Given the choice between being white or being black, how could you possibly choose either?

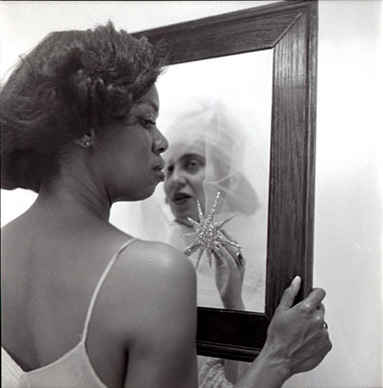

Carrie Mae Weems’s Mirror Mirror shows a black woman looking into a mirror where a white woman appears. The subtitle reads: “Looking into the mirror, the black woman asked, ‘Mirror mirror on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all?’ The mirror says, ‘Snow White, you black bitch, and don’t you forget it!!!’”

Helen Oyeyemi’s fourth novel, Boy, Snow, Bird, also returns to the old German fairy tale Snow White—a story about a girl so white they named her after it—to critique anti-blackness. In the original Snow White, a queen accidentally pricks her finger while sewing, and, contrasting the drop of blood on her finger with the snow outside the window, wishes for a daughter with lips red as blood, hair black as the ebony window-frame, and skin white as snow. She dies giving birth to the child she wished for: Snow White. The king remarries, and the new queen’s magic mirror helpfully lets her know that her stepdaughter is more beautiful than her. She tries to have the child killed, but Snow White escapes and takes refuge with a household of dwarfs (those same seven dwarfs immortalized by Disney as a fraternity of cheerful workers, and by Donald Barthelme as a kind of dysfunctional Maoist sect kept alive by sexual jealousy—Oyeyemi wisely elides them). Snow White’s stepmother tracks her down and tricks her into eating a poisoned apple. Finding Snow White in a coma, the dwarfs assume she is dead, and place her in a glass coffin. A passing prince falls in love with her beautiful corpse and persuades the dwarfs to give him the body; Snow White wakes up; the necrophiliac prince proposes marriage; and at their wedding party Snow White’s evil stepmother is forced to dance to death in a pair of burning shoes. That’s the Brothers Grimm original: Like all fairy tales, it’s both satisfying and horrible, rich with sex and death.

Oyeyemi takes this tale and refashions it to talk about race, the social form that mediates between sex and death, tells us who should be loved and who can be killed. Boy, Snow, Bird is set in a small town in New England in the 1950s. A white girl named Boy is raised in New York by her abusive father, a creepy figure who exterminates rats for a living and whose parenting mainly takes the form of intricate acts of violence. She escapes to the comparative paradise of Flax Hill, where white people ply interesting trades like making elaborate cakes or selling antique books. There she meets a handsome, widowed jewelry maker who dotes on his daughter, a dazzling little girl called Snow. Boy marries him and has a child she names Bird.

The surprising brown skin of this second daughter reveals the secret of Boy’s husband’s family: They are white-passing blacks from the South. Therefore snow-white Snow is black too; most of what has appeared white through the first part of the novel now turns out to be either black or predicated on blackness. Boy is white but she catches on quickly: The beauty of whiteness, embodied by Snow’s semblance of it, is a threat to her daughter’s happiness. Through the efforts of Boy, in the role of ‘evil stepmother’, the half-sisters do not live not the lives that might have been determined by their respective appearances. White-seeming Snow is raised by her black aunt and uncle, and black Bird grows up with her white mother and white-passing father. Already in this brief description it’s evident how much pressure Oyeyemi’s magically charming novel exerts on the categories of race.

The characters are sharply drawn and likeable, making the calculated sweetness of Oyeyemi’s telling more complex on the palate. Boy narrates the first half of the novel, where race appears only obliquely. She’s a great invention, witty, tough, and loving, and Oyeyemi has fun with her hardboiled diction. Later on, she switches to the point of view of Bird, a well-loved and inquisitive kid whose attempts to make sense of race and her relation to it stage Oyeyemi’s concerns. The pleasure of the prose is in a kind of seductive sleight of hand—amid the surface shimmer, what Oyeyemi is really interested in, broadly, is how patriarchy and white supremacy warp lives like wishes and curses do in fairy tales. In place of the drop of blood shed in the original Snow White, all the novel’s characters live in the shadow of the “one-drop rule” with which American apartheid policed the fluctuating boundaries of whiteness, a vision of race-as-bloodline that endures to this day.

Despite their separation, when long-lost sisters Bird and Snow rediscover each other, they find that they have some unusual things in common: “I don’t always show up in mirrors, either,” Snow confesses. “For years I wondered if it’s all right or not, but there’s been no one to ask, so I’ve decided that I feel all right about it.” Both girls are as unreflected in the mirror as they are unreflected, in different ways, in the crude categories of race. When Snow goes to a bar with black friends, a stranger mistakes her for white, asking why a girl like her is hanging out with them, and she falls into self-protective silence. Meanwhile, Bird grows up among white people and must search for images of blackness. Race shadows the characters, but because of its insubstantiality it can’t grab hold of them. A plot twist towards the end of the book suggests that gender, too, is unstable and at heart immaterial. Race and gender, like money and magic, are “real abstractions,” figments given substance by belief and experience.

