“But so mighty a form must trample down many an innocent flower — crush to pieces many an object in its path.”

—Hegel, Lectures on the Philosophy of History

“Just think, the next time I shoot someone, I could be arrested for it.”

—Lieutenant Frank Drebin, The Naked Gun

Let us be plain: Cops are comic objects. And not just in film, not just in comedies. They are comic objects, period. That is, they are objects involved in the depiction of things as worse than they are, as Aristotle once defined the comic. Not a mistaken depiction, not a false judgment but that which both polices and reveals the “worse” that resides presently, however obscurely, within the categories, patterns, and relations that make up our social order.

But hold on, one might protest. Aren’t cops “subjects”? Even if you insist that cops are not part of that vaunted “99%,” surely they are part of that even larger percentage of “human subjects”? Because although the police is a general notion more than a local instance, it is nevertheless made up of “subjects” (individual cops) who, taken together, seem to make up a collective subject of sorts: an agency that acts with force upon the world and passes judgments on it, however disjointedly.

This, though, would miss the point. People who work as cops are subjects, sure — in an everyday, legal, economic, and philosophical sense. But the specificity of cop is that, while on the job, he is a negated subject. And this is far from a problem of the twists and shimmies of the dialectic: It deeply inflects how we interact daily with cops and, worse, how they disavow their hostile interactions with us.

A cop is a negated subject in two senses: as an expression of the law and as outside the sphere of reciprocal interaction with those to whom the law is applied. First, he

Even as cops naturalize criminalization and therefore themselves, they function by means of protecting propriety — or sensus decori, which Kant, in Metaphysics of Morals, defines as a “negative taste.” Cops remove the visible points of disorder that are “affronts to the moral sense, such as begging, uproar in the streets, offensive smells, and public prostitution (venus volgivaga).”

Yet contrary to the much vaunted “Protect and Serve” motto, the law does not actually protect individuals. U.S. courts have repeatedly ruled that it is not the legal duty or purpose of the police to protect citizens, starting with the 1855 Supreme Court ruling, South et al. v. State of Maryland, which argued that “no instance can be found where a civil action has been sustained against him [a cop] for his default or misbehavior as conservator of the peace by those who have suffered injury to their property or persons through the violence of mobs, riots, or insurrections.” The same holds true in the 20th century, in Warren v. District of Columbia (1975), and more recently in Castle Rock v. Gonzales (2005). In each case, the point is made that the police do not exist to protect individuals but only the propertied order. According to these precedents, they don’t even serve to protect individuals from those crimes — mobs, riots, insurrections — that threaten that order as a whole. Cops defend the peace, not the potentially peaceful.

Second, a cop is tautologically specified as “untouchable” by the same order of law that he enforces, the same one that declares individual subjects to be no concern of the police. Because the declared rules of engagement have different conditions for those involved (for example, for you and an officer on the same street), an exchange between nominal equals is utterly impossible. The possibility of a struggle, conversation, encounter, or discourse on terms that apply mutually to both parties is denied. The two cannot both be understood as subjects in the same register. They are incommensurable.

There is, I’d argue, a tremendous dread about this opaque nonrelation. It is lived and felt, from the sinking of the stomach as the flashers come on in your rearview mirror to the tightening of the stomach as you catch a glimpse of the pistol strapped to the standard-issue belt. (Not to mention the basic fact of airports and borders.) But it remains obscure, hard to name and elaborate. For that reason, it recurrently seeps through into a wide range of cultural products, including the “cop comedy,” one of the longest running genres in cinema across the 20th century.

