In Virginia Lee Burton’s classic children’s book Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, burrowing is a way of settling into the ground, not taming it

AS a kid I loved Virginia Lee Burton’s book Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel for its simplicity: Its hero, Mike Mulligan, spends one whole day digging a hole to save his life. Unlike the real-life men I knew who dug, Mike doesn’t care about horizons or wives or beer, or anything but his work. Best, the book’s tone tells us that if Mike can do this work, everything will end well—happily, even. Reading it offered me a simple, true relief. I never fantasized about my wedding day. Like Mike, I just wanted a job that made me happy and gave me a home.

In the book, Mike and his steam-shovel friend, Mary Anne, have spent a whole life traveling and working together, until new technologies threatened to make them obsolete. Stuck but not wanting to chuck his darling into the scrap heap, Mike hatches a practical but theatrical plan: The new town hall in Popperville needs a cellar, and Mike promises that he and Mary Anne can dig it in a day. He doesn’t sign a contract or plan anything beforehand; he just makes a promise like a kid crossing his heart on the playground. And because Mike and Mary Anne “always work faster and better / when someone is watching us,” the whole town comes out to stare. It was an entirely new strategy to me back then: If you’re stuck, just dig.

I loved Mike Mulligan too because when Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby starts kindergarten, her teacher reads this story to the class and Ramona asks, But when did Mike Mulligan use the bathroom? This guy digs and digs while the sun climbs to noon, faster and faster with no bathrooms anywhere, let alone a private corner. That was the first time I thought about work in a narrative, and bodies, and bodies and narratives locked in time. (Also capital letters as noise and speed. In the hole, Mike and Mary Anne go “BING! BANG! CRASH! SLAM! / LOUDER AND LOUDER, / FASTER AND FASTER.”)

But first times aren’t always important. Maybe what’s important isn’t that Mike was the first, but that I was really young. Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel is in the children’s corner of many doctors’ waiting rooms and almost every Barnes and Noble children’s section. It’s everywhere, and it’s beautiful and secretly weird and, especially for a book featuring a steam shovel with eyeballs, hearteningly nonmagical. Girls are told to read it, and boys, and my one friend who used to identify as a fire engine. Most significantly, Mike Mulligan was the first story I read where the hero digs himself a home: where he burrows to maintain and stay gold instead of climbing or conquering or some other penis-shaped thing.

Mike is a hero with one face, and his victory is believing in that face. It’s a solid message, made truer through its simplicity, yet much more complicated than say, Mike Mulligan and His Big Dream. Burton saw children as collaborators—as generators—in a more immediate way than contemporaries like The Carrot Seed’s Ruth Kraus, who would bring notebooks into schools to copy down what children said. Though both women saw deep wisdom in children and children’s literature, and both women wrote books I love fiercely and tenderly (and maybe you do too), Kraus seems to see herself as an interloper, an anthropologist, whereas Burton actually entered into conversation. In part this was because she was anxious about the value of her work, especially in the lonely early stages of a new book, but more pragmatically, the kids just made her stories better, and she worked better working with them.

One of my favorite photos of Burton is of her on a lawn full of children in 1964. She stands in the middle of everyone in bare feet, a striped skirt, and a light wide-neck blouse. Not only are the kids almost all straight enrapt, but this rapture appears in many different expressions on their faces. One girl has her eyes closed. Another looks at the grass, one finger in her mouth. Burton knew that good stories need different entry points for different brains, and perhaps casting a net this widely is a kind of digging too. It’s certainly given her books life across multiple generations.