According to the Jamaican theorist Sylvia Wynter, as the west became secular, race supplanted faith as the new, ostensibly scientific answer to the question of what it meant to be human. Whiteness—in opposition to its antithesis, blackness—became the basis of European identity, operating as a retrospective justification for European exploitation of the rest of the world. What is race? At heart, it’s an empty place, a pretext. Yet it must be filled with content: cultural habits, physical attributes, aptitudes, and so on. The conceptual incoherence of race is advantageous to white supremacy, as the benefits of whiteness can be extended or retracted pretty much expediently. This is how Jewish people, for example, once considered a subhuman burden on European civilization, have survived to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with their newfound white brothers in the fight against brown Muslims. One cannot live the truth of race, because it has no truth, but we all live its terrible emptiness.

Anti-blackness and white supremacy are co-constitutive, as Oyeyemi sketches out with remarkable gentleness. The US, founded on the innovative concept of the secular state, drew on a racial rather than religious model of birthright to make use of the barbaric free inputs of slavery. If whiteness was how Europeans reinvented colonial pillage as racial destiny, then America is where this “rational” anti-blackness reinvented itself as national culture. The blog Stuff White People Like, for example, ironically posits everything from tattoos to bottled water as the paradigmatic tastes of white America, but what white people really like best of all is this: not being black. Blackness and whiteness circle each other in an unevenly lethal dance of mutual mis/recognition.

Value, as Marx noted, only appears to inhere in things; in reality, it must be extracted, either from nature or from proletarian lives. Similarly, race-authenticity does not spring up from the mere fact of certain physical features—it has to be mined from others. Mixed-race identities are fissured only in relation to the lie of integral blackness or whiteness. Still more problematically, white beauty needs its frame of black ugliness, a structural flaw that reveals its guilty origins. Adorno read the original Snow White as a longing for death: “The queen… gazes into the snow through the window and wishes for her daughter in terms of the lifeless, animated beauty of the snow-flakes, the black sorrow of the window-frame, the stab of bleeding; and then dying in childbirth.” Whiteness is always framed by black sorrow, and its purported beauty is a scandal that Boy is right to try to protect her daughter from. “Snow’s beauty is all the more precious… because it’s a trick,” she concludes. “When whites look at her, they don’t get whatever fleeting, ugly impressions so many of us get when we see a colored girl—we don’t see a colored girl standing there… I can only… begin to measure the difference between being seen as colored and being seen as Snow. What can I do for my daughter?” She sends Snow away.

The logic of race renders even apparently wholesome abstractions like love or beauty white supremacist. The slavers’ gaze still informs white visions of black women, who are widely represented as dumb, angry, fleshy, fertile, and strong; no coincidence, then, that the beauty of white women is the inversion of this, founded on charm, purity, and delicacy. The US-inflected racial categorizations of porn suggest how deeply embedded race (with its logic of visibility, of public spheres) is in that supposedly most private space, sexual desire. The ontological scaffolding of race also holds up sexuality, not simply as preference (for similarity or difference) but as its ground. How else are we to recognize ourselves, if fucking is self-recognition, self-authentication? The churn of Western sexual politics has always required an exotic outside against which to test and rediscover itself. When the white world had reason to celebrate chastity, people of color were imagined as sexual savages; now that whites have discovered erotic pleasure as good health, they have invented a non-white world full of genital mutilators, sexual oppressors, and homophobes. Without the energizing illogic of race, whites, like pandas, might die of their lack of interest in each other. Yet in Boy, Snow, Bird the pill is sweetened by that cute title, by fairy tale and a happy ending. Bird and Snow learn to love other despite Snow’s problematic beauty. The evil stepmother turns out to be good after all. When a magically animated American flag traps Bird, it turns out all it wants to do is kiss her. And yet the form of the fairy tale suits, because lived experiences of racialization themselves lack realism, though not reality—even in real life, race unfolds like fate out of accidents of birth.

When Snow’s aunt shows her a map of the US and tries to explain racist legislation, the girl flinches: “I thought that if I accepted what Aunt Clara was saying, then that map would apply to me, that map with the hideous borders… So I grabbed both her hands and smiled at her, to try to get her to go along with me, and I said, ‘No, no, don’t say that about me. That’s awful. It can’t be true.’” I think every child who finds herself suspended between multiple forms of racialization knows this urge to turn away from an ambivalent destiny—a betrayal for which, like Snow, many of us struggle to forgive ourselves, although others, like Bird, learn to laugh instead. But we are always betraying someone. Given the choice between whiteness and blackness, how do you choose blackness, when even a child already knows that it is generally synonymous with ugliness and stupidity among the whites who arbitrate our lives? Given the choice between whiteness and blackness, how do you choose whiteness, when any child can already tell that whites are the agents of the darkness that they insist we introject?

Race marks the weight of history, or the portion of it you have to bear. Snow is beloved not because white skin is inherently beautiful—beauty is just as socially determined as morality, with which it is often subtly twinned—but because whiteness, like new snow, wants to disavow its birth in blood and dirt and present itself as a clean slate on which history-as-progress can be written. But in a partisan world full of mess, shame, love, joy, pain, Oyeyemi persuades us, we should be suspicious of anything that finds itself beautiful in the image of neutrality.