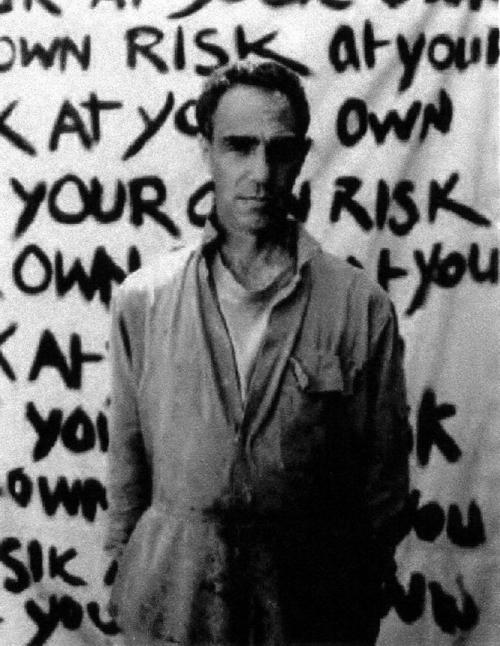

A review of Derek Jarman’s At Your Own Risk

Under the sign of marriage, gay politics seems poised on the brink of completion. Only a few more legislative coups, only a few more senators to lobby, and gays and lesbians will attain the full status of citizens in liberal democracy. The groom and the soldier, prototypically patriarchal fetishes, are the mark of a new sober, mature gay politics. But the facile narrative whereby gays come out of the closet only to prepare for their wedding day with the State abandons the memory of the thousands who died along with the gay world of the liberationist era. It was only paradoxically through the crucible of mass death that a healthy, respectable gay figure could be advanced to petition for inclusion. Now the mainstream gay rights movement thinks of its past as juvenile indulgence at best and suicidal nihilism at worst. That is, if it thinks back at all.

Poised to formally join the straight world, it seems as if all the reactionary moralizing from the Larry Kramers and Andrew Sullivans of the gay community has been successful. They profit from having denigrated the massively innovative public sex culture, which was the social basis of gay politics, as unthinking promiscuity whose risks brought the judgment of AIDS upon us. But far from causing HIV/AIDS, promiscuity was the only way gay men could have invented and adopted safe sex practices faster than the spread of the disease. Well before any vaccines or antiretrovirals, the bonds and relationships of a shared sexual culture erected care networks for the sick and a chthonic politics to counter a renewed onslaught by the State. Yet all that work, pain, and love goes forgotten as the prudish historians posthumously enlist fallen comrades to endorse this sterile vision. As Benjamin said, “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious.”

Against this necromanticism, the reissue of filmmaker Derek Jarman’s more reluctant gospel At Your Own Risk: A Saint’s Testament has the merit of rebuking the melancholic view of the past by recounting Jarman’s unique experience with it, mapping the transit of the (mostly British) gay world from a censured impulse in dormitories and shrubbery to its bright flourishing in London and its defeat at the hands of the pincer attack of disease and Thatcher’s class war. Jarman salvages the image of the life-worlds and social relations gay men invented and insists both on their revolutionary and disruptive character and on the centrality of sex for the love engendered thereby – or rather, on sex as the expression of the fraternal, stranger-oriented love that was the real content of the gay life-world. It was the revelation of this love that was so powerful, as it showed that, in the midst of bourgeois social relations – which Jarman dubs “Heterosoc,” figured as “marriage, mortgage and monogamy” – there was a full-fledged communist utopia, an entirely different way of existing as a society. Another world was possible, and it was fabulous.

Their achievement wasn’t just the creation of these novel sexual forms-of-life, but the making-public of living lovingly together, already there in the midst of capitalist relations. As Jarman tells it:

I was another young man corrupted and co-opted by heterosexuality, my mind still swimming about in the cesspit known as family life, subjected to a Christian love whose ugliness could shatter a mirror. I had to destroy my inheritance to face you and love you.

In this way, the gay political project wasn’t just emancipatory or messianic, nor could it be exhausted by a list of demands; from within, it undercut capitalism’s charge that there be no alternative by fucking a different world into being. The (homo)social relations on which it was predicated were not alien or radically different from any norm either: They were the simple obverse of the same drives and forces that articulated the hierarchy of men in capitalist society. Gay liberationists revealed a contradiction between male desire’s content and form, between its actual polymorphy and its public patriarchal manifestation.

Jarman touches on the truth of 20th century revolutionary movements: In the post-war period, it was gay men who constituted the most innovative and advanced revolutionary subject. Or rather, despite failing to bring about a revolution, they registered the most successes in actually living communism. In their success at forging commensurate and propulsive social forms in which theorizing lives and living theory were two fingers on the same fist, gay men and gay thought, for a brief time, inhabited that promised land praxis. Or, Jarman: “[W]hat was so exciting was meeting new people with new ideas while Heterosoc felt that all we were doing was putting cocks in each other’s mouths. Before those cocks got into our mouths we were exchanging ideas.” On the Heath, a cruising park in London (incidentally, one of the few remaining English commons), men could remap their social being in a world without hierarchy, without waiting for the revolution. In the dark, Jarman writes, “power, privilege, even good looks and certainly money” disappeared. And thus:

Fucking became a full time leisure activity. Men discovered their sexuality. The Dionysian orgy was unleashed in the park, sauna and backroom. Johnny threw himself like a dancer into the bodies, naked except for his leather jacket with its silver studs. He was just twenty-one. That night he celebrated his coming of age. That night he would refuse no-one. One after another the men fucked him, and he loved it.