***

In cop comedies, the dread bares itself in a number of ways. One of the most recurrent is to displace this anxiety into the sphere of queer subjectivity — most palpably, in a flood-level quantity of “gay jokes,” which are, of course, a not-so-secret thread through mainstream cinema in general. But the tenor of this nervous titter is different in the cop comedy and the noncomic cop film more broadly. In these films, the genuinely impossible object, the center of libidinal gravity and tidal pull, is the prospect of a queer cop. One instance, from the first Police Academy: two cops are kissing at an event commemorating new recruits. The commander thinks both cops are male and is aghast: You men, stop that! They turn. One is a woman. Oh well, says the commander. That’s more like it, Mahoney. Good man. Keep up the good work! Nervously, this queer slippage — one made all the worse through male and female cops wearing the same uniform, in an autoeroticism of the generic — will be shut down by a giggle or the revelation of an evidently female face. Nevertheless, there at the conclusion of the film, the palm sweating remains palpable, simultaneously horrified and excited by the thought that the police force could be eroded from within by a cop or two who enjoys differently.

Consider also the end of On the Beat, a 1962 British comedy. Two men, a cop and a hairdresser, are walking out of a church at the end of a wedding, together, beaming at each other’s faces. There has been reason to suspect that there was something “a bit queer” about them both. Then a zoom out and backward-tracking camera reveals that the wedding is not, after all, between the two men but doubled into a male cop marrying a passionate Italian woman and a male hairdresser marrying a dour female cop. We can practically hear the film’s exhalation of relief.

This dread runs equally throughout the “buddy comedy” subgenre, which has less to do with the patently obvious homosociality at work in them and far more to do with manifesting the internal incoherence of the cop object. It does this by splitting him into two “incompatible” but separate parts (the good cop and the bad cop, the neat cop and the messy cop, the black cop and the white cop, the human cop and the K-9 cop), thereby attempting to stabilize him through the context of the binary set.

This is also why so many cop comedies are about the process of becoming a cop — either becoming one legally for the first time, despite being short, fat, female, nerdy etc., or becoming the cop you have been all along. It’s easy to imagine the horror version: one wakes up, sweating, walks to the bathroom, switches on the light, and screams upon realizing that one is already wearing the uniform, that you can’t cut the cop out of you.

In other words, these cop comedies are stories of desubjectivation, though this is hidden in the guise of its opposite: people don’t “become the cop that they are” through submission to the law. No, they do so through fully enacting everything about them that seems opposed to being cop, such that they come to adopt their proper position as the principle outside the law which guarantees that law. No wonder, then, that so many of these stories focus on the the bumbling, hot-headed, kindhearted, too-drunk, womanizing, not-womanizing-enough, out-of-shape, too-short, wisecracking, or rebel “bad cop”: all these iterations work through the perspective that the perfect cop is the cop who seems totally out of joint with the institution of the police.

However, if we have been focused on what cops are, what about how they do? We can think about this in terms of two fundamental fantasies about the status and intention of the cop, both of which may “not be true” but which have been materially reinforced by an entire legal and punitive order and therefore became injunctively true: that is, they demand that they become the case, and they’ve got the force to back up the demand.

1. It is not permitted to defend oneself against the police: With them, there is only self-offense, and it shall not be allowed.

Cops are active objects (they arrest, detain, beat you) against which all action is forbidden (including fleeing from their action) and against which all action will be taken as purposeful (i.e. one cannot hit a cop as a human but only as a cop — only as an assault against the Law as such). If a pastry chef attempts to hit you, your hitting back or running away is indifferent to the specificity of pastry chef. If a cop attempts to hit you, anything you do will be understood only as a response to the specificity of cop. Whatever you do can and will be held against you. To put it in the form of a joke: A cop walks into a bar. The bar is arrested for assaulting an officer.

2. The police are not hostile: They merely react to, manage, and reflect the antagonism of the social order at large and of particular bad actions and people.

This notion is rooted in the long-held conception of the police as the guardians of the city, the keepers of the peace, the defenders of order. But to conceive of police as those who guard, keep, defend, means conceiving of polis, peace, and order as pre-existing and autonomous, such that the police are only a secondary order. It claims that a city is functional in itself; it just needs to be guarded, kept, and defended. However, “the city” is not identical to the particular city or populated zone, just as living citizens are not that abstract legal subject that is “protected” or “served.” Criminality therefore becomes the means for revealing the given incompatibility of a specific city and population with the polis in general defended by the police.

