The recent ubiquity of mermaids reflects the yearning to celebrate primal female energy in a culture that often denies it

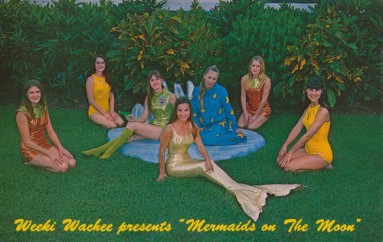

There have been a lot of mermaid sightings this summer, and not just at Coney Island but across pop culture. You might have seen the Little Mermaid roundtable in the Los Angeles Review of Books a few weeks back or the recent New York Times Magazine story by Virginia Sole-Smith about Weeki Wachee Springs, the legendary Florida mermaid attraction that was built in 1947 and still features live mermaid shows every day of the year. You might have watched Eric “the Mertailor” Ducharme, professional mermaid-tail maker (and merman), on TLC’s My Crazy Obsession. You may have read one of a number of stories about Linden Wolbert, a professional mermaid. Or you may have seen any number of new mermaid novels out there, including Michelle Tea’s Mermaid in Chelsea Creek and Sarah Porter’s just-published conclusion to her Lost Voices trilogy.

Not only can you read about mermaids right now, but you can become one. With the availability of mermaid tails online — you can buy inexpensive fabric ones, medium-priced latex ones, or elaborate, true-to-life silicone ones that will put you out a few thousand dollars — and the tutelage of professional mermaids like Hannah Fraser, who swims in the deep ocean with sharks and whales, suddenly it can be more than just a fantasy. The tails come equipped with monofins that make you swim faster and more fluidly, imbuing you with actual superhuman powers. For tips on breath-holding or tailmakers, you can go online and meet other mermaid enthusiasts — and other mermaids. You can go see mermaids at the Denver Aquarium, or at the Dive Bar in Sacramento, where a 7500-gallon mermaid tank hangs suspended over the bar, or at the historic Wreck Bar in Fort Lauderdale, where Medusirena and her aquaticats perform every Friday evening. You can even go to a full-on mermaid shop in Oceanside, California, where proprietor Mermaid Shelly will fit you with a custom tail and hook you up with a mer-made top and earrings to match.

Why mermaids? Why now? Are mermaids the new vampires, as a recent pieces at Huffington Post and ABC News claimed, or as a USA Today article argued in 2011, to cite just a few of numerous examples? Supposedly, even Twilight series author Stephanie Meyer herself is writing about mermaids.

Conflicted, frustrated sexualities are integral to both the vampire and the mermaid. But compared with vampires (or zombies too, for that matter), the mermaid makes for a much livelier figure: She’s not dead, for one, plus she has a bright, pretty tail and exists in full sunlight. And she’s female. (Mermen are so rare as to be culturally negligible.) She’s primal and wild, from the deep ocean — she is death and birth and the subconscious and the great mother. And typically she is represented as super hot — think of Daryl Hannah in Splash or pretty much any other mermaid you’ve ever seen — yet she might kill you if you get too close, as with the killer mermaids in Pirates of the Caribbean. Even Disney’s friendly flame-haired Ariel swims around shipwrecks and skeletons at the bottom of the sea.

But the appeal of the mermaid may depend primarily on her flexibility. Mermaids offer an image of female sexuality that is both potent and nonthreatening to men. As Stephin Merritt recently commented of mermaids, “I think straight men like the idea of women with all the knockers and none of the complicated parts.” Mermaids allow women to tap into something essential and powerful without becoming "unlikable" or unattractive. For women, mermaids offer the freedom of different interpretive options depending on her vicarious needs: Mermaids can be read as sexed or unsexed, vulnerable or terrifying, accessible or forever remote.

