While coverage of the riot grrrl movement inadvertently domesticated blunt female rage, Juliana Hatfield honed the critical edge of ambivalence, but her exploration of ugly feelings has disappeared her from the canonical alternative-rock narrative.

The year 1992 was “the year of the woman” in the political arena, or so journalists claimed. Women gained an unprecedented number

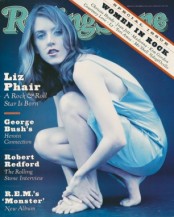

Women had long been making challenging rock music, but only for this span of years could you find Liz Phair crouched in a slip on the cover of Rolling Stone, beckoning readers to open its 1994 special issue on women in rock,

or a sneering Fiona Apple as the emblem of Spin’s 1997 “Girl Issue,” or a New York Times music critic naming 1996 the era of the “Angry Young Woman,” singular.Of all the miniaturizing labels attached to female musicians in the 1990s, angry and empowered hardly seem the worst offenders. But it’s worth asking why the history of women in rock music is so often told as a narrative of confrontation and empowerment, when other emotional rubrics beckon. Why do we canonize female anger, and not female confusion or longing?

In the fall of 1991, a 24-year-old Juliana Hatfield had just broken up her college band, Blake Babies, a mainstay of Boston’s fertile indie rock scene, and finished recording her solo debut, Hey Babe, now many years out of print. It came out on the independent label Mammoth in March 1992 amid the industry gold rush that followed the success of Nirvana’s Nevermind, and was among the most successful independent releases of the “year of the woman,” selling over 60,000 copies and earning widespread critical accolades. Critics praised Hatfield’s ear for power-pop hooks and delighted in her tortured introspection, frequently commenting on her “babyish” vocal timbre as though it were an affectation or a marketing ploy.

Hatfield was swiftly signed to a major label, and her time in the media limelight over the next few years — a spot on the Reality Bites soundtrack; a guest-starring role on My So-Called Life; several magazine covers; an ambiguous relationship with Lemonheads front man Evan Dando — made her a central figure in the early ’90s alternative zeitgeist. Yet even though Hey Babe helped catalyze the “women in rock” era, it has been all too easy to forget the album’s foundational role in this genealogy — indeed, to forget Juliana Hatfield’s name altogether. In part, this stems from her distance from the riot grrrl movement, whose epicenters were in D.C. and Olympia, Washington, far from Hatfield’s hometown of Boston. Canonical riot grrrl bands like Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy, Huggy Bear, and Bratmobile married the personal and the political in incendiary punk music that took on explicitly feminist themes: rape, incest, patriarchal oppression, gender and sexuality, female friendship and solidarity.

Riot grrrl bands crafted a collective mythology that pulled individual listeners into an imagined community larger than themselves. To be alone in your bedroom with Bikini Kill’s Pussy Whipped is already to have been drafted into a girl army. By contrast, Hatfield resisted being incorporated into any community larger than one. “There is no archetype of a female loner-by-choice, especially in the pop-rock music world,” she writes in her 2008 memoir, When I Grow Up.

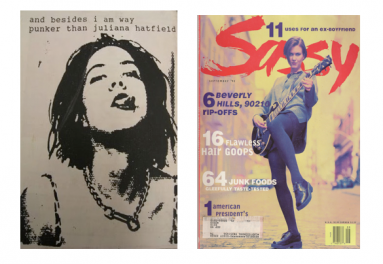

Hatfield’s story, in many ways, ran counter to riot grrrl’s narrative. Early on, she made a number of comments that brushed against the grain of ’90s empowerment discourse: She declined to identify with feminism, wagered that females were genetically inferior guitar players to males (though hoped she would be counted among the exceptions to the rule), and professed to a journalist from Interview that she was a virgin in her mid-20s. Around the time that Hatfield landed on the September 1992 cover of Sassy magazine — purveyor of indie culture to the young female masses — riot grrrls were calling for a total blackout of the mainstream media, whose reportage, they believed, was distorting and trivializing the movement. In 1994, Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna would position Hatfield alongside Evan Dando as an emblem of rock-and-roll banality in a self-published zine called My Life With Evan Dando, Popstar. Physically beautiful and politically neutral, a symbol of empty celebrity and false ideals of artistic transcendence, Dando figures as a kind of “cardboard cutout” that blinds women to their own genius and distracts them from their true enemies. The back cover reads, “besides I am way punker than Juliana Hatfield.” And even though this declaration is part of the zine’s surrealist performance project and not a manifesto, it still drew a line in the sand that persists to this day.

