An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

An audio version of this essay is available to subscribers, provided by curio.io.

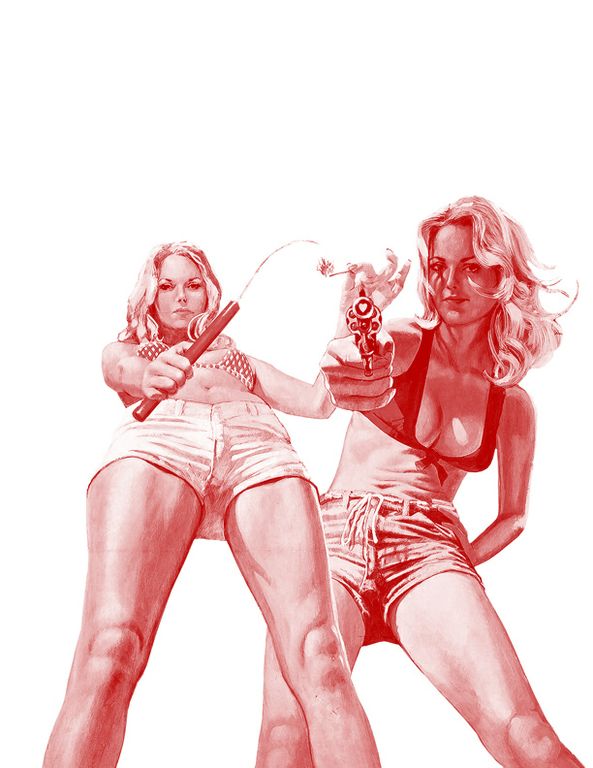

Every love story is a cop story

True love story

Despite appearances, it’s hard to believe that the police really see climate activism as a serious threat to the state. And yet before the London Olympics there were bureaucrats on record saying that the threat of terrorism was now less disturbing to managerial dreams than that of “protest.” The massed warships on the Thames were meant for the threat within, not the marked outsider. Thus vaguely defined, the state’s new nightmares must also however implausibly include dreadlocked hippies, in the image of which K, our hero, shaped his new life, wild-haired, in carnival clothes, full of fervor and concern.

K’s eyes squint from photographs; his consciousness of their asymmetry is revealed in how he repeatedly finds pretexts to hide one eye. In a picture displaying the injuries he sustained when his (disavowed) colleagues attacked a protest camp, he holds one exemplary hand in front of his face so that it obscures the one straying eye, the one always looking elsewhere. Afterwards, when everything has been revealed, the asymmetric eyes belong to a former cop; they are ostensibly the same, but like the spectral quality of the loved one’s beauty diminishes at the same rate as love, it doesn’t signify anything any more: his new face is clean of features.

Watching footage of undercover cops passing miraculously through police lines at a big demonstration, this porosity the only sign of their betrayal, I think how hard it must be for one cop to fail to recognize another: muscles must contort with the effort of not nodding hello. But that pales in comparison to the effort it must take to fall in love without the use of your real name.

And how did this become a story about love? Because the lovers of K are suing the police: They entered into their various relationships with K unaware that he was not K. And K is suing the police because the police did not stop K, their employee, from falling in love in the course of his duties.

Etiology

Symptoms of love: firstly, the catastrophic inability to distinguish between love and lust, between observation and omen, between necessity and contingency. Later, the sense that it is provocative for the beloved to walk down the street, in the aura of his beauty; anything could happen in this dangerous situation. Feelings of disorientation. Feeling the duty to invent a new language in which to describe the beloved, inevitably getting stuck in the customary language, the conjunction of the worn-out old language and the unformed but necessary new language producing hideous mutations, purple prose. Wetness, slipperiness, not just in the anatomically predictable places but in the edges between one thing and another thing, this new edgeless conception of things making the vowels looser, the joints looser, loosening also any vestigial respect for “private property.” Leaving shops with your pockets full of free jewelry, with which to decorate yourself for the beloved. Or, under duress and for similar reasons, buying new clothes.

