2009

Akron, Ohio. John has been hired to curate and organize a small collection of rare books at the university here, the centerpiece of which was the gift of a rubber industrialist, who owned much of the book collectors’ canon—a few Shakespeare folios, Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary, two first editions of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The position is tenure-tracked (which in the rules of marital chess trumps a fairly satisfying slate of adjunct work back home in Chicago—King takes Queen).

The wife will just have to find something, of course. Adjunct, adjunctive.

We live in a squat Victorian building near the university. We move in sight unseen (this has become a habit for us). The adjacent building and ours are the only apartment complexes on our rather suburban street. Backyards littered with all the paraphrenalia of childhood, as Esther Greenwood observes with a shudder in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. Children with their shattering screams. Vivien(ne)’s line added to “The Waste Land,” should be delivered in your best imitation Cockney screech: What you get married for if you don’t want children.

My office is the apartment’s solarium framed by light and windows. At first I thought, yeah, alright. A sort of writing retreat. A room of one’s own. All that. Virginia Woolf prescribed the bucolic of the country. A calm respite from the city’s hysteria. (I was so panicky all the time where we last lived, on 18th Street in Chicago, a man murdered on our street the week we moved out, children playing calmly near his chalk outline. Always our moves seem like sudden, frantic escapes, not properly considering the next because we are so anxious to remove ourselves from the former.)

I am told, rather abruptly by the head of the English department here, that I am not qualified to teach literature. Male professors with no interest in the subject teach women’s literature instead. I am reminded of my lack of a terminal degree. (Why does the idea always feel like a death?)

I find work teaching Introduction to Women’s Studies, writing SUFFRAGE on the board to bored and sometimes bemused and occasionally bitter faces. Packed classrooms. A campus diversity requirement. The university here is alarmingly Christian—a megachurch dubbed The Chapel, one of the university’s benefactors, sits on the edge of the campus. One of their ministries is a Pray Until You’re Straight program called “Bonds of Iron.” The working conditions here are much worse than in Chicago—it is illegal for part-timers to unionize in Ohio, so I have no office or even much of a communal workspace, and the pay is dismal.

As soon as we land here I begin wishing ardently to get out of this black-and-white Midwestern landscape, a town formerly industrious, now its factories sit like the vacant, rotting husks of industry. The sad Wizard of Oz window display for Christmas in one of the emptied downtown storefronts. Clark Gable once worked here in one of the tire factories—it was a step up from his father’s farm but he too left for dreams of grandeur. Who wouldn’t leave? Everyone asks: Why? About our move. The economy, you know. I mumble. A great job. (I want to really say: I DON’T FUCKING KNOW. But I don’t. I tell the mutual lie of marriage.)

The nearby Cuyahoga Valley is beautiful in its autumnal blaze. But the city itself so often Midwestern gothic. Strange sightings. The woman wandering into the Radio Shack with a half-eaten hot-dog in one hand, fingering the merchandise with the ketchup and mustard-stained other. The other woman padding down the emptied out Main Street with duct-tape over her face, clutching a Big Gulp (John observes: the kidnapped on her lunch break). We bond more intensely in our mutual dystopic vision. (Our favorite shared writer of the moment is Thomas Bernhard, when we first met it was Beckett.) A different sort of alienation than when we lived in London, or moved back to Chicago.

I am an alien here. My short cropped hair and my black Joan of Arc jacket, shiny from years of wear, the interior all torn out and replaced, a remant from our splurges on his student loans in London department stores. I feel myself stared at in the grocery store, on campus. I’m also going through a butch phase, all tight men’s jeans, perhaps a sartorial revolt from my new, more feminine role. John is stared at too with his longish hair and darling dandy vests. He does not care. Although most days I don’t even leave the house, and lounge around in what I’ve been sleeping in for days, in the blink and the glare of the outside world I do not often wear my faded and cherished articles of clothing. Except when we make regular trips to Chicago to visit my father or occasional ones to New York. I feel they would be wasted here. This wasteland.

I have become used to wearing, it seems, the constant pose of the foreigner.

Chicago now our pilgramage, which we once wanted to desperately escape. In Chicago, New York was our Moscow, like in Chekhov’s Three Sisters. It is our pattern: we forget so soon what made us want to flee, we cover it over with nostalgia, Zelda writing her novelist-husband wistfully of their honeymoon days while in the asylum. This shrine we build to our own shared origins. Viv’s shrine to Tom, once he had abandoned her, next to her framed picture of Sir Oswald Mosely, head of the British Union of Fascists. (Does every woman, really, love a fascist?)

I’ve tried to block out the local uproar dealing with Akron native LeBron James leaving the Cleveland Cavaliers. I’ve always found it pernicious, how those in the Midwest criminalize those who leave, like it is some rejection of their own lives. Unlike the ambivalence towards their now-prodigal son, rock musician Chrissie Hynde of the 80s group The Pretenders is a much loved celebrity here. “Chrissie” this. “Chrissie” that. The vegan Italian comfort food restaurant she owns in town has become our culinary sanctuary.