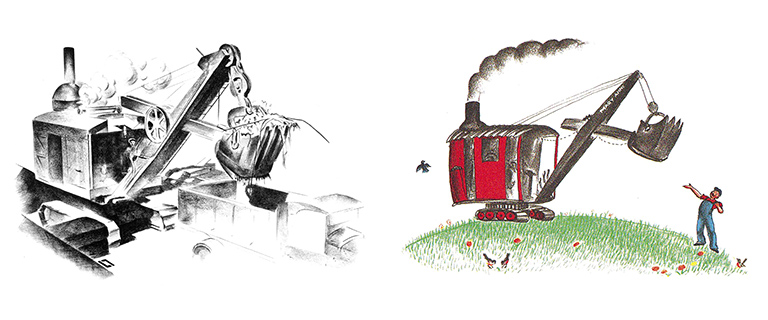

Mike Mulligan begins arrow-like: “Mike Mulligan had a steam shovel, / a beautiful red steam shovel.” I’m quoting it as poetry because Burton wrote it like that. Music and space were crucially important to her, a dancer who wrote by filling the corner of the barn where she worked with a maelstrom of sketches and technical diagrams. Even her teaching style was a circular, nonbinary system focusing primarily on changing gradients and proportions. (Just like comics do, though Burton actually hated the funnies, and wrote Calico the Wonder Horse (or the Saga of Stewy Stinker) to dissuade her kids from reading them.) Mike Mulligan is told with sweeping but even line and tone across almost 50 pages, all punctuated and anchored by Mary Anne’s red, particularly the parts where everyone else is shadowed in soot and dirt. When work gets sparse, advertising appears in all-black caps on Mary Anne’s back: “MIKE MULLIGAN / DIG / ANYTHING / ANY TIME / ANY PLACE.”

Most likely, Mary Anne’s name is a slant version of Marion Steam Shovels, a company founded by Henry Barnhart, Edward Huber (of revolving-hay-rake fame), and George W. King in Marion, Ohio, in the late 1800s. Marion built heavy equipment for construction and mining, and twice, crawler-transporters for NASA. The company set multiple world records for moving cubic feet of earth in a specific time frame, thanks in part, it advertised, to the solid iron rods supporting its shovels’ booms. In 1997 the company folded, and split its paper archive between Bowling Green’s Historical Construction Equipment Association and the Marion County Historical Society. In a way, its story is the macro version of Mike Mulligan’s story, only more tragic because even new technologies or a sympathetic illustrator couldn’t save it. The entire company became obsolete. That Mike and Mary Anne went ghost.

On the other hand, throughout Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel Mike is proud of this steam shovel he owns. The cover shows Mary Anne bursting, grinning, through a banner like a super goofy sports-team mascot. Burton’s illustrations virtually always place her at the center, surrounded by sun and robins and looking solidly at Mike. She is alive but dedicated and owned, and she works: “He always said that she could dig as much in a day / as a hundred men could dig in a week.” Charmingly, Mike has never actually checked this but he’s pretty sure it’s true. Their relationship is more essential than romance—it’s a happiness from having solid worth and purpose across a lifetime. Mary Anne is elegant and functional, and her presence in Mike’s life gives him purpose too. They “dig together.” They get it. Their relationship isn’t sexual, though it is definitely loving. Plus “Mike Mulligan took such good care / of Mary Anne / she never grew old.” I remember being terrified by this, as a child. If she doesn’t grow old, can she still learn? Will she die young? Will she rust up when Mike dies, or will he live forever too? (The latter seemed unlikely, as, again, for all Mike Mulligan’s illustrations, the reader never doubts his world is ours too.) All told, Mike Mulligan is probably the first time I read about a man taking care and a woman’s purpose making her ageless. One of these stories is still fairly rare, the other near omnipresent. I wish for a sequel where Mary Anne is a crone, maybe friends with smudged-up toasters and old fried electric blankets.

The illustrations in Mike Mulligan are all of work, of digging, in such bird’s-eye detail that all people become the same size and occasionally Mary Anne loses facial expression. Burton, who founded and led the all-female Folly Cove Designers group in Gloucester, Massachusetts, practiced and taught drawing with three tenets—“subject, sizes, tones”—all components present in this work, which came early on in her publishing career. The diplomas she handed out to graduating Folly Cove students showed a woman triumphantly printing a question mark in sequential frames. These are still on display at the Cape Ann Museum, which is near Our Lady of Good Voyage Church, whose Marian statue holds a ship and shows up in T.S. Eliot’s “Dry Salvages.” (My favorite intersection in the town is Spring Street, a one-way, and Fears Court.) Together, Mike and Mary Anne dig canals, tunnels, highways, landing fields, and cellars for skyscrapers. Sometimes people stop to watch and again, when they do Mike claims the digging happens faster and better.

