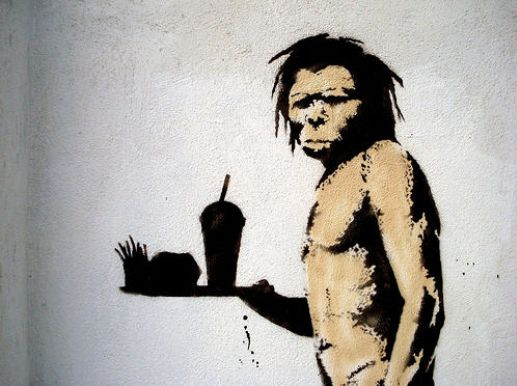

How do you make a food fad appeal to libertarians? Invoke human nature.

Every dietary preference has its corresponding political stereotype. Vegans are to Ralph Nader as meat-and-potatoes types are to Dubya. Artisanal pickle-loving hipsters gravitate towards the Obamas, and anti-soda activists have a friend in Mike Bloomberg, at least for now. Omnivores, though seemingly agnostic, are split into two camps: those who will truly eat anything, and those who will eat anything so long as it contains organic ingredients their grandmother could pronounce.

Then there are those who are concerned not with their grandmother, but their great-great-grandmother’s ancestral state of nature. Where does the Paleo diet fit in the politico-foodie spectrum?

Proponents of the Paleo, or Caveman, diet believe that to achieve optimal health, we ought to subsist off of foods that were available to our Pleistocene-era forebears. The Paleo philosophy rests on the notion that humans adapted to vastly different circumstances than the ones they live under today — that before the relatively recent shift to an agriculture, industry- and internet-based society, we lived for millennia as hunter-gatherers, and did so without the current very high levels of cancer, diabetes, or heart disease. For Paleos, the primal lifestyle is our true state of nature — our blueprint, as one advocate puts it — and we must mimic it as best we can.

In practical terms, living like a caveman typically means shunning all sugar, save a dab of (raw) honey or an occasional piece of fruit, and banishing grains and beans in favor of vegetables, meat, fish, and poultry. White potatoes aren’t recommended, but yams are fine and dietary fats, including the maligned saturated kind, are upheld as the holy grail of nutrition. Milk is high on the Paleo blacklist, but butter, on the other hand, is encouraged. Nuts are acceptable, but don’t even think about peanuts — they’re actually legumes. Bacon occupies a sacred space on the plate of the Paleo dieter.

The trend is, for the most part, food-based, though the principles are sometimes applied to childbirth and parenting, exercise and fitness, and mental and emotional health. Some Paleo acolytes forgo shampoo; others complain about the “unnaturalness” of antibiotics, hormonal birth control, or monogamy. Judging from various Paleo forums online, homeschooling is fairly popular, as are hairy men, eating with one’s hands, and exercise that mimics the Primal life: running barefoot (or with fancy five-fingered shoes); lifting heavy rocks; avoiding “chronic cardio,” also known as distance running; and practicing sprints, even in the absence of pre-historic leopards.

Grok, a 30-year-old hunter-gatherer, is upheld by marksdailyapple.com, a leading Paleo site, as a Paleo a role model. Grok, a caveman composite, is “simultaneously his own person/personality (incidentally male) and an inclusive, non-gendered representative of all our beloved primal ancestors.” He’s “a likeable fellow” who has a “strong, resourceful wife and two healthy children.” By modern standards, Grok “would be the pinnacle of physiological vigor . . . a tall, strapping man: lean, ripped, agile, even big-brained (by modern comparison)” with “low/no systemic inflammation, low insulin and blood glucose readings, healthy (i.e. ideally functional) cholesterol and triglyceride levels.”

Grok is healthy because he has relatively low stress levels and subsists on what nature designed him to eat: “Wild seeds, grasses, and indigenous nut varieties,” seasonal vegetables, roots, berries, meats and fish, small animals, and big game. Chasing animals made him a “solid, nimble sprinter”; foraging gave him “impressive physical endurance” and lifting beasts made him “tough and burly.”