Historically, mermaids have been powerful, goddess-like, aggressive creatures, from the twin-tailed warrior Syrenka that watches over Warsaw to the West African water spirit Mami Wata (often represented as a mermaid) and Haitian La Sirene. Much of our current obsession, however, can likely be blamed on Hans Christian Andersen and his sad, very weirdly sexed, long-suffering Little Mermaid, who for love of a prince sacrifices her tongue and trades in her tail for legs, only to then be rejected by him and turn to foam. Thanks to Disney, this strange protagonist became a childhood icon for many mermaid-loving adults. Almost every mermaid lover I’ve met (and I've met many) mentions watching the Disney film as a formative moment in their lives.

Andersen wrote the original “The Little Mermaid” in a state of heartbreak, when his friend Edvard Collin, for whom he had a deep, not entirely brotherly affection (and whose name suspiciously resembles that of one brooding vampire), was off getting married, thereby inspiring Andersen to write the quintessential rejection story. This he did through the figure of the mermaid, who is so blatantly sexual and yet completely cut off from sexuality, literally without genitals. An apt figure for Andersen — who appears to have been celibate and yet fell in love with everyone in his path, male and female, and had a habit of recording his every masturbation session. And an apt figure for our own times, too, given that sexuality and gender have become more negotiable and thus more anxiety producing than they’ve perhaps ever been.

As I write this, I’m staying in Alaska with a friend who is currently transitioning. On the coffee table there’s a People magazine with a story about 10-year-old Nikki (formerly Niko), one of a growing number of transgender children on medication to inhibit the onset of puberty. This past May, Australia became first country in the world to recognize genderqueer as a legal designation, when a ruling that all citizens must be identified as either a man or a woman was overturned. A UK organization that offers support for “teenagers and children with gender identity issues” calls itself Mermaids; its logo features two mer-silhouettes with the look of two tadpoles, before and beyond gender.

While we can say that this gender flexibility is a good thing for human freedom, perhaps this new freedom creates confusion at the level of cultural symbols. Mermaids may provide a way to figure ambiguity for a world that needs such symbols more than ever.

I wrote a novel retelling Anderson’s mermaid story, with an emphasis on its suppressed weirdness and the mermaid’s morphing sexuality. To promote the book, I started a blog about mermaids in culture, but I didn’t anticipate how overwhelming it would become; mermaids are everywhere once you start looking, and the number of people out there who in some way base their identity on mermaids is staggering. I didn’t intend to become so mermaid focused, but when you start talking to women who slip on tails regularly, whether at Weeki Wachee — like Sole-Smith I attended the two-day mermaid camp there and fell in love its faded, forgotten glamour — or on a boat on the open ocean or beside some lake in North Carolina or Minnesota, it’s hard to resist. Former mermaid Barbara Wynns, who runs the camp at Weeki Wachee, sees helping women discover their inner mermaids as part of her life mission. Look past the kitsch at Weeki Wachee and you’ll see such a warm, passionate heart beating underneath. For these women, becoming a mermaid is a deeply meaningful, decidedly unironic act.

Over and over again the women I’ve met talk about transformation — and it’s infectious. Though I’d avoided the ocean all my life, four months after I went to Weeki Wachee I was getting scuba certified in Nicaragua. After her time at the camp, Sole-Smith spent this summer learning to swim.

In Weeki Wachee’s heyday, mermaiding represented an alternative to prescribed female roles. Back in the day “you could get married … or be a mermaid,” said Vicki Smith, who performed at Weeki when Elvis visited in 1961 and up until last year was a regularly performing “former” mermaid. In the 1960’s ABC owned Weeki; the shows were elaborate, choreographed, and ever-changing; celebrities were a regular presence and being a Weeki Wachee mermaid was the height of glamour. Weeki lost its cultural sway in the '70s when the Interstate, and Disneyworld, moved in. Less than two decades later, Disney’s Ariel would become the world’s most famous self-sacrificing mermaid.

But all these mermaids reappearing may signal a shift not only for women but for gender roles generally. Slipping on a tail, and the mythic identity that comes with it, is sacred, powerful. It evokes the freedom of being beyond gender, for a moment, while at the same time tapping into a primal female power so rarely expressed. The undercurrent of the mermaid’s power, suppressed by Disney and other cultural forces, is returning, in all its ferocious, primal energy of transformation.