Indigenous resistance and sublimate rage:

settler-colonial rule is a form of governmentality: a relatively diffuse set of governing relations that operate through a circumscribed mode of recognition that structurally ensures continued access to Indigenous peoples’ land and resources by producing neocolonial subjectivities that coopt Indigenous people into becoming instruments of their own dispossession.

Colonialism sublimates rage by suppressing what Nietzsche would call ressentiment against the theft of Indigenous land and resources and the psychic subjection of Indigenous consciousness, by making them unpalatable to both colonizer and colonized. Resistant rage is thus made “distasteful” even to the colonized subject, for whom respectability and acceptance by settler society come to matter most. Indigenous people become complicit instruments not only in “their own dispossession,” but in their subjection as such.

Against this logic, Coulthard contends that Indigenous people cannot afford to disallow and disavow rage. “[C]ollective expressions of anger and resentment,” he states, “can help prompt the very forms of self-affirmative praxis that generate rehabilitated Indigenous subjectivities and decolonized forms of life.” Anger and resentment can be generative acts of resistance. Rage is not simply necessary: It can become righteous revenge. Although Coulthard stops short of advocating for violence or outright vengeance against settlers, he acknowledges that the swift current of resentment is a critical live wire in the storm of rhetoric and land-based contention that comprises Indigenous resistance to colonial rule.

If the future is founded in a fight for the present, the current terrain of anticolonial struggle on Turtle Island is mapped by Indigenous ontological understandings of land and landscape. Indigenous peoples do not see the land as the settler does. Indigenous understandings of place do not rest on romantic memories of pre-contact freedom; they are not simply cartographic, settler portraits of a territory that has been redrawn according to Indigenous coordinates. Rather, anticolonial struggle is founded within a field of relations born of the land. Coulthard calls this “grounded normativity”—“the modalities of Indigenous land-connected practices and longstanding experiential knowledge that inform and structure our ethical engagements with the world and our relationships with human and nonhuman others over time.” Grounded normativity is the rooted, interconnected means by which Indigenous struggles are both waged and expressed, through individual and collective actions against empire. Indigenous rage then is, quite literally, grounded in the resurgence of Indigenous life and derived from a shared love of place, land, culture, and nation. “Place”, Coulthard has written, “is a way of knowing, experiencing, and relating with the world, and [Indigenous] ways of knowing often guide forms of resistance to power relations that threaten to erase or destroy our senses of place.” This praxis of being-in-place is necessarily lived in resistance to the colonial disruption of Indigenous relational existence and ethical continuance.

To reject the politics of recognition, for Coulthard, demands that Indigenous people refuse the very terms by which their existence is constrained and restricted in advance by colonial codifications of legitimacy and authority. This constraint is evident both at the level of systems of settler colonial governance and at the level of the individuated self. To throw off colonized subjectivity in favour of an authentic way of resisting that recuperates the power of Indigenous knowledge and being in place, we must negate these systems, Coulthard argues, in order to affirm ourselves. This is a radical claim only to the extent that we have in literal terms been physically and psychically removed from our roots, reduced to navigating colonial paths paved over the broken ground of Indigenous homelands.

The settler colonialism practiced by capitalism induces a particular form of enslavement to machine-like systems within which resistance is confined to a narrow paradigm of liberal individual subjectivization. But Red Skin White Masks demands more from us. Coulthard compels us to act in service to liberation forged on our own terms through an “ethics of desubjectification...directed away from the assimilative lure of statist politics of recognition, and instead...fashioned toward our own on-the-ground struggles of freedom.” Against enticements toward ‘better inclusion’ within a failed system, Coulthard calls for Indigenous people to turn away from a freedom defined and determined by the state. Despite the deep asymmetries of power, structural antagonisms, and systemic inequities produced by settler colonial rule, Red Skin White Masks is able to recenter the flames of anticolonial resistance at our feet, on the ground where we stand, in the land and the relationships from which we derive our continued existence.

Red Skin White Masks is a rhetorical act of protection that defends Indigenous existence against erasure by calling Indigenous people back to the fires we have been designated to protect, while cautioning us against accepting the perilous trap of colonial mis/recognition as the basis from which to imagine (false) forms of freedom. There is no freedom to be found in a settler state, either one that would seek to give it or take it away.