***

Given the semi-mythical position of imaginary Groks in the Paleo world, it’s easy to accuse the modern cavemen of inconsistencies. How prehistoric is it to be living in condos, ordering grass-fed steaks from FreshDirect, enjoying heat and hot water, and sharing recipes online? The irony is not lost on Paleo advocates themselves — and, to be fair, if they shed their clothes and took to the woods they’d only be mocked the more for it. Charges of hypocrisy, however amusing, are facile. Paleo is an improvement on a diet of processed, sugary junk. It’s not the first diet to banish starches, and it certainly won’t be the last. In fact, by any other name, the Paleo diet would be just that — a diet.

But more substantial problems lurk in the reasoning behind Paleo principles. By assuming that all that was once natural is now good, militant Paleo leans on biological determinism to back up its theories. While it may not advocate for a complete reversion to cave-dwelling, it accepts that we evolved in a certain way to do certain things and not others, and that advances in technology, civilization, and culture can do little to change that. This logic, however seductive, is incomplete. You can’t get an ought from a was.

There’s evidence that the “was” is vastly oversimplified, too. Marlene Zuk, a biologist at U.C. Riverside, appraises the Paleo lifestyle in Paleofantasy: What Evolution Really Tells us about Sex, Diet, and How We Live (Norton, March 2013). Zuk notes that even if the good old days were, in fact, good, there was no singular primal lifestyle or even period for us to mimic. And while it’s true that humans existed for hundreds of thousands of years before forming societies around agriculture, that doesn’t mean we’ve been wholly unable to adapt to the so-called ravages of modern life. Rather, the time that has passed since the shift towards agriculture — about 9,000 years, though estimates can vary — has provided our bodies with ample time to adapt to diets that include grains and dairy. “What we are able to eat and thrive on depends on our more than 30 million years of history as primates,” writes Zuk, “not on a single arbitrarily more recent moment in time.”

A key example of this kind of adaptation can be found in our ability to consume dairy. A great many people in the world cannot digest milk, but there are nonetheless some lactose “persistent” individuals who can. Their ability to do so, writes Zuck, is a result of lactose persistence being passed along through natural selection. “People able to drink milk without gastrointestinal disturbance passed on their genes at a higher rate than did the lactose-intolerant, and the gene for lactase persistence spread quickly in Europe,” Zuk writes, citing research that suggests this took place over just 7,000 years — “the blink of an evolutionary eye.” What this shows is that humans can adapt over the course of a few thousand years to better absorb whatever nutrition is readily available to them — on a farm, for instance, or in a herding society.

Human adaptability doesn’t end there, though. When the genes aren’t passed on, other bodily functions step in: One example is the gut bacteria found in some Somalis that aided in their digestion of dairy, even though they lacked the gene normally associated with lactose persistence. And when all else fails, civilization comes in and ferments the milk to create yogurt or cheese — more easily digestible forms of dairy — that a greater number of people can consume. We even thought of Lactaid — lactose persistence in pill form.

Illustrations like these help Zuk undermine the Paleo assumption that we are not made for these times. “Consumption of dairy exquisitely illustrates the ongoing nature of evolution, in humans as in other living things,” she writes. “Our ancestors had different diets, and almost certainly different gut flora, than we have. We continue to evolve with our internal menagerie of microorganisms just as we did with our cattle, and they with us.”

That isn’t to say we’ve adapted perfectly — but according to Zuk, the idea of being perfectly adapted to any environment is a myth unto itself: “Paleofantasies call to mind a time when everything about us — body, mind, and behavior — was in sync with the environment...but no such time existed. We and every other living thing have always lurched along in evolutionary time, with the inevitable trade-offs that are a hallmark of life.”

***

The Paleo preoccupation with what’s “natural” has even more troubling implications. Incomplete or flawed interpretations of our biology have long been used to marginalize women, racial groups, even entire civilizations, and nutrition may well become the next variant in this pattern of discrimination. If rice isn’t “natural,” does that make those entire continents with highly developed cultures who eat it “un-natural”? Doesn’t agriculture, however flawed it may be in certain societies, support billions of people? Let’s not forget that for centuries women were considered ineligible to participate in most professions, sports, and diversions on the basis of their supposed female “nature.” Are modern bread-eaters somehow less human than those carrying out “primal” urges by sprinting, lifting, and eating meat?