Formal subsumption of love. The figure of the incognito recurs in romantic comedy, the fake lover, the lover in disguise; the practical joke, the elaborate trick, scenarios in which the trickster’s confidence becomes a weak spot, a gap in the clouds through which a real love appears in the guise of a fake. We find the rom-com’s mythic origin in Elizabethan drama, but these comedies of mistaken identity and role reversal predate the full institutionalization of love, or perhaps they arise at or prepare the fusion between courtly love and family life.

Romeo and Juliet, cop and activist, German village girl and American GI, Soviet spy and British spy, man and woman. These loves are banned and celebrated because they simultaneously rupture boundaries and reveal a secret homogeneity. Famously, in Romeo and Juliet, transgressive love demonstrates that proper names (and their attendant categories) are both contingent and determinate; they have no “real meaning”, but nevertheless they form the iron pattern of a life. You felt that you could easily have been someone else, but you were not.

In his lover’s arms, K is momentarily thankful for his and his employers’ expansive interpretation of what is required to gain intelligence, to become intelligent, to make circumstances intelligible. It is not K’s fault that his intelligence might not be admissible in court. K’s face is familiar, K smiles from across the room, it’s as if you’ve seen him before, as if he’s absolutely alien, absolutely familiar. It’s as if there’s something inside K that is not K, some kernel of K within K that you have to search for and not find.

In occupied buildings, on the street, in dismantled camps, K is beaten by the cops. K’s bruised hands seem more bruised than other hands, because more loved. But K’s bruised hands, when you look back, are like a mask; the hands are a ruse to cover his bad eye.

1960s-optimistic interpretation: the police are against love, and the evidence is that one of them wants to be prevented from falling in love. Everyone knows, for example, the letters and speeches in which Himmler talked about his struggle to overcome his feelings of compassion and empathy – the strategy of the police, like the strategy of fascism, is to overcome natural human feelings. If K had let himself really fall in love, he might have become a traitor to his class of origin and really joined the community of which he pretended to be a part. (Has anyone ever researched the number of soldiers who gave up their posts after a hippy gave them a flower? Perhaps even one soldier, one flower, would be enough to support a humanistic theory of human transformation.)

Contemporary-nihilist interpretation: there are no “natural human feelings,” no Eden of feelings, no garden we’ve got to get back to. “They say it is love, we say it is unwaged work.” We are most surveilled, most policed, where we believe ourselves most free: in the zone of intimacy.

Modes of substitution

Real subsumption of love. From 1957 until 1963, in order to establish a “science of love,” Harry Harlow embarked on his famous monkey experiments. Baby rhesus monkeys were taken away from their mothers a few hours after birth and raised by a team of lab workers, through the medium of two parent-substitutes, a “wire mother” who gave milk, and a tactile, snuggly “cloth mother”, a rectangular object covered in soft material. The baby monkeys vastly preferred the cloth mother to the wire mother, against the prevailing theory in American psychology at the time, which imagined love as “drive reduction” – you love whatever reduces your hunger, thirst, discomfort, etc. Harlow’s challenge to science: surely there’s more to love than proximity? He announced that his system of deprivations had laid the ground for a true science of love. Later, he had to admit to some experimental errors, as all the monkeys raised by cloth mothers grew up to be insane, unable to form attachments to other monkeys. The “fake” mother had not successfully synthesized the “real” mother. By it effects, the substitute gave itself away.

The first baby monkeys in the experiment were born prematurely and the researchers had not had time to create a face for the substitute mother’s smooth, round head. When they tried to modify their mistake – giving the “mother” two eyes, a line-drawn mouth – the baby became distressed by the incognito, repeatedly turning around the head, back to the smooth and featureless expanse of the first face. The first image of love is the most authentic, not because of any depth or particular significance, but because it was the first. It is valueless, beloved even if useless, and impossible to exchange. But its radiant blankness fixes deathlessly in place all subsequent mechanisms of value.

