To turn the US-Mexico border into “The Border,” America had to erase its Caribbean history

In December 1994, the government of Panama told the United States that it would no longer permit the U.S. to use Howard Air Force base as a “safe haven” camp for Cuban refugees. The announcement came at the end of a series of what the Defense Department called “disturbances” during which two Cubans died, 30 suffered injuries, and 221 U.S. soldiers were wounded. More than 30 people held at the camp would try to commit suicide. The U.S. would end the Panama operation by March 1995. This Caribbean chapter of U.S. border history is largely forgotten. This forgetting is a strategic erasure, a shadow produced with the hyper-visible U.S.-Mexico border spectacle.

Camp One on Howard Air Force Base and Camp Bulkeley at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base were at the center of an archipelago of military and civilian spaces established or planned as “safe havens” across the Caribbean in 1994. The Clinton administration secured agreements from other nations in the region—including Panama, Dominica, Suriname, Grenada, St. Lucia, the Turks and Caicos, and the Bahamas—to provide sanctuary (or “processing” space en route to sanctuary) to people fleeing political repression in Haiti and Cuba.

Even as the “safe haven” crisis was unfolding in the Caribbean, the Clinton administration rolled out its new national strategy to “control the borders of the United States between the ports of entry, restoring the Nation’s confidence in the integrity of the border.” The Border Patrol strategy—called “prevention through deterrence”—was developed in consultation with the Defense Department’s Center for Low Intensity Conflict, and aimed to prevent unauthorized entry. The strategy entailed the deployment of more Border Patrol agents, increased fortification and surveillance of the boundary, and harsher sanctions. The plan centered on the U.S. Southwest, prioritizing securing the boundary between El Paso and Juárez and San Diego and Tijuana, before moving on to the Tucson and south Texas sectors.

These borders are more than fortifications along international boundaries; border operations are performative. In Border Games, Peter Andreas argues that strategic images and symbols of the border “are part of a public performance for which the border functions as a political stage.” Moreover, Alison Mountz writes in Seeking Asylum, “Visuality is an affective register through which sovereignty is secured.” The border spectacle produces not only a sense of beleaguered nationhood on the part of some U.S. citizens, but it also positions the state as a protector of the nation and, contradictorily, as the protector of migrants who themselves are endangered by the state’s militarized policing and profoundly elitist migration laws.

To call the border a spectacle is not to say that it is unreal or that its effects are not deadly. Spectacles, following Guy Debord, are not false distortions of reality. Rather, they are “a worldview translated into an objective force” that shapes what is seen and unseen. Cultural theorist Shiloh Krupar, in Hot Spotter’s Report, usefully conceptualizes spectacle as “a tactical ontology—meaning a truth-telling, world-making strategy” that creates powerful symbolic divisions between people and places that are actually deeply intertwined.

The Border Patrol acknowledged as much in its strategic plan when it concluded that “the absolute sealing of the border is unrealistic.” Indeed, the plan was launched in 1994, the same year as the North American Free Trade Act (NAFTA) was implemented to further integrate economies of the region. Nonetheless, the border spectacle had the immediate and enduring effect of funneling attention and anxiety over border “control” away from the Caribbean and isolating it along the U.S.-Mexico boundary. This spectacle builds on long colonial histories in both regions, but Attorney General Janet Reno’s claim that the Border Patrol’s 1994 strategic plan was “necessary to establish a border for the first time” obscures this past, the Cold War development of deterrence doctrine in the Caribbean, and deterrence strategy’s harmful effects.

Following the 1980 Mariel boatlift—during which more than 125,000 Cubans and 25,000 Haitians arrived in south Florida over a six-month period—the Reagan administration established a two-pronged strategy of interdiction at sea and mandatory detention intended to deter migration and prevent “another Mariel.” The U.S. did not issue a formal refugee policy until 1980, but even after implementation, the Immigration and Naturalization Service and State Department continued to make refugee determinations on the basis of Cold War geopolitics. This phenomenon was most famously depicted in a scene in the 1983 movie Scarface, when the wily Mariel boatliftee tries to appeal to what he assumes are his immigration interviewer’s anti-communist sentiments: “I am Tony Montana, a political prisoner from Cuba, and I want my fucking human rights, now! Just like the President Jimmy Carter says.” Asylum seekers from enemy nations like Cuba were treated by default (for a time) as freedom fighters, while those seeking refuge from ally nations were categorized as economic migrants or illegal entrants and denied entry.