Those looking for a placid overview of contemporary Indigenous politics in Canada or for a conciliatory narrative of against-all-odds Aboriginal “comeback” will find no safe haven here. Red Skin White Masks has no time for false optimism. Coulthard offers an urgent and much-needed call to resistant arms at a time when myriad forms of systemic, material and symbolic violence continue to be enacted against Indigenous people and their lands. As the Idle No More movement solicits poetic tributes to commemorate its Indigenous rights-based mobilization from two winters ago, yet another grand jury “declines to indict” a white police officer in the unrepentant killing of an innocent Black person. As more names are added to the already intolerable total of more than 1,200 Indigenous women and girls that have been murdered or disappeared in Canada in the past three decades, we are urged, simply, to make peace with the present, to “keep calm and #IdleNoMore on.”

This, while the fires in our communities continue to spread.

Coulthard argues against the lull of the settler’s desire for calm, with its acerbic pleas to return things to the way they have always been. “Settler-colonialism,” he claims, “should not be seen as deriving its reproductive force solely from its strictly repressive and violent features, but rather from its ability to produce forms of life that make settler-colonialism’s constitutive hierarchies seem natural.” Settler-colonialism naturalizes oppression and acculturates us to violence. Once inured to injustice, we learn to tolerate a system that reproduces itself in and through necropolitical crises of violence, those that have taken the lives of Eric Garner, Mike Brown, Indigenous women and girls, and countless others from our communities. The hegemony of recognition allows dissent and protest to be accommodated within the colonial system, as long as the colonial state remains capable of “calling forth modes of life that mimic its constitutive power features.” By redoubling the logic of opposition to its rule, colonial power reinforces an internal relation of dominance that safeguards its calm colonial exterior while its subjugated citizens burn effigies of empire in the streets.

But Indigenous resistance contends with the false consciousness imposed by colonial logic, countering it through acts of affirmative negation, embodying enactments of Indigenous laws and ontologies and upholding what Coulthard calls other modalities of being, different ways of relating to the world. In these spaces of concerted action and refusal, protest pursues new forms of life against continual crises of state violence. In the streets where Brown and Black bodies die-in. In the lands Indigenous bodies disappear from. Resistance dispels disappearance, impeding the flow of capital and naturalized colonial conduct. Cops hugging protesters. Royal Canadian Mounted Police carrying firewood and tending sacred fires. Resistance disrupts the system’s recursive attempts to police its own image, to appear benign as it chokes out dark voices.

Set against a rising tide of Indigenous mobilization, Red Skin White Masks concludes with a provisional set of theses on resurgence that calls Indigenous communities to break from the silence of colonial domination by building an interconnected movement for decolonization. Although Coulthard avoids prescribing a specific course of collective action, he remains committed to a vision of Indigenous resurgence as a prefigurative politics in which “the methods of decolonization prefigure its aims.” Coulthard’s five theses are attenuated to the need for a resurgent Indigenous politics “that seeks to practice decolonial, gender-emancipatory, and economically non-exploitive alternative structures of [Indigenous] law and sovereign authority” in the midst of an increasingly hostile colonial world. Indigenous and Black communities must affirm what Fanon calls the “alterity of rupture, of struggle and combat.” Critically, Coulthard argues that this must re-center Indigenous feminism at the core of the resurgence. In his words, “‘decolonization' without gender justice is a man-made colonial sham.” Red Skin White Masks admits that by any means remains, as it always has, the means to survive, reclaim power, fight back.

For Fanon, “the real leap consists of introducing invention into life.” Outrage reaches the streets by leaping beyond the borders of acceptability, disrupting the status quo, and intervening into Indigenous and Black lives that are being actively suffocated and systematically disregarded. Invention is a creative act of defiance. It affirms life by refusing to keep calm, to remain docile. Invention demands “endlessly creating” oneself and the world anew. As both invocation and action, invention makes space for fire to breathe, for the full range of emotions called forth by continued injustice to be expressed. Rage is a fire of resistant necessity; it is resonant, righteous, real and alive. Coulthard offers what Aimé Césaire would call “discursive ammunition” for our current struggles, words to feed the fire. With an eye to life beyond colonial-capitalist enclosures and relations, Red Skin White Masks unmasks the present, in the name of freedom still to be won.