These troubling questions are probably not the point of an apparently well-meaning lifestyle program. Many adopters of the Paleo diet do so for no reason other than weight loss, or vanity, or ailments caused by certain foods; others are simply curious about how so-called “ancestral” nutrition will affect them, or how certain types of foods affect their bodies. If their giddy testimonials are to be believed, the Paleo diet can cure everything from diabetes to anxiety attacks, which sounds wonderful. Still, the social and political implications of Paleo reasoning ought to be more closely examined, especially as the lifestyle gains adherents.

Paleo’s main proponents aren’t particularly partisan. Mark Sisson, who keeps the Paleo blog MarksDailyApple.com, says on his page that “people’s health and personal enjoyment of life matter more to me than politics and the hot air from the latest pundits.” But Libertarians have embraced the caveman set as kindred spirits, and it would appear that the caveman lifestyle and anti-state, laissez-faire tendencies often come hand in hand. Paleo-Libertarian logic maintains that the U.S. government is to blame for obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and dozens of other ills by virtue of telling us to eat the state-subsidized fruits of Big Agriculture’s labor. It says the USDA’s nutrition guidelines were created with the food lobby, not the human body, in mind.

These are by no means implausible or even particularly radical claims. Some socialists and environmentalists have come to the same conclusions, at least nutritionally speaking. Still, this admittedly healthy distrust of government — not to mention the adoption of a diet that is the complete antithesis of the USDA’s recommendations — is innately libertarian. Gary Taubes, a science writer best known for his anti-sugar crusades, is widely cited in Paleo circles. When Reason magazine asked him why so many libertarians are drawn towards Paleo, Taubes responded that perhaps they simply “like the idea that government agencies and federal agencies can be just dead wrong.”

Some true believers take the “natural” argument even further by asserting that the centralized state, and all of its freedom-thwarting attributes, are a consequence of a grain-based agricultural society. The low-fi libertarian website LewRockwell.com features pages upon pages of articles about the Paleo lifestyle written in a rugged, conspiratorial tone. “It came to me like a revelation on my morning commute: Bread is a tool of the state,” writes one commentator. “The ‘staff of life,’ the very symbol of food itself, has become to me a symbol of the domestication of humankind. It has also suggested one more way I can work to strengthen the individual and weaken the state.”

Another article, written by a young man named TobanWiebe who advocates for “Paleo-Libertarian integration,” bore the rallying cry, “No grains, no government.” “Paleo and libertarianism share a common bond in individualism,” Wiebe writes. “Both value personal responsibility and oppose government paternalism, wanting nothing from the government except to be left alone. Both recognize that nothing good can come from using the political means to further their cause.” Wiebe goes on to argue for the importance of “Misean longevity” for the Libertarian cause and to mourn the grain-fed demise of his idols: “It saddens paleo-libertarians that Murray Rothbard was struck down by a disease of civilization at the young age of 68. It is important that libertarians do their best to avoid such a fate — the libertarian cause is too important.”

In October, the site’s founder Lew Rockwell himself observed the growing popularity of Paleo among younger Libertarians on the campaign trail. “When I spoke at the two Ron Paul events in Tampa, a young man kind enough to pick me up at the airport told me a fascinating story. The vast majority of young Ron volunteers in offices he visited all over the country were paleo. If a kid ordered pizza — which was always the primary or perhaps only campaign food — he was practically booed,” reads his blog.

The Libertarian-Paleo link makes a lot of sense. As Mr. Wiebe points out, changing one’s diet is in almost every case an act of personal responsibility. Although some evidence suggests that non-food factors like BPA, high fructose corn syrup, and other chemicals contribute to cancer, diabetes and other “diseases of civilization,” it’s easy to frame many fat-related ailments as a failure of the will. An individual’s failure to act rationally, argue Paleo-Libertarians, is exacerbated by the government’s tendency to thwart free enterprise in the health and agricultural sectors, and limit the boundaries of our knowledge when it comes to diet and nutrition.