Harlow, with the madness of capitalism, was able to totally re-imagine human relations (why not a machine as a mother?) while at the same time positing them as natural (deducible from the behavior of monkeys). Although he wanted to make an experimental critique of drive reduction (a concept born in the 1930s and 40s, an era of general reduction, when life all across the world was being reduced, reduced), he ended up with a concept of love almost as schematic as one motivated by drives. The love he imagined is an amalgam of functions: feeding, touching, holding. He speculated that, in the future, men or even machines could perform these functions just as well as women, and that childcare might become an optional pastime for the rich. The thesis verges on the wildest techno-visions of Marxist-feminism—factory-womb, mother-bot—but it is not feminist in tone, intention, or most of all in its complete misunderstanding of reproductive work. Women continue to look after children, because this continues to be economically efficient, even economically constitutive.

The mother does not have to be a “real” mother in the sense that it gave birth to you, is a woman, or is related to you, but it has to be one person, present and attentive; it has to be someone who holds you; it has to not be a team of scientists or a cop. It has to be “real,” real as in, “I’m here and I know who you are.” It has to do its work with pleasure.

Is K a sex worker? He fucks for money, but the money is mediated by another form of work. The end of bourgeois marriage, in present social conditions, has only brought about a generalization of prostitution, as Marx predicted. Now the shop assistant must offer her joy by the hour, the receptionist’s smile is a measurable grace, and the cop masquerades as a lover.

K and the women

Thesis: insofar as it involves gender, which it has to, all love (in capitalism) also involves a cop.

Women are those to whom men lie. The more privileged your position, the more lies you can expect to be told. The wife’s peace of mind is in perfect, unknowing counterbalance with the anxiety of the mistress, for example. The beloved woman is the one to whom the man lies most, best, longest, and love’s hidden abode of production is the massed ranks of the frankly unlovable, who know very well what their true condition is. To take seriously the commonplace that gender is a relation of domination not in its specific articulations (not every particular man towards every particular woman) but in its totality, we have to say that, insofar as you are loved as a woman, you are loved as a captive. But perhaps all this sufficiently explains is the enduring popularity of, say, stiletto heels, or The Story of O.

The thing in which everyone is interested (sex, love, women) must be at the same time the thing in which no one is interested. Still, somehow everything I write is from love, or desire, a desire that is a confusion of affiliations, like Bataille imagined the sea “liquefying” like a pussy and “continually jerking off ” at the same time. But K, a lover against love, brings the evidentiary into the field of the gestural. Why did you look at me like that, so confidentially, in a room full of lawyers? Why did you put your hand so close to mine?

We wanted to be tough and unsentimental, but we couldn’t let go even of the word, we couldn’t stop clutching at it, the corners of the L and the V and the spikes of the E cutting into our palms, blood pooling at the centre of the O. Either it (love) was the blandishments of culture seducing us, Robert Pattinson seducing us, Katy Perry seducing us, away from our true purpose of transformation, or it (love) was the true kernel of the world that we would eventually arrive at, once we’d broken it apart. Either it (love) was a prefiguration or a red herring, either it was a Trojan horse against us or it was us inside the Trojan horse. For a while, dizzy, I stopped saying “love” and would only use the gerund, loving, loving, thinking by this replacement to smuggle in permanence under the counterfeit of constant activity. I envied K his talent for intimacy.

“I love you” can’t be a lie, really, because it’s not a claim about truth. The terms are always shifting. And yet eventually it has to become contractual; broken promises are broken contracts in which the injured party has no rights. And holding sway over everything, a tyranny against multiple tyrannies, the hypothetical promise of the womb: What if K had had a child?

Well-worn lessons of K: the police are everywhere, not least the bedroom, most of all the bedroom; what is most private is most public, and love is most private, most public of all. Mark K is the institution of marriage miniaturized and transformed into a technology of surveillance, like the standing army becomes the drone. The police have long counterfeited love, because they hate all unofficial secrecy. And yet it seems we will have to go on fighting on mad and hypothetical grounds such as “love,” “specificity,” “beauty,” exactly where we’re weakest, where most complicit, most likely to fail.

Comments are closed.