As a girl I remember reading an interview with Chrissie Hynde in Rolling Stone about how she left this city in Ohio when she was young and moved to London. I remember thinking of her as this example of what I could do myself one day. That I could leave Chicago, leave the family, leave the Midwest. And I did. For a little bit. But now I am back here. The eternal return. (To write, perhaps, is to always return.)

So many of the gods of modernism hailed from the Midwest. Scott Fitzgerald from St. Paul. Ezra Pound fired from the college in Indiana. Tom Eliot of the lofty Eliots of St. Louis. And they all escaped, to Europe—they became expatriate, cosmopolitan. They managed to shed their origins, their Midwestern skin. Hemingway years earlier attended the same high school in Oak Park, Illinois as my father and his siblings. God, I idolized Hemingway when I was in journalism school. Now I hate his guts because of how he demonized Zelda in his memoir A Moveable Feast. And for how he treated his wife Hadley. She, summarily dismissed.

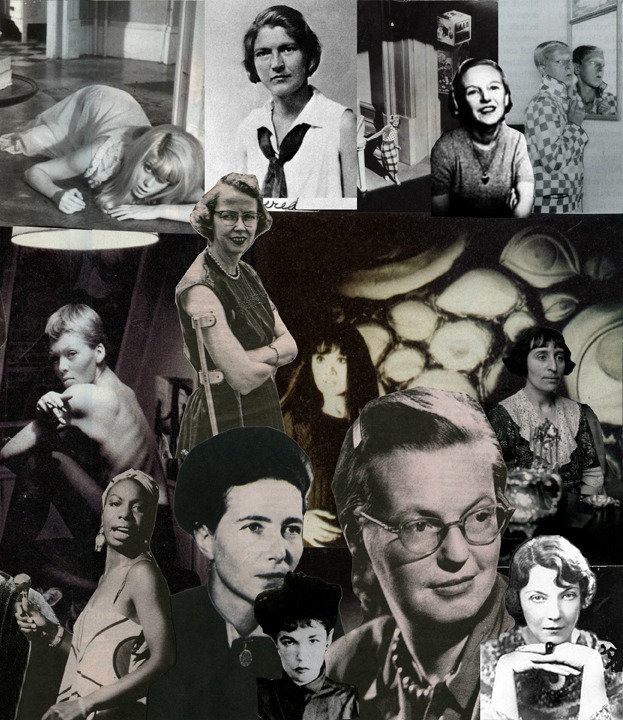

(I am now in another union. It is a union of forgotten or erased wives. I pay my dues daily.)

In Cleveland the local bibiliophilic society explicitly prohibits women from joining. John attended a meeting at the invitation of his colleague at Oberlin (I was not happy.) One of those quasi-secret societies of rich white men with bizarre rituals, held in some grand Victorian home. The series of tableaux that begin Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, her treatise on the material conditions that could allow a women to write, to write well. Her scenes illuminating women being banned from the grounds and libraries and luncheons of the fictional college Oxbridge, to show that a woman of her time would be banned from all the public space of reflection and socialization and higher learning that Woolf argues is important in order to begin to have the interior space to roam about in, to think the lucid thoughts that foster Great Texts.

This sort of segregation is familiar to literary modernism, with their cliques and societies. The most famous one being Gertrude Stein’s salon at 27 Rue de Fleurus. Stein would hang out with Hemingway and Fitzgerald, while Alice B. Toklas in the next room would make small talk with the wives. Gertrude Stein ventriloquizing Alice in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (with any sense of irony to the inequality? I don’t know): She speaks to the greats, while I talked to the wives and mistresses.

Oh, but the stories they have to tell.

***

Of course since we’ve moved here I’ve been rereading Madame Bovary. I am Madame Bovary as I read Madame Bovary. Ennui, excess of emotions. C’est moi. I am Zelda, I am Vivien(ne). Zelda and Vivien(ne) both bored in their new lives as women married to the literary prophets of their generations. Both suffering from Madame Bovary’s disease until other, more ominous ones were diagnosed and even more ominously treated. “Vivien was still in poor health, and suffered from nervous headaches and sleeplessness—no doubt aggravated by the fact that, while her husband was actively and continually engaged in work of some kind, she had very little to do and was becoming bored.”

God, it’s boring here. Stuck in the provinces. The novelist Jean Rhys’ bungalow in Cornwall where she spent her exile, for years and years in poverty and obscurity writing her heroine in Wide Sargasso Sea, rewriting the madwoman Bertha Mason in Jane Eyre. “All the dullest books ever written have ended their lives here,” she wrote in a letter to her daughter.

I must get as far away as possible. Must escape stagnancy, miserabilism. Yet I am here, frozen. I am afflicted with Eliot’s aboulie. I know I want to leave this stale town as soon as possible. I am sure if I do not I will die.

I think of Madame Bovary —“She longed to travel, or to go back and live in the convent. She wanted both to die and to live in Paris.”