Despite conforming to the famous Fourierist utopia where men would fish in the morning and suck cock in the evening, what about the gay world was so revolutionary, or even communist – especially since there was barely any thought given to the means of production? Gay praxis intervened at the level of social reproduction of the class relation itself, which had traditionally made use of male desire to produce hierarchical relations between men for the maintenance of private property. In an especially evocative passage, Jarman puts his finger on the uneasy link between these two:

At Your Own Risk recalls the landscapes you were warned off: Private Property, Trespassers will be Prosecuted; the fence you jumped, the wall you scaled, fear and elation, the guard dogs and police in the shrubbery, the byways, bylaws, do’s and don’ts, Keep Out, Danger, get lost, shadowland, pretty boys, pretty police who shoved their cocks in your face and arrested you in fear.

Male desire structures, animates, and undresses the social relations through which private property reproduces itself. In the gay life-world, however, it could be an unjealous male desire, which didn’t shy away from sharing affection with strangers. Jarman remarks that the sin of the people of Sodom was not sexual license, but lack of hospitality – they rejected God’s angels.

Unsurprisingly for the noted filmmaker, Jarman’s facility with montage is on display in At Your Own Risk. There’s a fairly devastating recitation of front-page headlines in the venal British press from the 80’s counterposed against those of a gay newspaper, where he reminds us, almost unnecessarily, that these were the same people who had waved the Nazis to victory. In another section, “Lamentations,” he mourns the dead in series, and the simple combined recollection indicts Heterosoc: “Actively or through indifference they murdered us.”

The author clearly admired Pasolini; his is the only name that enjoys repeated mention throughout the book. Salo, as he understands it, was an attempt to put the disaster of his time into film. Jarman says he never made a film with such a vocation (though one might think Jubilee could fit the bill), but that this book might be his Salo. His own disaster then would be AIDS, not simply a question of mortality at the individual level, but the devastation visited on the loving world, which he worries might not be transmissible. “I was dismayed that another generation might be denied the marvelous free-wheeling time we had. I was dismayed by those who said monogamy was the coming thing – just what we had fought against.” When he was young, “the absence of the past was a terror.” Losing the image of the past, constructed at great cost out of censure and suppression, would mean succumbing to the story Heterosoc tells of us. Indeed it seems that now, with its strenuous forgetting of the originally revolutionary-liberationist character of the gay life-world Jarman inhabited, gay politics has been co-opted and affirms what it previously defined itself against.

It is the lack of an inheritable history, the absolute groundlessness at the beginning of each individual gay life, which allows for both its inventiveness as well as its particular frailty as a lasting social form. Even the vulgar biological determinism in strains of liberal gay thought can’t account for the learning which is logically prior to a child’s articulating the social practices of gayness: on ne nait pas gay, on le devient. Because, unlike other identitarian groups, homosexuals aren’t born into their community, the retention of social memory, the maintenance of a contiguous social body over time, and the continued existence of the social forms in question can never be assured and is thus always a site of contention. The melancholic rejection of promiscuity by surviving gays in favor of a form more amenable to the social order, then, means that the revolutionary love will not be passed on to the next generation. Jarman rejects this: “I was in love with all those boys and I wasn’t going to have their passion trashed by evil people. That’s what love is about. I’m a passionate militant.”

He doesn’t despair, however. Jarman is privy to something like a secret knowledge. On the old commons at Hampstead Heath, he had come to understand the eternal now-time of orgasm, which “joins you to the past. Its timelessness becomes the brotherhood; the brethren are lovers; they extend the ‘family’. I share that sexuality. It was then, is now and will be in the future. […] we are linked in orgasm with Alcuin, St. Anselm or St. Alred, all of whom loved men physically.” Benjamin tells us, “The past carries with it a temporal index by which it is referred to redemption. There is a secret agreement between past generations and the present one. Our coming was expected on earth. Like every generation that preceded us, we have been endowed with a weak Messianic power, a power to which the past has a claim.” Jarman pleads not to let his generation, who had struggled so to bring about a new world in the image of the truth of their love, have died in vain; that we “of a better future” redeem him and prove him correct when he writes “it doesn’t matter when I die, for I have survived.” This may not quite be a promise of eternal life, but it does render the worldly fact of survival an immortal characteristic of the now-lost gay world. The final prose passage of the book cements the subtitle of the book more than the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, who canonized him for his work and because “he has a very sexy nose.” In it, he adopts the posture of a witness to truth – a martyr – delivered explicitly to future generations:

Please read the cares of the world that I have locked in these pages; and after, put this book aside and love. May you of a better future, love without a care and remember that we loved too. As the shadows closed in, the stars came out.I am in love.

Now, the careful love of marriage and the gay community’s unfaithful recollection of their past love as unthinking promiscuity remember not Jarman’s life, but only his corpse.

If there is going to be anything like a materialist gay left going forward, Jarman’s text should enjoy some pride of place, if not for the vital history he protects, then for its graceful form. An unmelancholic view of this past can take solace in the fact that its passing is precisely what endows us with messianic potentiality. Even though marriage seems to be the order of the day, queers who care about revolution might do well to affirm the right-wing fears that we will undermine the institution of the family, which is, after all, one of our goals. If we adopt the form of marriage but refuse its current content, mortgage and monogamy, can we become again a socially disruptive contradiction? Perhaps, but on the condition that we recognize ourselves as worldly representatives of oppressed fathers. Our task is to complete their liberation as well as our own.