Stardew Valley provides the missing piece in a linear account of human history that traces our decline from pastoral paradise to the sterile postcapitalist desert

FROM The Walking Dead to Fallout, the gaming industry is currently obsessed with apocalypse. Long a staple of TV and cinema screens, the zombie has become even more prominent on PlayStations and computers. Added to zombie games are reams of other dystopias, from indie games like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture and the already-cult classic Soma to big-budget productions like the BioShock series. As critics like Frederic Jameson, Slavoj Žižek, and Mark Fisher have all variously pointed out, such images of dystopian futures promote the dangerous idea that only capitalism separates us from a barren wasteland.

But these aren’t quite the only gaming options available to us. Visit the game-downloading site Steam today and among the top sellers you’ll find a game that bucks the trend. Rather than future dystopia, it offers the opposite: a return to the pastoral past. Stardew Valley, an indie-produced farming simulator, or “country-life simulator” as it’s even been called, has racked up a half million sales since February and has overtaken high-profile titles such as Grand Theft Auto 5 and Counter Strike. It might be easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, but easier still, it seems, is imagining the resumption of pastoral serenity.

At first glance, one might see Stardew Valley as a reincarnation of Zynga's FarmVille, the Facebook sensation of 2010 that has now, thankfully, largely left our screens. That game offered the chance to nostalgically harvest crops from our computers, but as with other games made by Zynga, such as Words With Friends and Mafia Wars, the real product being harvested is our Facebook friends, whom we put to use to increase our in-game scores (and then to seek approval for those scores). These so-called social games show us a pretty dystopian present in which (as Heidegger suggested) people themselves are as much our raw materials as crops are.

But Stardew Valley is quite different and has much more in common with Harvest Moon, first released on Super Nintendo in 1996. Like its forerunner this game is individual, practically impossible to share or even discuss with friends, and has no multiplayer feature. Far from connecting us to social and technological media, it's an offer to escape from the modern computer society — one we can indulge in from in front of our computer screen.

So how has Stardew Valley, ostensibly the opposite of current trends, achieved its rise to the top? Though it seems to have little in common with gaming’s apocalyptic portraits of the future, it and other bucolic farming simulators actually provide a necessary counterpart. The gameplay in farming simulators involves organizing people, animals, and the natural environment, planting crops in systematic patterns and experiencing a routine life while playing a key role in a small community. Their picture of a lost era of tightly knit villages where humans lived in organic harmony with nature complements prophesies of a dystopic future in which humans are regimented components of a remorseless capitalistic machine. Farming simulators placate a need for a collective and organized past as an alternative to contemporary chaos.

This may make Stardew Valley seem like a criticism of modern capitalism, but in fact it does little to critique the supposed inevitability of capitalism. Instead it provides the missing piece in a linear account of human history that traces our decline from pastoral paradise to the sterile postcapitalist desert. The best we can do is take comfort in memories and in the fact that we are not further along the inescapable path of destruction.

Stardew Valley offers only the consolations of nostalgia, described by Svetlana Boym in The Future of Nostalgia as “the search for collective memory, a longing for continuity in a fragmented world.” In the past of Stardew Valley we can escape to a world where we are once again “free” to be “human.”

The game’s 16-bit pixilation doubles up this nostalgia, evoking a lost age from the more recent past as well, when video games themselves weren’t as complicit and prefigurative of our coming doom — at least in people’s memory of them. It incorporates elements of Zelda, Pokémon, and other '90s games that are evocative of a gentler past when games, we imagine, were more "pure," "organic," and uncorrupted. It was a time when games really were seen as an escape from the political and social world — an argument that seems defunct today, when games seem to more overtly reflect or distill sociopolitical conflicts.