The police, therefore, are conceived as active yet not preemptive or structuring. They do not produce the antagonism they deal with. Rather they just reflect, manage, and try to contain the basic hostility at work in the inability of materials to correctly accord with social and conceptual structure. To be more concrete: According to the account of the police and their defenders, poor black communities are “violent” independent of the presence of cops. The fact of constant harassing, jailing, and killing of that community by the police, even if occasionally “excessive,” is merely a fact of “management” of the basic social anger that already is. Needless to say, even a cursory glance at urban history, particularly in the 20th century transformations of global north cities, should be enough to reveal this account as utter bullshit.

This perspective of “cops as reflection of existing violence” emerges on a few fronts, and, crucially, not just in cop comedy. There are, of course, the common routines of a cop who is shot at first, who has to smack a perp down because they would not go quietly, or who loses it for a moment, but only because the world at large is so hostile and chaotic and they killed his partner, but you know they messed with the wrong cop because he won’t rest until ...

But this also manifests itself in a very specific mode within cop comedies: Police violence is routed through the built environment such that the innate hostility of the world and its commodities are technically to blame (along with the targets of police violence). Guns and knives may be used, but primarily as sparks to set off the antagonistic powder keg called material existence. The consequence of this is the reinforcement of one of longest running taboos in cinema. Rather than blame police as such, responsibility for the violence is shifted to “unfortunate accidents” of psychosis (Maniac Cop), corruption (Bad Lieutenant), drugs (Bad Lieutenant), or vigilantism fascism (Magnum Force).

A few examples: Above all, hundreds of chase scenes, but let’s offer one in particular: that of James William Guercio’s underwatched 1973 Electra Glide in Blue, in which the fleeing subjects on motorcycles are steered or “steer themselves” into their own demise by cops on motorcycles. The point here is that the “correct cop” (Robert Blake) ensures that the correct procedure is to engage the landscape so that the criminals do themselves in, going so far as to shove his partner off his Harley when he threatens to break the code by opening fire on the perps. No, they have to be allowed to run into the car, to crash into the restaurant, to “happen to fall” into the path of a car that conveniently has no time to swerve. They are literally uncoerced; the police merely provide the occasion for this to be the self-ruining case.