The riot grrrl movement still casts a long shadow over contemporary female musicians, reflecting not just its ongoing significance but also the impoverished critical vocabulary available to address women as complex and multifaceted artists. (Lindsay Zoladz takes up this subject in her 2011 Pitchfork article, “Not Every Girl is a Riot Grrrl.”) Part of the magic of the movement was the framework of empowerment it offered young women, but when outside commentators began using “anger” and “empowerment” as the sole explanatory lens for women’s music, these concepts calcified into stereotypes. “The nineties was about the normalization of female rage,” Marisa Meltzer points out in her 2010 book Girl Power.

Prizing straightforward expressions of rage above all other emotions and using that to guide historiography of women's music undervalues the criticality of more muddled feelings. A telos of “empowerment” veers all too easily into reflexive judgment of female art that is more ambiguous, less directional. The personal, the emotional, have a history all their own.

***

From even before Hey Babe was released, Hatfield herself wanted nothing to do with it anymore. As she took stock of the 11 songs — emotionally raw, sung in an unabashed soprano, more pop than the fuzzed-out, Dinosaur Jr.–inflected rock she had envisioned — she felt no sense of triumphant accomplishment. Instead her eyes welled with tears. She was overcome with mortification and shame. Just who the hell was this person? It seemed a cruel joke that an album with a title intended to channel the boyish swagger of J. Mascis and Lou Reed should instead come off as wimpy and diaristic — and so female.

By 1996, she had long since ceased playing songs from Hey Babe in her live shows. She renounced the record at every turn. “It makes me want to cringe. It just sounds sappy,” she explained to a journalist in 1993. “I think I need to get less personal and more cryptic, ’cause I embarrass myself a lot,” she told another.

The qualities Hatfield hated most about Hey Babe — that quirky, childlike voice, the vulnerability and fragility of the songs, the deep self-loathing they evinced and therefore seemed to forgive in their hearers — were the things I would connect to most strongly. When I first encountered the album in 1996 at the age of 13, it struck me as a concept album on longing and insecurity, each song analyzing a different dimension of the desire to speak, to find a self, to be recognized as a self, delivered in a voice that skidded from soaring, girlish wail to a kind of shattered mumble, not much more than a whisper. She vacillated between viciousness (“There’s a lump in my throat that won’t go away / I’m gonna rip it out!”) and resignation (“My tiny screams don’t make a sound / ‘Cause I’m ugly with a capital U”). She built entire worlds out of the state of feeling small.

Hey Babe’s landscape of feelings — self-disgust, second-guessing, depression, cautious optimism — have no place in a reception model that hinged strictly on “empowerment.” If Hey Babe’s tone of general malcontent has endeared the album to alienated listeners over the past 21 years, it has also kept the album from wider recognition. This reflects our cultural preference for “vehement passions” over “minor feelings.” As theorist Sianne Ngai notes of the Western literary tradition, “something about the cultural canon itself seems to prefer higher passions and emotions — as if minor or ugly feelings were not only incapable of producing ‘major’ works, but somehow disabled the works they do drive from acquiring canonical distinction.” This explains a lot about Hatfield’s disappearance from the alternative rock narrative.

Yet there is strength in Hatfield’s willingness to engage the push and pull of confession, the urge to tell and to withhold. Hatfield’s voice is sweet, high, almost impossibly luscious; it wobbles on a dime and cracks when pressed. She sings phrases so wordy they leave her gulping for breath, as though she can scarcely keep up with her thoughts and feelings, but these long lines reflect the state of feeling silent, contained, and small. The most up-tempo songs are usually the most thematically excruciating, plumbing depths of obsession and codependency: “Why are all those other people always saying things about me? I’m not a loser, I’m just lonely,” Hatfield sings in the bouncy “I See You.” In “Forever Baby,” the key shifts progressively higher and higher, going off the rails in its desperation to stay connected before breaking abruptly into the next track, “Ugly,” an acoustic instruction manual on living with low self-esteem. “I’m pretty lost but I don’t want to be found / My tiny screams don’t make a sound,” she sings, chillingly matter-of-fact.