I begin rereading the journals of Anaïs Nin, both the abbreviated ones that she published during her lifetime, and then the ones with all of the fucking (which I prefer of course). In the narrative Anaïs weaves over countless journals, she is a liberated woman who finally escapes the oppression of her provincial environment. In her version she leaves out Hugo, her banker-husband who supports her. Apparently, according to Nin’s biographer, all the American housewives who first read Nin’s journals felt they were given permission to leave their marriages, but then felt betrayed when they learned the truth.

I suppose I could take John out of this accounting entirely—but then who would believe that I was in Akron by choice?

Living here I develop a desire to be analyzed, probably because of all the Anaïs Nin I’ve been reading, Nin who had an affair with her analyst Otto Rank, who wrote a book on the artist. Perhaps this is a desire to be interpreted like a literary character. I leave a message for the Cleveland Center of Psychoanalysis. I begin to toy with the idea of training to be a psychoanalyst, and I will become a feminist analyst to tortured, eccentric artists. Like Julia Kristeva. Sylvia Plath who considered a Ph.D. in psychology.

A woman at the Center calls me back and I change my mind and never return her call. (I realize the costly sessions would be daily, I have not yet figured out the 40-minute drive, refuse to drive anywhere, here, in fact.)

***

I wake up and read although Nietzsche says that’s foolish. A sort of narcotic, reading. I read with my hands down the front of my pants— my mode of reading is masturbatory. Sometimes I feel guilty about my lubed fingers all over library books.

Reading Anaïs Nin’s diaries and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer in tandem makes me want to have affairs, despite, or maybe because of, the intensity of my love for John—how I once idealized the apparently open marriages of modernism, the triangulation of Anaïs, Henry and June, the free love of Bloomsbury, the Bowles who shared everything except their beds.

(In London, the temptation of an angel-faced philosophy student.)

I too want to have a sensual awakening outside of marrriage, like Emma or Edna Pontellier in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening. Wifedom a possession. I don’t want to be possessed. I want to be free. Like Charlotte Brontë projecting onto her heroine Jane Eyre her desire for experience, as Virginia Woolf critiques in A Room of One’s Own—except instead of wanting to travel the world, reading these books I temporaily want to fuck the world—a literary nymphomania.

Because of the mythical lothario conjured up in Nin’s journals, I’ve always fantasized about having an affair with Henry Miller, horndog Henry Miller, who can’t keep his hands off me, who will back me over a couch and go at me, who will fuck me so I stay fucked.

In Paris during the second leg of the Bowles’ honeymoon, Jane goes out alone at night, prowling the streets, the lesbian bars. Jane Bowles who loved to slum like Baudelaire, like Vivien Leigh channeling Blanche DuBois. Outside of one club a homeless-looking man propositions her nightly. Some time later she sees the man’s picture in the books section of the newspaper. Her forgotten man in the back alley—Henry Miller.

I begin to compulsively read historical romances as research for a novel, featuring a housewife named Emma who inhales historical romances to numb herself. For days in a daze I can’t read anything except these romance novels. (I prefer Regency romances, costume dramas, like Jane Austen with fucking.) I suddenly become allergic to anything more highbrow. I watch TV on my computer during the day when I am supposed to be writing, my favorites are teen soap operas. I ghost fan forums endlessly analyzing character motivation as well as “shipping” certain characters, short for “relationshipping,” everyone so passionate about the characters that just know are destined to be together.

We are invited over to the house of two history professors for Thanksgiving. We can’t eat most of the food because we eat a vegan diet, and I’ve also been having terrible digestive problems. They have made four types of cranberry dressing. It’s the only thing we can eat and they blink expectantly at us. One has tequila in it. I lick my spoon tremulously and think of Emma licking the bottom of her glass as Charles falls deep within it. There is a young man there, a jazz pianist with soulful eyes. I realize he might be their pot dealer. I find myself mildly flirting with him. My stomach cramps up. I am bowed over. He could be my Leon I muse absent-mindedly.

Did Tom foist Bertrand Russell on Vivien(ne), to give her something to do?

Here, I am the wife of. That is how I am introduced by others. Not a writer. A wife. (No one seems to care that I am a writer, awaiting the publication of a slim, nervous novella.) Everyone much more fascinated with John’s career. In his dungeon office John is surrounded by piles of leatherbound volumes, books that look burned, in several languages, a Babylon. Eliot studying languages while at Lloyd’s bank. I love seeing John finger a book and read its leaves, soothsay it, speak its secret history. He can lapse into the charming pedant so easily. My Professor X, as Woolf calls the patriarchs of higher learning in Room. Vivien(ne) sitting in on Tom’s classes on Victorian literature he taught for working-class adults. Her expression rapt, worshipful. She sacrificed everything for him, for his eventual genius.

I am realizing you become a wife, despite the mutual attempt at an egalitarian partnership, once you agree to move for him. You are placed into the feminine role—you play the pawn. Once you let that tornado take you away into the self-abnegating state of wifedom. Which I did from the beginning, now almost a decade ago, quitting my job as an editor of an alt-weekly so we could live in London and he could attend a graduate program in the history of the book.

I write this book of shadow histories. These histories of books’ shadows.