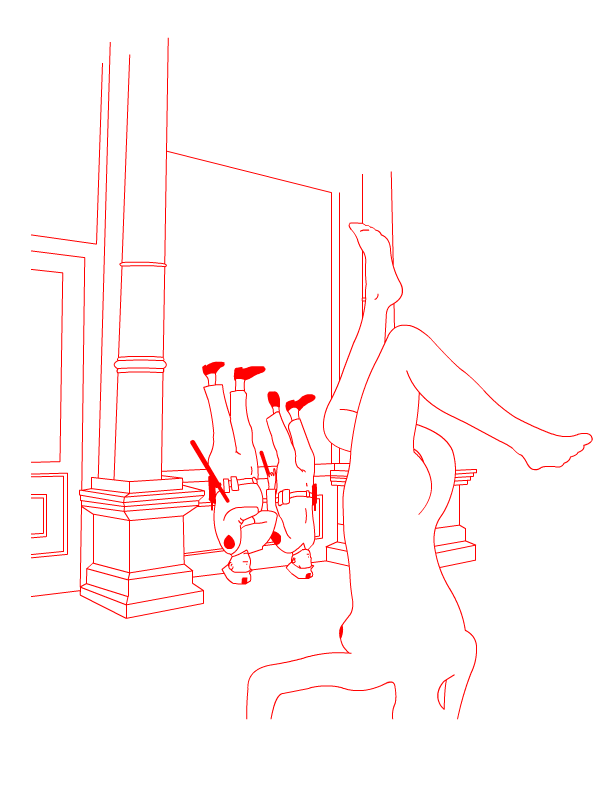

Electra Glide is, however, restrained in its treatment of “accidental” murder by landscape, limiting it to a concrete result of the bad combination of fast bikes and crowded, narrow roads. But in other cop comedies, that tendency will come fully unbound, depicting the world as already hostile, full of things ready to do you in, explosive gags of derailment just waiting for you to make the mistake of fleeing. In The Naked Gun (1988), a distracted criminal chased by Lieutenant Frank Drebin (Leslie Nielsen) will crash his car first into a gas truck, then into a missile carrier, and finally into a fireworks store. Standing in front of the enormous explosions, burning bodies, screams, and fleeing employees, Drebin says to the gathering crowd, “Move along, folks. Nothing to see here.”

This explains the tendency across the cop-comedy genre — and cop dramas and action flicks — to allow suspects to fall off a building edge (despite the cop’s best efforts to hold on), slip off a building edge while trying to punch the cop, land on their own knife because they were trying to stab a cop, crash the boat, the car, the helicopter, the plane, the motorcycle, be consumed in flames not lit by the cop but by the anxious combustibility of the modern metropolis. And when cops do draw weapons, when the prospect of wrongful force is raised, it is all the more circulated through the built world, so that a bullet may have started it but the line cannot be traced directly between the damage done and the trigger pulled.

Consider Hot Fuzz (2007), in which the cops shoot, with perfect aim, the tire of a nearby truck to let loose the barrels so as to knock the legs out from under an old man, all to avoid directly shooting him even though he is in the midst of reloading. This indirect firing is not for reasons of gore shyness: This is in a film in which a woman is stabbed with gardening shears, a chunk of cathedral impales a man, a couple is beheaded, and a man is burned to death in a gas fire, all with lingering lusty gazes at the sticky crimson aftermath. But when the police mete out violence, it is routed through the landscape, through chandeliers, barrels, shopping carts, and through the clumsiness of an antagonist who will find a miniature of a cathedral speared through his jaw, not because a cop put it there but because he tripped. It doesn’t kill him, of course. The villains all survive so that they can be sent to jail. Because, you know, cops don’t kill people. Bad people — subjects — and the armature of landscapes do.

***

Now we can finally say what police are: They are indirect hostile objects, inflections of the hostility they navigate and enforce. And this isn’t merely limited to instances in which a cop uses the landscape to achieve the arrest/murder he desires while keeping his hands clean. It also functions, most horrifyingly, in the way their casual, thoughtless actions — their passions, however seemingly distant from the law — serve to provoke situations (riots, looting) that retroactively declare the “necessity” of the police while disavowing any role they had in producing the disorder. Such is the case with almost all real-world instances of police gunning down suspects/young unarmed black men.

In Police Academy, it gets remarkable treatment, at the origin of the riot that will allow the police recruits to “become themselves” as police, by becoming recognized as a requisite force for the social good. One white cop is waiting in a car while his white partner is in a store. Around the car are men of various races, all of whom are coded as poor and tough. The second cop comes back to the car, climbs in, and gives the first cop an apple he bought him. The cop tosses it out the window, uninterested, and it hits a black man, who assumes it was thrown by a nearby black man eating an apple. They fight, the fight spills out, objects are knocked over, and in less than a minute, it has become a riot (“Hey everybody! It’s a riot!” someone yells excitedly into the billiards hall) — a riot which the cop who threw the apple, as well as the other police-to-be, must help “put down.”

At stake here, then, is the basic logic of cunning. And here, a turn to the horse’s mouth — i.e. Hegel — is necessary.

It is not the general idea that is implicated in opposition and combat, and that is exposed to danger. It remains in the background, untouched and uninjured. This may be called the cunning of reason, — that it sets the passions to work for itself, while that which develops its existence through such impulsion pays the penalty and suffers loss. For it is phenomenal being that is so treated, and of this, part is of no value, part is positive and real ... The Idea pays the penalty of determinate existence and of corruptibility, not from itself, but from the passions of individuals.

