As Boeing's new planes of the future sit grounded, a visit from aircraft past and present

DC-9

Thirty-one miles northwest of Tucson, Arizona, over 100 retired commercial airliners rest in the desert, fuselages and engines in the gradual process of being scrapped, refurbished, or sealed up for uncertain futures.

The Pinal Airpark is home of Marana Aerospace Solutions, a company that acquires, stores, and services commercial airliners. They specialize in "heavy maintenance, storage and parking, component repair and overhaul, painting and exterior detail, and end-of-life solutions." The latter is particularly poignant as one roves across the terrain on Google's satellite view, gazing down at the angular rows of retired jetliners. Many of the smaller airliners, some nestled together nose-to-wing and recognizable by their occasional red tops, are McDonnell Douglas DC-9s adorned with the now obsolete livery of Northwest Airlines. This is one of the notorious airplane “boneyards” that dot the deserts of the American Southwest.

This model first flew in 1965, and the last DC-9, the 976th, was manufactured in 1982. Northwest operated these planes regularly until 2008, when the airline was absorbed by Delta and the DC-9s were decommissioned and sent to Pinal Airpark.

Zooming in and looking down from the simulated satellite camera's eye on my laptop screen, I’m confronted with the uncanny realization that I most likely spent hours in several of those aircraft now parked in the desert. I flew Northwest regularly in the late 90s and early 2000s, and recall well the near-ear thrum of the tail-mounted Pratt & Whitney JT8D turbofan engines from the farthest-to-the-back seats.

Among a host of other pragmatic advantages, the tail-mounted engines on these aircraft simplified the wing design and made the DC-9s versatile planes, able to take off and land on short runways and thereby service smaller airports as well as major hubs. These planes were attuned to geography from the outset, anticipating the range of locations that the airliner could reach. In spite of a long and fairly successful life in commercial service, the DC-9 now finds itself outmoded by newer and more efficient aircraft.

Still, the DC-9 is not quite history. Just last year, it served as the campaign plane for Vice Presidential hopeful Paul Ryan, and was visible in the background as Ryan alighted in towns across the United States, waving vigorously from the air-stairs.

"Believe in America" almost works as a slogan when we consider a family of aircraft built over 30 years ago and flown consistently, one punishing flight after another, day in and day out, and still occasionally churning the sky. Even in the face of its visible decline, as evinced in the desert layout of retired Northwest DC-9s, the aircraft’s tenacity is impressive. The DC-9 is the smaller and older cousin to the MD-80, which remains in regular service with many airlines today, and which served as Mitt Romney's own campaign plane.

The DC-9s in the desert, awaiting service or sale, exist almost at the level of abstraction: they are objects with histories, but objects which have been taken out of use, and exist, like the sculpted fragments of Shelley's Ozymandias, as indices of other times. Likewise, the Northwest Airlines logos and color schemes communicate in a sandy void a no longer extant brand, corporate semiotics rendered obsolete.

As for the actual Romney campaign planes, the particular DC-9 and MD-83 decked out with the plushest seating and promises of a better America, these planes have now been thoroughly cleaned and reconfigured by the company that leases them, Active Aero. These two planes, old and well worn, are most likely flying today—shuttling sports teams or rock bands around the globe. Meanwhile, their factory-born siblings rest in the desert, offering themselves up as spare parts and still satellite views.

737

Around the same time the first DC-9 took off, Boeing was developing the 737. This aircraft entered airline service in 1968, and will be familiar today to anyone who has flown Southwest Airlines; the 737 is the only plane model Southwest operates, and is an integral part of its corporate identity.

The most notable difference from the DC-9 is in the wing-mounted engines. If the DC-9’s tail-mounted engines were a result of geographical awareness and flexibility, the wing-mounted engines of the 737 indicate a differently grounded consciousness, a mindfulness of the maintenance required by such a transportation workhorse. These engines are easier to access and repair, suggesting a focus on keeping the aircraft in the skies as much as possible.

Unlike the DC-9, which is approaching extinction and a near archaeological status, the 737 is the most widely flown and robustly produced aircraft today, with 7283 built as of fall 2012. Another 2579 of the aircraft are on order from Boeing and in various stages of production. As if to make these numbers real, the sage Wikipedia offers this astounding factoid: “There are, on average, 1250 Boeing 737s airborne at any given time, with two departing or landing somewhere every five seconds.” Pause for a moment to imagine one of these airliners departing, and another landing; now consider this as an unceasing cycle.

Still, the 737 aircraft is not above mortal strife. The reader might well recall an incident that took place in April, 2011, when a Southwest 737 experienced a six-foot fuselage tear mid-flight, resulting in depressurization and an emergency landing. The cause was determined to be “pre-existing fatigue”—in other words, stress on the aircraft’s skin after years of grueling daily use.

A photograph snapped after the incident revealed an extra layer of intrigue:

This picture arguably reflects an interest in the materiality of the damaged plane. Yet it also suggests interest in capturing a digital image of this materiality—indeed, in capturing a digital image being captured of this materiality. The occasion was one not only for seeing how a plane is actually constructed, then, but as well for redoubling and disseminating such a view-being-taken.

Of course everything migrates online these days, so in one respect there might be nothing surprising about the Southwest 737 ceiling tear ending up as a new media bit. But we really must linger on how odd this image is: the picture is as much about taking an iPhone photo as it is about representing the damaged airliner.