When people watch, they mix and meet: the selectmen, the constable, the postman, the telegraph boy, the milkman, the milkman’s horse. By holing up and digging, Mike and Mary Anne are making a stage in reverse. All these people are defined solely by their work too, save Mrs. McGillicuddy, though her husband never appears and she is wearing the best outfit: a pretty ruby dress with pockets. These illustrations in particular are perhaps in dialogue with Burton’s life as a professional dancer and aquarium keeper, because nobody talks but they do walk and they shift. Movement is primary, but not as character development. Because if these characters don’t move, they become sad and sit and freeze. They become not-themselves. If Mike and Mary Anne don’t move, there is no story. They must keep digging.

Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel was Burton’s third book, published in 1939, two years after Choo Choo, the story of a train engine. Her first story, Jonnifer Lint, was about a piece of dust. After Jonnifer was rejected by 13 publishers, Burton got the manuscript back and read it to her son Aris, who fell asleep before she could finish. From then on Burton drew and told stories for children—usually her own, Aris and Mike—expressly to give them what they liked and wanted. “Children are very frank critics,” she said, but they are also eager and open-minded collaborators, for the most part. Burton shared a birthday with her son Mike, who also shared his name with this book, his face—he’s the little yellow-haired boy with “good ideas”—and later, with Aris, the copyright. (Today Mike manages amusement parks in California and China, including Marine World/Africa USA—now a Six Flags—and Intra-Asia.) Plus there is the awesomely weird footnote on page 39, where Burton acknowledges her young neighbor Dickie Birkenbush, who solved the book’s ending at dinner one night. Mike can stay in the cellar and be the janitor, and Mary Anne can be the furnace! (This was the first time I saw a footnote too.)

But all this movement and collaboration doesn’t mean Mike Mulligan can’t hit direct emotional notes. When after all these years of digging holes and passageways and fields, there is no more work for Mike and Mary Anne to do, Burton shows how bad it is through purple earth and capital letters and two lines of tears falling from Mary Anne’s steel face. The issue, dramatically, isn’t that Mary Anne and Mike are less professional or even that “the new gasoline shovels / and the new electric shovels / and the new Diesel motor shovels” are more efficient, but that new technology “took all the jobs away.” Burton never really explains this in text or image, though the new shovels have sad-looking eyes and mountain-shaped-mouths. Nobody seems particularly stoked on the change. Without jobs, Mike and Mary Anne can’t move and so they don’t exist. “No one wanted them anymore.” And in turn, they don’t want to transform or expand, or retire, or hire new shovels, or anything. They just want to work. To dig.

Burton dug, too. She found her home and so her seven (eight, counting the Jonnifer-dust) books are rooted there, most spectacularly her last, Life Story, which includes everything from the actual apple tree outside the house she shared with Mike and Aris and her husband, George Demetrios, to sea creatures and dinosaurs. Most neatly, to me, she’s not cute about any of it: Admittedly her characters are pretty much all children or coupled-up adults, but also Burton writes about female snow shovels and dipper sticks and trip lines. She believes people can change and live full lives inside the four walls where they make home and space for others. On the one hand this is fairly typical “women’s work,” yet still Burton subverts because she’s so democratic about it. In Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, everyone has work and purpose and feelings, and the moment comes not when someone changes roles but after they’ve successfully completed their job.

Final happiness arrives not when a new relationship is solidified or new discovery made, but when the characters literally get to sit peacefully in a hole and chill. Sometimes the little boy comes over for stories, or the selectman comes over for stories, or Mrs. McGillicuddy in her ruby dress will bring a pie. Otherwise Mike and Mary Anne just heat the hall and read. This kind of freedom is antithetical to what I’ve been taught over and over again, and so the book ends not only happily but questioningly: What if, instead of transformation or fire or constant reinvention, we just dig a home and make sure it’s warm and private and welcoming? What then?