The short-lived electronic subgenre witch house lingered in the emotional crawlspace beneath contemporary pop

It's been called “drag,” because it relies heavily on attenuated beats and rhythm. After that it was “haunted house.” The songs, though electronically produced, don’t recall techno but qualities bewitchingly human—as if the tracks themselves are haunted. And then, in 2009, two artists—Travis Egedy of Pictureplane and Jonathan Coward of Shams—branded themselves as “Witch House” artists. Egedy’s music was covered in Pitchfork, and the term acquired social currency. Someone went around to various music sites to tag a group of bands under the same moniker, including Salem, White Ring, and Chris Greenspan’s act, oOoOO.

From the beginning, witch house as a scene was beleaguered. Its chief artists, though collected under labels like Disaro Records in Houston, were atomized geographically and divergently inspired. All were technically in thrall to hip-hop’s “chopped and screwed” rhythms, and the same stream of adjectives—“dusky,” “slinky,” “overdosed”—flowed to describe them on the scene’s music blogs like XXJFG (20 Jazz Funk Greats, which eventually morphed into its own music label). But the bands tooled with different subject matter: White Ring and Salem with fatalism and obscure, occult mythologies, and oOoOO with distorted pop music. Each artist responded to the others’ music online, but when asked, they chafed at the name witch house. Still, they cohered to shine for a brief moment in 2010.

By March of that year, the gnats and flies were already buzzing. Live performances, reliant upon dark atmosphere, smoke screens, and extensive vocal modification, were a sham. Not even Jack Donoghue’s hair could save Salem, by then the most publicly visible of the witch-house bands, from being booed off the SXSW stage. The music, in party terms, was not good. Witch house slunk back underground.

But if these are the facts, there is another history of the subgenre that remembers why anyone liked it in the first place. It points to the most interesting acts—the subterranean ones who linger with pop and hip-hop tracks to shade in the longing gathered beneath their slick surfaces. Far from seeing witch-house artists’ reliance on the Internet as an obstacle, this alternate history highlights the acts who have made a subject of the Internet’s emotional implications.

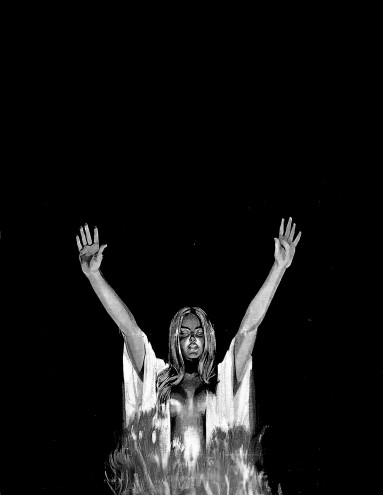

Witch house may belong in the lineage of similarly moody, involved electronic subgenres. If syrup was the backdrop for “chopped and screwed” in the early ’90s, and rave culture was the backdrop for movements like ambient house—then specters of information-age sex and relationships are that for witch house, and Greenspan’s oOoOO in particular. The name witch house has stuck to these artists because their tracks are impossible to imagine without the starved female vocals that bespeak loss and give the music its tone. They are impossible to untie from questions of gender.

Consider, for instance, Nocera’s “Summertime, Summertime” and Greenspan’s mix of the track side by side. The original is a freestyle pop tune. Its cardiac beats are relentless, its electronic brass buoyant, and Nocera’s blistering vocals shine and pirouette on pointe. The word summertime is used maybe a hundred times. On the cover of Over the Rainbow, the album on which the song appears, Nocera smiles coyly in a sailor’s cap and red patent-leather jacket. “Take me to the water,” she intones, and you can already see it sparkling.

[soundcloud id='12326006' comments='false' playerType='Mini' color='#ff7700' format='set']

Greenspan’s version (“NoSummr4u”) slows the track considerably, and Nocera’s vocals—buried in a heavy admixture of synth—shrug the weight of sunshine they carried in the first mix. But the sunshine isn’t abandoned; instead it’s mottled, recycled, and diffused through a synthesizer, which adds a scale of twinkling notes that rise and fall in pitch and places lingering emphasis on words like “maybe.” At its best, the effect creates a new space for those powerful vocals that, under Greenspan’s touch, would not only speak slower but say something different about “summertime.”

In “Summertime, Summertime,” Nocera sings:

I listen to the rain outside

Please come and take me for a ride

I really want you to come and take me far away

I want to say…

She passes from reflection (“I listen”) to entreaty (“Please come and take me”) to repeated emphasis (“I really want you to come and take me”) without missing a beat. In moments, she freewheels into more of the chorus (“Take me to the water”) and the song presses on.

In Greenspan’s take, the vocals stutter and each line echoes for effect:

I listen to the rain outside

Feel like I almost have to die—

I really want you [pause] to come and take me far away

I want to say…

In the revision, reflection threatens to halt the singer’s voice at each juncture. When she reaches for what she “wants to say,” the words aren’t at hand. As she misses her cue, mottled sun pours through the synthesizer, and it’s nearly 20 seconds before she rejoins. And when she does, instead of a beach, she seeks a nowhere—anywhere—somewhere outside the grid spelled out in the earlier pop song: “Let’s go away, let’s get away….”

