He's an amazing creature, the modern father. Possessing in equal part confidence, creativity, endurance, optimism, passion, patience, and presence, he has thrown away the shackles of his oppressed forebears and reclaimed the prerogatives of his role. To those who doubt him, he has only one thing to say: I can do this, I will do this.

This is the modern father. No, better: the modern dad, for they are not quite the same thing. The father is authoritarian, backward-looking, distant, and uncaring, whereas the dad is authoritative — meaning that when it comes to instruction and correction he sets boundaries without punishing. He chooses instead to lead by example and with a clear mind, while in all other child-related things he gets involved, he mucks in, and most important of all, he cares.

I doubt you could find a better guide to the modern dad than Being a Great Dad for Dummies, the brain child of the three New Zealand–based entrepreneurs, Stefan Korn, Scott Lancaster, and Eric Mooij, who launched the website DIYFather.com after recognizing "the need for social innovation in the fathering space." It is on this website that you'll be able to follow what the modern dad gets up to on a day-to-day basis and be informed on the risk of having friends of the opposite sex, read daddy's rules for dating his teenage daughter, or fantasize in melancholy fashion about a world without dads. (Without dads, we are informed by the author of this piece, there would be nobody to take the sons to the games or show off daughters with pride. You get the gist.)

Absorbing as the website is, however, the guidebook is an altogether different object and fixes in time the essential qualities of dadhood in a superbly coherent and concise way. As is the case for most superheroes, Great Dad is defined by his origins — that is to say, the circumstances in which he acquired his powers. You might think that these circumstances might in some way be related to challenges presented by the women's liberation movement. Not so. Echoing a remarkably widespread rhetoric concerning modern fatherhood in the Western world, Great Dad is said instead to be the product of a "quiet" or "peaceful revolution ... among men who want to become more involved in the upbringing of their children."

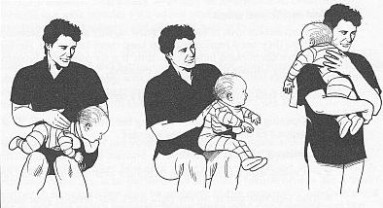

Armed with the conviction — also in no way related to feminism — that "dads can do everything mums do except give birth and breastfeed," and that "staying home looking after the kids is no longer a reason to hand in your man card," Great Dad swats aside all the misgivings of his partner and of society at large in order to answer his calling. As a matter of fact, seeing that, if anything, it is mum who holds him back — as she may "have a tendency to 'take over' and secretly or unconsciously harbor the belief that dads are somewhat inadequate when it comes to dealing with babies" — by overcoming these obstacles, perhaps even to the point of "sending mum back to the workforce," Great Dad is able to do her feminism for her. Just one of his many surprising talents.

The elision of feminism as a historical phenomenon fits within the book's benign and staggeringly under-theorized essentialism. Being inducted into the dad club means becoming nothing less than "a bona fide member of the human race, a piece in a puzzle that has been put together over millions of years," but there is no triumphalism in this statement, nor does it follow that one should practice an old-fashioned and therefore syllogistically more natural or correct brand of fatherhood. On the contrary, the book is relatively enlightened in some of its advice, notably when it comes to supporting the choices of the partner during pregnancy and labor, and in its rejection of smacking children as a legitimate form of discipline.

Great Dad is a liberal dad, in other words, and with something of the model citizen of neoliberalism, the well-adjusted, about him. More to the point, however, Great Dad's being modern and progressive is not the result of a historical process, much less the outcome of a historical conflict between different social actors. Rather it's a spontaneous coming to terms, the realization of a latent potential. Repressed for far too long by social prejudice and mum's overbearingness, the dad within is finally able to shine.

This myth of origin out of the way, a proper analysis of Being a Great Dad for Dummies would have to be based on what is and isn't written, what is and isn't included. But one would be remiss not to comment briefly on the language, which is not quite straight out of the usual style sheet for a For Dummies guide. If you get past the relentless cuteness and somehow stop yourself from hurling the book out the window after the 50th use of the phrase "your little champ," you will note a most curiously passé prudish reticence, the kind that makes the authors exclaim, on the business of getting pregnant, that "there aren't many projects in life that start with a little nooky with your best girl!" or advise, should the diminished sex after the birth be a problem, to "take cold showers and do plenty of exercise if need be." Odder still is the suggestion that in high-stress arguments with a toddler, dad may want to take a deep breath and sing a song to himself, "perhaps Incy Wincy Spider" — surely a scene that has never been played out on this planet.

There is a tendency, in other words, for this book to infantilize Great Dad, to talk down to him at the same time as he's encouraged to take on a fully adult role. But this too fits within a more important aspect of the design: namely, the fact that Being a Great Dad turns out to be a manual for early fatherhood only, up to the little champ's first day at school. But if the tantrums of a three-year-old are enough to launch Great Dad into a self-soothing rendition of Incy Wincy Spider, one might well wonder what issues might arise later on and if he has been properly briefed on how to deal with them.

More fundamentally, a preschooler poses no meaningful challenge to parental authority. It is therefore relatively easy to design a working and workable theory of fatherhood revolving around setting the kinds of boundaries that would equip a child to function amongst their peers in a playgroup or kindergarten setting — a tricky time, to be sure, but rather less challenging, in every sense of the word, than, say, adolescence. Or adulthood.

Thus even before we get to the observation that every theory of parenthood is also implicitly a theory of society, and ask what kind of social model underpins the book, we find that the theory itself is incomplete, or rather, that it is the product of its limitations: meaning not only the fact that it stops at five years of age but also that it does not conceive of families other than the nuclear kind (whether intact or broken) or of fathers except of the heterosexual variety. Utterly unsurprising omissions, these last two, if you are familiar with the genre, but which nonetheless underscore how normative and oppressive the soft, cuddly patriarchy of the Great Dad actually is.

Still, we can speculate about how Great Dad may behave with older children and reason that based on the caring model of the early years he won't be the kind of father who fires nine hollow-point 45-calibre bullets into his daughter's laptop because of something she wrote on the internet. That kind of violence — physical, psychological, existential — seems quite incompatible with the gentle prescriptions of Being a Great Dad. It probably is, but it's just not possible to be sure. Not without filling those blanks: How you go about relinquishing that early first-teacher role; how you respond to actual challenges to your authority, up to and including your daughter writing stuff about you on the internet; how you allow for possibilities other than your children being the best they can be, because personal development is not that linear or neutral, nor is it the fulfillment of a promise; finally, whom you not only help them to be but also allow them to be, is what determines the kind of father, the kind of parent you are. And in this respect, too, fatherhood as it is currently conceived, even in its more ostensibly progressive forms, is an imprint of society at large, and therefore a deeply flawed thing.