Under the Duvalier regimes (1957–86), Haiti was a Cold War ally of the U.S., and the U.S. developed the dual strategy of interdiction and detention to prevent migration from there. In the mid-1970s, the Department of Justice (then in charge of the INS) ran what it called the “Haitian Program,” which a U.S. District Court for South Florida ruling called a “transparently discriminatory program designed to deport Haitian nationals and no one else.” The routine exclusion of Haitian asylum seekers in the 1980s and 1990s was a continuation of these Carter-era practices.

When thousands of people left Haiti after the first ousting of populist President Jean Bertrand Aristide in 1991, the U.S. continued to interdict boats and conduct “credible fear” interviews on board Coast Guard cutters. With so many people departing Haiti, George H.W. Bush issued a new policy that year stating that Haitians who had been “screened in” would be transferred not to the U.S. mainland but to the base at Guantánamo. As the base’s captive population grew to more than 12,500 people, the first Bush administration issued yet another policy ordering interdiction and direct return. While the United Nations Refugee Convention prohibits signatory nations from returning people to places where they fear for their lives and political freedoms, the U.S. offered a legal interpretation that the principle of non-refoulement did not apply outside of U.S. territory.

Advocates challenged the legality of asylum hearings on Guantánamo and returns to Haiti. Approximately one-third of the Haitian people who had sought asylum were able to gain entry, and by May 1992 some 300 people remained on the base. They had all been classified as refugees, but also were infected with HIV, and the U.S. refused to admit them. Following still more legal efforts, a judge ruled that the Haitians’ First Amendment and due process rights had been violated and that they should be immediately admitted to the U.S. The Clinton administration eventually complied with the ruling, closing the camp in June 1993.

But the camp did not stay closed for long. When the deal negotiated on New York’s Governor’s Island to reinstate Aristide fell through, political reprisals escalated, and tens of thousands of Haitians once again attempted to find safety in the U.S. Despite having just brokered Aristide’s return, the Clinton administration maintained the previous practices of onboard screening and direct return. Facing substantial criticism, Clinton implemented a more liberal screening process, and ultimately issued a “safe haven” policy wherein people who passed credible fear interviews would not be returned to Haiti, though they would also not necessarily be granted entrance to the continental United States either. By July of 1994, Guantánamo was once again a refugee camp, where 16,000 Haitians found themselves effectively shut out from gaining asylum in the U.S.

Meanwhile, a political crisis in Cuba erupted and more than 30,000 Cubans departed by boat. Before they could arrive in Florida, they were also interdicted. Approximately 23,000 Cubans were detained at Guantánamo and another 9,000 were airlifted to Howard Air Force Base in Panama. Attorney Harold Koh, who was one of the leading critics of the operations, concluded: “In effect, we have built offshore cities of more than 20,000 people without constructive outlets, with little to do besides getting frustrated.”

A decade of legal battles over these practices left many human rights advocates, including Koh—who joined the Obama administration as a State Department legal adviser in 2009 and made headlines with his defense of the President’s targeted killing program—in the unenviable position of supporting “safe haven” campus as the least-bad option. The establishment of internationally monitored “safe havens” located within regions of conflicts—rather than resettlement in the U.S. or Europe—was part of a broader trend following the end of the Cold War. While these nations portrayed “safe haven” as humanitarian measures, legal scholar Joan Fitzpatrick argued that it “instead constitutes one more device to constrict access to asylum.”

Post–Cold War geopolitics certainly contributed to the profound shifts in refugee “management” worldwide, but geopolitics is still local. In Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond, border scholar Joseph Nevins shows how local restrictionist politics drove national policy. In California, the 1994 election featured a hotly contested anti-immigrant ballot initiative (Proposition 187) and a gubernatorial race between Republican governor Pete Wilson—a former mayor of San Diego who had long taken a hard-line stance against “illegal immigration”—and Democratic candidate Kathleen Brown, who called for a high-profile border operation in San Diego like the one that had just been tried in El Paso (Operation Blockade, later Hold the Line). The implementation of Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego following the Border Patrol’s announcement of its strategic plan, Nevins concludes, was “a political sideshow designed for public consumption to demonstrate the Clinton administration’s seriousness about cracking down on unauthorized immigration.”