In daily life, feelings of alienation like those displayed here might be assuaged by pop music’s empowered female sexuality—by Beyoncé and Kylie Minogue, who Greenspan, in an interview with the French magazine Wow, described as “like a magical thread running through the banality of life on community college campuses and at freeway off-ramps in Toyota Corollas. Like slave songs for a world where everyone thinks slavery is abolished but the people don’t know they’re slaves.”

But pop music, with its emotional sensationalism, is a shallow vessel for memory. It lives in a continuous present, making it difficult to recall the shape of the loss deplored in so many songs of breakup and pursuit, whether it be Nocera’s summer romance or Lady Gaga’s poker hand. To drag, to edit—to haunt, to linger—these are witch house’s tools. Their aim is not to sear pop’s sentiment with intellectual insight but to read into that emotion slowly.

[soundcloud id='12326028' comments='false' playerType='Mini' color='#ff7700' format='set']

Witchy tools can be applied to more than just pop music. In the original version of Three 6 Mafia’s “Late Night Tip,” the rap crew’s only woman, Gangsta Boo, is cast in two roles. In the first, she’s the female foil on hand to pout, “I need a Coach bag … I need my hair done,” so DJ Paul can throw back “Playas like me can’t be savin’ you rags.” But in a later verse that involves hard liquor, Victoria’s Secret, and a reference to Ginuwine’s “Pony,” Boo plainly embarrasses Paul and the others’ insistence that they’re “not the type that get involved in long relationships.”

Greenspan’s usual trick is to blur empowerment so it blends explicitly with longing, but here it would seem that Boo—with full intentionality or not—has already joined the two in the first take. Instead of shifting the personality of Boo’s two vocal tracks, then, Greenspan’s “CoachBagg” lays them side by side in the same dreamscape of attenuated beats. Twinned like this and absent their male counterparts, they paint a hazy picture of duplicity. But more important, that both can be sewed into one song gestures at the depth Greenspan threads across his repertoire.

[soundcloud id='12326057' comments='false' playerType='Mini' color='#ff7700' format='set']

This depth is evident in Greenspan’s wider influences. Take “Mouchette,” for instance—so named for the French director Robert Bresson’s 1967 film about a girl who comes of age in a rural French village. Mouchette, traced in black and white, proceeds from encounters with an abusive father to those with an abusive piano teacher, from a flirtatious round of bumper cars to a slap from said father who won’t let her pursue another man when she’s out at the carnival.

After her rape, the death of her mother, and her own suicide, you can feel Mouchette’s pain bodily, in your ribs and in your shoulder blades—or you might, if it weren’t for Bresson’s deflationary film techniques. The scene where Mouchette takes her life is typical: Clutching a torn white dress, she rolls down a hill and out of the frame, then into another shot and out of that one. We hear her splash in the pond, but the camera doesn’t shift until she’s beneath the surface, and then, it’s conspicuously stationary. Monteverdi plays. Mouchette is a symbol.

Greenspan’s track collapses this distance, bringing it back to the body. His “Mouchette” announces itself with strong elements of percussion that don’t land but pulse—they aren’t isolated so much as suffused through more inscrutable female vocals, which might belong to a child. And while it responds to Bresson’s deflations, it also responds to conceptions of the subgenre. If witch house is easily described as ghostly, the percussion of “Mouchette” is an attempt to reconstitute its parts so they seem more present. While Greenspan’s songs can be said to linger in case after case, “Mouchette” also seems to make a choice—to invest in Mouchette’s political, physical, and ghostly identity over Bresson’s.

The percussion is also lined with what sounds like mouse clicks. Ticking restlessly as they do, they recall tropes of the internet, of online relationships and their representation. “Mouchette,” French for “little fly,” is the same name used by Martine Neddam for her internet art project, Mouchette.org, where themes of sex and death spin from the dark fantasies of a girl who, since the site’s creation in 1996, has been “nearly 13 years old.” A number of forms littered across the Web page ask for an email address, to which “Mouchette” might send solicitous messages. Taken as a whole, it’s a strangely compelling gallery of provocations that seems to cross the thin line between information-age loss and hysteria—a reminder of what the identification Greenspan proposes with his song can easily turn into.

In “Crossed Wires,” Greenspan flies free of the bass lines that sustain his most characteristic tracks, and it’s here—on the edge of his repertoire—that things get the most “witchy.” A single female vocal sweeps back and forth, picking through bars of static before it is joined by the rich hum of entire populations of mismatched conversations. Stark piano chords prick the hum with loneliness, and the trail of the original vocal, bereft, remains.

There’s something similar in a movie script by Marguerite Duras called Le Navire Night. When the female narrator’s phone line accidentally crosses with that of an unknown man, a romance ensues over a series of similar “crossed wires.” She has a voice to which one loves to listen, he says. And then one day, he is gone and she is wounded.

The emotional universe of Greenspan’s music has a particular gravity, a particular grief that refuses to evaporate like the object of its loss has. Witch house lingers with that loss as it congeals into a place—somewhere to return to at 2 a.m., alone in front of a laptop, searching for things to relate to after a long day of alienation in an emotionless workspace.

But as witch house lingers, that loss also congeals into a gender. Beyoncé will always be the soundtrack for Friday night: friends and roommates getting together for drinks, picking out clothes for the night, and so on. Witch house suggests how to navigate the feelings sewn in between.