The Paleo-Libertarian alliance saw these arguments play out in a legal context last May when the Board of Dietetics/Nutrition of North Carolina told an advice blogger and life coach with diabetes that he could not dispense pro-Paleo diet advice online without the proper certifications, even though bloggers with diet advice are a dime a dozen on the Internet. The blogger, Steve Cooksey, alleged that this was a violation of free speech. His case was thrown out in August; Libertarians and Paleos alike were very upset.

With all of its contested conclusions and shaky methodologies, nutrition is a controversial science. It’s also convenient outlet for those who believe in self-reliance to shun the government’s prescriptions, blame the less healthy for their predicament, and offer unsolicited advice on bootstrapping oneself into a smaller dress size. What could be better, from a Libertarian perspective, than to alter one’s lifestyle from a government-sanctioned model to one guided by enlightened, evolutionary, natural principles that match the primal, anarchic state of man?

***

Primal human impulses are a convenient and, on the surface, logical way to explain our most mysterious attributes. (Why do we like crunchy things? Is it because we used to snack on insects? Are Cheetos a surrogate for crickets?) And it’s no surprise that the rise of Paleo coincides with the popularization of evolutionary psychology, and also “natural” birth, parenting, education, and so on. The world today is as baffling as ever, and a quick look at today’s headlines — cannibal cops, urban chicken warfare, CIA love triangles — strongly suggests that we’re closer to our caveman ancestors, at least intellectually, than we’d like to admit.

Is it worth exploring our how our ancestors lived to inform further research about what best suits us? Certainly. But, much like our environmental adaptability, our knowledge of our distant ancestors is constantly changing — and at an increasingly rapid pace. Consider the research into gender roles in caveman societies: Rather than having what we today would consider stereotypically stone-aged divisions of labor, Paleolithic humans actually seemed to live in a relatively equal society. The men did not, as a matter of course, go out to hunt game, and women did not stay home foraging and lactating.

“Saying you want to maintain your wife and children on [big-game hunting] is the ancestral equivalent of claiming that you will be able to fulfill your familial responsibility on the proceeds of playing lead guitar in a band,” Zuk points out, adding that when meat did come in, it was often shared among non-kin — an early form of distributive justice. According to one anthropologist that Zuk cites, there’s evidence that across all cultures, women did everything that men did, with the exception of metalwork. “The paleofantasy of the cavewoman staying home with the kids while the caveman went out for meat,” Zuk concludes, “would have ended up with no one getting enough to eat.”

The jury is still out on what exactly Paleo-era humans even ate. The variety of foods seems to be broadening — lots of Paleo eaters see tubers as kosher, and a subset of Paleos called lacto-paleos even accept dairy as a compatible source of nutrition. There are some Paleo-curious bloggers, such as Melissa McEwen, who take into account the many variety of foods that our ancestors could have consumed, and also acknowledge that humans have adapted since. “I refuse to take any dietary advice from people who clearly do not enjoy life,” writes McEwen on her blog.

McEwen makes an important point: What use is civilization, at least in it current form, if it doesn’t provide us with beauty and pleasure in the form of culture, art, music, literature, and, yes, food the way we’ve created it? To deny ourselves the chance to experience what’s available to us in the fullest way — especially if we’re in a privileged enough position to do so — is its own form of inadaptability. It may not have evolutionary consequences, but in the moment, depriving oneself of small pleasures can make that moment, not to mention passing along our genes, seem like it just isn’t worth it.

Many of the basic Paleo principles, as Zuk observes, are intuitive. She approves of “a simpler life with more exercise, fewer processed foods, and closer contact with our children” on common sense grounds. But we shouldn’t try to live that way just because our ancestors did. Evolution, Zuk points out, is continuous — not goal-oriented. Agriculture did not thwart a predetermined path towards enlightenment, and chances are, bread and rice aren’t stopping us from evolving, either. For better or for worse, there’s no undoing what’s been done — only coping as best we can with what we have before us.