President Clinton knew the stakes of these election-year immigration crises were high; he lost his 1980 gubernatorial reelection in Arkansas at least partly because of fallout over the confinement of “Mariel Cubans” at Fort Chaffee. Indeed, the high profile of the joint civilian-military operations in the Caribbean during the summer of 1994 were also positioned for the benefit of Florida Democratic gubernatorial candidate Lawton Chiles, who was seeking re-election against Republican Jeb Bush. Governor Chiles, one aide told the New York Times, “made every effort at preventing Mariel II.”

The remarks that Clinton delivered to the “Cuban-American Community” after the pivotal 1994 election and shortly after the closure of the camps in Panama illustrate the spectacular staging of the border to a specific audience:

In the summer of 1994, thousands took to treacherous waters in un-seaworthy rafts, seeking to reach our shores; an undetermined number actually lost their lives. In response, I ordered Cubans rescued at sea to be taken to safe haven at our naval base at Guantánamo and, for a time, in Panama. Senior United States military officials warned me that unrest and violence this summer were likely, threatening both those in the camps and our own dedicated soldiers.

But to admit those remaining in Guantánamo without doing something to deter new rafters risked unleashing a new, massive exodus of Cubans, many of whom would perish seeking to reach the United States.

Clinton’s attention to the peril facing Cuban migrants deploys terms of safety and order in an effort to rationalize the administration’s sharp departure from the welcome that Cuban refugees had long received as defectors from a Soviet satellite.

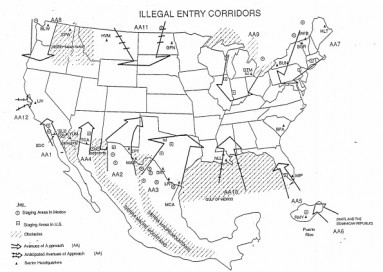

Yet these operations are noticeably absent from the Border Patrol’s 1994 strategic plan, despite the fact that monthly costs for the Safe Haven operation had reached $30 million. As the map included in the plan illustrates, South Florida and Puerto Rico are listed as fifth and sixth priority regions, just ahead of the northern border states of Washington and New York.

The spectacular funneling of “the Border” to the U.S.-Mexico borderlands worked to contain operations in the Caribbean and separate them from the “national” deterrent project. This separation could be achieved not only by dividing political refugees from economic migrants but also by tactically erasing the deterrent strategies of interdiction, mandatory detention, and “safe haven” developed to control migration from the Caribbean.

The spectacular containment of Haitian migrants in the Coast Guard’s scopic target, as seen in the December 2013 image on page 14, reifies a vision of state protection while effectively erasing the violence of militarized border and asylum policies. Meanwhile, as Todd Miller writes in Border Patrol Nation, the U.S. response to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, which left more than 1.2 million people without homes, included the deployment of additional Coast Guard cutters to prevent boat departures. Although the Caribbean border has been officially deprioritized, deterrence policies implemented there helped to produce a militarized border and detention regime nationwide. While these practices create harsher conditions for those seeking safety (or a livelihood), border spectacles shift the danger of “the border” to the nation, and away from migrants who endure treacherous crossings and prolonged detention. Border spectacles rely on this separation to work, lifting the burden of migrant deaths from the state policies that knowingly cause them, and putting it on migrants themselves.

Deterrence as a policy was never solely directed against external “threats,” but also aimed to prevent struggles of migrants in U.S. territory to remain. Because expulsion is difficult—legally and politically—the U.S. turned to deterrent practices that would contain through mainland detention and deny entry by shifting the border offshore through interdiction at sea and militarized “safe haven.” Challenging current pushes for further border militarization will mean countering the spectacular erasure of ongoing Caribbean histories of deterrence by reconnecting it to the border spectacle deployed along the U.S.-Mexico boundary. These intertwined histories of presence and expulsion reveal shared struggles against deadly state borders that we can continue to build.