This ambiance of escape sets Stardew Valley’s in contrast with FarmVille. Whereas FarmVille was fully symbiotic with Facebook, seizing on Facebook’s technological affordances to propagate itself even as it seemed to soften the social network’s neoliberal edges, Stardew Valley is more ambivalent about its medium. Its opening scene, a 16-bit reworking of the opening of Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936), presents a bird’s-eye view of a regimented contemporary office space, a cubicle farm in which workers are conjoined to computers that are presumably in the process of supplanting them.

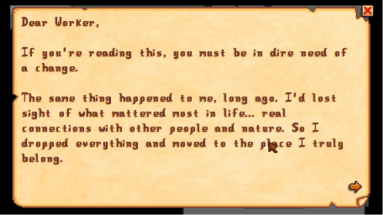

Trapped in gray walls beneath remorseless fluorescent lighting, these workers are cut off from nature and “real” life, but the game offers us a way out via a faux old-timey letter (obviously not an email) inviting us to return to more authentic work tilling the soil.

Of course, this pastoral escape itself demands immersion in a computer simulation.

Stardew Valley addresses this apparent conundrum differently than FarmVille. While FarmVille is nothing more than a masked version of social-capital building, Stardew Valley seems to want to ironize and distance itself from its simulator nature, using retroness as an alibi to make it seem something other than another contemporary extension of computerization deeper into our lives. In presenting itself as a kind of meta-game, Stardew Valley confronts players with the bizarre paradox that a return to the past is at once imaginable and impossible. Ultimately, the game's demonstrative awareness of its paradoxical position instantiates Octave Mannoni’s idea of Freudian fetishist disavowal: "I know very well, but even so…" Stardew Valley knows very well that it is impossible, but let’s dream of pastoral serenity anyway.

***

While Mark Fisher might be right when he recently pointed out that dismissing things as "nostalgic" can be a pretty useless gesture, what we need is further analysis of the peculiar kinds of nostalgia specific to our particular moment. In the case of Stardew Valley, its romanticization of the past serves only to solidify our fear of the future. It teaches us to deal with contemporary alienation through wistful backward glances at an irretrievable past. Though it seems innocuous enough, it resonates with Donald Trump’s calls to “make America great again,” as well as with various European dreams of exiting the E.U. to return to some prelapsarian national serenity in isolation.

As the game’s Joja Corporation — a blend of Wal-mart, Coca-Cola, and Google — starts its inevitable takeover of your peaceful village economy, Stardew Valley's nationalistic indictment of internationalism becomes unmistakable. This is no left critique of corporate globalization but a call for isolationist retreat. Stardew Valley’s image of small-scale self-sufficiency draws from the same impulse to erect walls at borders and seek local salvation through exporting immiseration. Tellingly, the village in Stardew Valley has a bus stop but the bus has broken down, severing the connection between it and the rest of the world.

Stardew Valley’s popularity reflects the difficult political position of the left today. The fact that internationalism is understood as synonymous with the iniquitous capitalist disaster of globalization is preventing the development of solutions on a broad enough scale to address global crises. The task for future games is to posit genuine alternatives and succeed at doing what conservative artifacts like Stardew Valley fail to do. In the new Existential Gamer magazine, a publication that asks gamers to "review themselves" in order to explore the connection between gaming and subjectivity, I argued that Supergiant’s latest game Transistor might offer something like a tech-positive way to revolt, inviting us to embrace ourselves as technological beings.

Such ideas may be comparable with ideas of those such as Erik Olin Wright, whose Envisioning Real Utopias pointed out that it was not so long ago that both the left and the right could easily imagine alternatives to capitalism. Like Varoufakis and Sre?ko Horvat, whose new project DiEM25 is at least a concrete example of internationalist alternative organization, video games could do something other than dream of national serenity through isolation.

But the problem is not that we have only dystopia and no utopian alternatives. Rather Stardew Valley’s popularity suggests that both dystopia and utopia have been appropriated by the right to make capitalism appear the only alternative. We can dream only of tempering its destructiveness. We are still waiting for the video game that offers real hope rather than a nostalgic return to the past.