To make confessional art about the feeling that your “tiny screams don’t make a sound” is to revise the meaning of self-expression altogether. The silent scream, the open wound-confessional who can’t communicate with others, the frankly gorgeous young woman who sings of being loved by almost everyone but also about being ugly are affective contradictions at the core of Hatfield’s legacy. Hey Babe reverberates in the space of not rising above, and owning up to it. “Ugly feelings,” Ngai contends in her 2005 book Ugly Feelings, are those negative but ultimately weak emotions that do not lead to action, including envy, irritation, and paranoia. Ugly feelings never culminate in catharsis, which makes them especially adept at diagnosing social conditions in which action too is blocked, like powerlessness and frustration. Irritation deferred rather than anger purged. Hey Babe bypasses the vehemence of anger, jealousy, and fear to engage with the struggle to connect and be heard, the condition of being suspended between alienation and attachment.

And yet there was power in the way Hatfield remained both emotionally labile and meticulous as she measured the distance between the self and another person, who held out the promise of recognition without ever fulfilling it. The only thing that approximated fulfillment in these songs was the music itself. At the brink of suicidal ideation, Hatfield would turn a corner: “Here comes the song I love so much / Makes me wanna go fuck shit up / I got Nirvana in my head / I’m so glad I’m not dead.” The idea of music as a resource for the solitary fuckup seemed precisely the point of Hey Babe. All the better, I would come to believe, that these lonely songs, so true to the emotional landscape of female coming of age, felt like my own secret possession.

When you say that you “relate to” a song, generally that means it conjures a flash of self-recognition, essentially backward-looking (I have been there and felt this!). The song’s prescience about you feels uncanny, even magical. But connecting to music can also involve a much stranger model of cathexis. I had felt awkward and alone, for sure — nothing too serious — but as I fell into the habit of listening to Juliana Hatfield day-in and day-out, I began to think about her songs not so much as a reflection of things I had felt or experienced already but as a script for the kind of person I might yet become. Hatfield’s songs weren’t aspirational in any obvious way. They were all about feeling shy, rejected, obsessive, silent, ugly, and powerless. They were a permission slip to grow up ambivalent, inward, messy. Still, it was a conscious decision to anoint Hey Babe the sonic bible of my coming of age.

Unlike traditional Bildungsromans — which depict their (typically male) heroes overcoming emotional and social losses to achieve a unified, agential adult self — Hey Babe holds out the possibility of finding strength in the condition of weakness. It portrays coming of age not in terms of claiming power but rather as a process of navigating ongoing crises of attachment: to a love object who treats her shabbily (yes, it’s Evan Dando); to a social world that offers few pleasures; to a sense of self constantly and painfully in flux. The album aestheticizes powerlessness, dredging up the dolor of female coming of age without glamorizing it or resolving any of its emotional complexity. By the end of the album’s final song, “No Answer,” the narrator jumps into a car and leaves town in a culmination of sorts, but she offers no promise of self-actualization. If there is a quest narrative at work in the album, it's ongoing and introspective, non-teleological. (Hatfield would name her next album Become What You Are.)

Would similar words describe the narrative of adolescent fandom? As a teenager, I was desperate to meet the artists I loved and to find a point of entry into their world. I sent a lot of handwritten fan mail and skipped a lot of school to go to shows hours from my hometown, where cool things rarely seemed to happen, as is the way of hometowns everywhere. In 2001, I managed to get a job at Fort Apache, the recording studio and artist management company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Hatfield recorded several of her albums, Hey Babe among them. It was nothing short of a revelation for me to have willed myself into actual relationships with the people who had shown me what kind of person I might be able to become, or had become — it was all mixed up by then.

It probably comes as no surprise that my affinity for Hey Babe, an album so fixated on the seeming impossibility of connection, would inspire me to reach out to Juliana Hatfield. Tons of people reached out to her. I remember her two-tiered pile of fan mail (“good/normal” in one box, “weirdos/don’t give to Juliana” stacked in another). I got to see her at the studio all the time. She would drop by with Betty, her yellow Labrador Retriever, in tow, all black eyeliner and small smiles, to talk to her manager Gary Smith or to pick something up. When I recorded one of my own songs there before heading off to college, her band members backed me up on bass, drums, and keyboards while she nodded supportively from the sidelines.

“It’s so confessional, and this is stuff that I never talk about with anyone,” Hatfield says about Hey Babe now. “I couldn’t talk about my feelings. I couldn’t recognize my feelings in myself. I couldn’t identify my feelings as feelings. When I wrote about them, it was a way for me to name feelings that I didn’t really understand.” And isn’t the transparency of fandom its own kind of humiliating exposure?