As if to compound this issue, the way “The Southwest Experience” is marketed, it appears to be as much about being online as it is an experience of actual flight. Consider the airline’s info-graphic that explains how the customer/passenger is to navigate said experience:

The Boeing 737, and by metonymic extension the traveler in flight, is nestled into a new media chain of loosely affiliated object-actions: computer mouse, shopping cart, airport sign, boarding passes, 737 airliner, social media icons. The most widely flown aircraft is shown to be another mere unit of contemporary life, juxtaposed with surfing the web, disposable paper products, passing a familiar green sign on the highway, and thumbing a smartphone.

After the ceiling tear incident, the Federal Aviation Administration swiftly called for regular inspections of the lap joints on certain 737 airframes that had flown over 30,000 cycles, and a widespread crisis was averted. But I remember flying on Southwest to visit my in-laws a mere month or so after the widely reported ceiling tear: I held my then 18-month-old son on my lap as the plane lifted off the ground, vaguely wondering whether I’d be able to cling to him tightly enough in the event that the fuselage above me came undone at cruising altitude. Such in-flight paranoia aside, the 737 is not threatened by wear-and-tear so much as it risks being deemphasized (if not exactly outmoded) by a tangential, emergent sensibility, an alien notion of travel. As the Southwest Experience info-graphic insinuates by its first and last symbols, more and more, we go places on screens, too.

Dreamliner

Boeing's latest airliner, the 787, is also known as the Dreamliner. This aircraft promises larger windows, a slick new toilet with a hand-motion sensor for flushing, better air quality in the cabin—such features are all on the inside, for passengers to enjoy.

It has been called “a plane of the future,” yet on first glance it doesn’t appear all that different from things we’ve seen before. The two features most visibly different on the exterior of the aircraft are the noise-reducing chevrons on the engine nacelles, and the raked wingtips to decrease drag.

But these are subtle aspects, noticeable perhaps only to aviation geeks. Inside, the plane’s familiarity might strike one all over again: cramped seats, overhead bins, the recognizable, slouched attitude that comes with waiting to disembark or deplane...

Promotional coverage of the plane’s entry into service hyped the atmospheric improvements and minor tweaks to the Dreamliner’s passenger experience, yet the earliest images of this experience looked all too common. As if to underscore this sense, New York Times reporter Stephanie Rosenbloom put it succinctly this way: "even occasional fliers will find themselves on Dreamliners in the coming years…." A plane of the future thus flies into the friendly skies of banality.

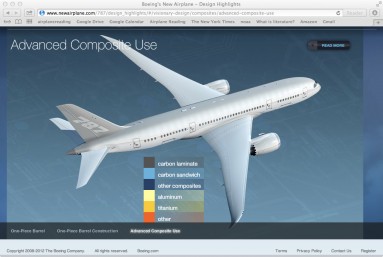

In terms of the aircraft’s design, however, the Dreamliner reimagines how an airliner's body can be made, with "one-piece composite barrel construction" that forgoes traditional aluminum skin sheets for sandwiched and bonded lightweight materials that make pressurization more efficient and cut fuel costs.

Since the aircraft entered service in late 2011, it has been plagued by minor setbacks, including electrical fires and fuel spills. These malfunctions have been called “teething problems,” as if to imply that the airplane is a living thing—indeed, an infant. Boeing has been quick to point out that all new planes have issues as they enter service, and indeed that the number of 787 problems is in fact on par with the problems the 777 had at the beginning of its life, in 1995. So if prospective passengers are alarmed by the profusion of headlines about the Dreamliner’s problems, they must also recognize that this is the fate of a new airplane in our new media ecology: No other new airliner has had to brave the viral environment of the Internet.

The Dreamliner is also a “new media” aircraft in a plainer sense, as a vessel for passenger USB ports, personal touchscreens, LED ambient lighting, and individually dimming windows. Looking deeper inside the aircraft, we find yet another familiar new media component: the lithium-ion batteries that power the aircraft’s APU or auxiliary power unit (basically an internal generator that starts the engines) as well as the cockpit’s electrical system. These batteries are the source of compounding problems for the aircraft, and as of this writing, the Dreamliner has been grounded worldwide, due to overheating batteries and the notorious specter of “smoke in the cockpit.” Lithium-ion batteries are mundane if somewhat invisible, tucked inside cell-phones and laptop computers. They charge quickly and hold a lot of juice, but they tend to overheat. Who hasn’t felt an iPhone get ridiculously hot in their pocket once or twice? This oft cited comparison reveals further the weird continuum—between wide-body airliner and handheld device—across which the Dreamliner seems to slide.

The Dreamliner represents a crisis point of sorts. It hovers between that which can be grasped, and something verging on a “hyperobject,” or a thing that is too spread out across time and space for humans to quite comprehend. The Dreamliner is an airliner like the twentieth-century DC-9, and yet it beckons us into a 21st century future of economy and efficiency. The Dreamliner promises a personal utopia of new media pleasures, bundled together with the surges and swells of consistent and collective transit lines. The Dreamliner is the same, but different.

It is still too early to know whether the Dreamliner’s battery problems will worsen, possibly becoming insurmountable and causing the aircraft to buckle as a truly innovative program; or whether the Dreamliner will grow out these teething pains and become as successful and ubiquitous as the 737 is today. By Boeing’s projected sales of 5000 Dreamliners over the next 20 years, it would seem for now that the latter will be the case. Dreamlining could become as common as, well, dreaming.

I can’t help but contemplate how first the 737s, and then the Dreamliners, too, will end up in airplane boneyards—if not soon, then some 20, 30, 40, or 50 years from now, when their systems and designs are exhausted, when we need new dreams.