— Lectures on the Philosophy of History, § 36

One could certainly think about this in the way that the “individual passions” of police officers — let’s say, a certain hastiness of the trigger finger — makes the “particular” (the lives of those deemed criminal) pay the penalty for the perpetuation of a general idea, such as the “law and order” of civil society. However, we can think of this in terms of the larger structures of capitalist development as well. Because the general idea — say, the historic development of capital as a globally and locally structuring relation — generates a set of contradictions that it can neither handle nor accept. It gives shape to and calls into being (“that which develops its existence through such impulsion”) particulars: entire cities, categories of objects, mines, factories, populations, social structures and identities, and uses of time.

Moreover, think of the composition of the objects (laborers included) capital generates, employs, and destroys: “part is of no value, part is positive and real.” Of course, with capital, it is — surprise! — an inversion: The valued part is not positive or real but the nonpart that exists only as the possibility of exchange (i.e. the negation of particular quality, or potential use, in the moment of commensurability); while the part that is positive and real (a use value, a life to be snuffed out, an activity across time) is unvalued and pays the penalty. If it is some grain in a period where the general laws of capital declare the global price of grain to be too low, it will be left to rot by the “hand of the market” or by state intervention. If it is an activity — say, the harvesting of grain — that cannot be profitable in a certain period, it will cease to be done so as to preserve the health of the general circulation of wealth, the declining health of populations be damned. And if it is a body…

But the full breakdown of these manifold things (the collapse of access to jobs, the starvation of populations) doesn’t call into question the basic abstractions that generated and inflected that breakdown. No, that general relation continues on, “untouched and uninjured,” finding new sites and materials. And it does so until the passage of the general through the particular — i.e. the way that capital must circle through labor — is impeded by that particular itself, when the particular stops acting as the conduit and becomes a point of stoppage.

So it is that we might put another term alongside that of cunning: sabotage. Because the two are inseparable, two inflections of the same punishment of the particular. But in opposite ways. In cunning, the general is strengthened by the attack of the particular on itself: the destruction of potential exchange (letting food spoil on the docks, however needed it may be by people) means that new production, and therefore new circulation and exchange, must be impelled. In sabotage, the general is wounded by that attack: commodities are refused entrance into circulation — by people who impede production, who “go slow,” who taint the product, who block ports, trains, and roads — in order to attack the flows that make up the accumulation and persistence of the general relation.

Between cunning and sabotage, in that thinnest of spaces, stand the police, trying desperately and ridiculously to prevent them collapsing together. That fractional space is also the real site of the comic, siding with neither cunning nor sabotage, but slipping between the two, the gag shoving objects — including cops — from side to side.

We ask what comedy can’t vocalize: What would it mean for the general to pay its own penalty? For the relation of capital to bear its own costs? It would mean a collapse of law in all forms. A material critique of separation, between cunning and sabotage, and the end of displacement or dislocation.

Comedy doesn’t speak this, but it says something important all the same. It insists that we live in a world of matter and acts and gags, that the shaming of the general doesn’t occur on its own terms but only and ever through the particular, through the reconning sabotage of its materials brought to bear on themselves. That is, through the occasion we produce for the police to barricade themselves, to be halted by a wall of their own making.

In The Blues Brothers, this gets enacted literally, as the attempt of the police to catch fleeing suspects leads to them crashing into one another, until the cars pile up and they are physically barricaded behind a wall of their own making and material, yelling Son of a bitch! They stand on top of the auto blockade, firing their guns pointlessly toward where that obscure object of crime has sped.

To be sure, in a world and a century of cinema that can only ever joke, and only ever briefly, about the hostility of cops, this is cold comfort. But like that decision to slam the foot on the gas pedal when the flashers appear in the rear-view mirror, it is a point of departure.