Spike Lee's films recall the "life-building" of the art of the early Soviet Union.

I’m on a mission to bring our shit, undiluted, uncut to the screen.

—Spike Lee, Valentine’s Day, 1988

Tracee and I went to see School Daze during that week of celebrating Spike Lee all over (black) Brooklyn. The small theater at BAM was about half-filled, with mostly black couples and groups our age (early-tomid-30s) and older. The few outliers appeared to be single white men, with whole rows to themselves. As the delirious ode to American musicals tumbled out across the screen, in the raucous cadence of a black middle-class college at the end of the last century, the audience danced and sang along in their seats, alternatively laughing and sucking their teeth in recognition. Lee’s film glows with the spectrum of colors and registers of sound that make black life so astonishingly luminescent within a society of locked doors and drawn curtains. Like Nella Larsen’s painterly depictions of Harlem Renaissance nights, School Daze fills the entire screen with all the gestures and grace of a sweaty black club. At times, especially during the genius pajama-party scene, when that paleo-twerk classic of D.C. go-go music, “Da Butt,” sails over a sea of tightly packed asses rolling in waves, and we, the audience, roared and writhed along in our seats, I felt an overwhelming love for Spike Lee and everyone involved in bringing this film into my life. In School Daze, the plot is not the thing, just as in jazz, the melody is never the thing. Instead, it is the cascade of ghosts of black lives we have lived and witnessed, which first thrills us in the theater and then leads us to the subway in silent mourning.

What becomes clear as we leave the movie theater is how rarely we experience representations of black American life that resonate with our realities. The old lament: When we will see our “true” selves on the screen? But it is much more difficult to articulate what exactly it is that will make us whole, that will assuage years of malicious “Hollywood” treatments. In this essay I do not purport to give a step-by-step explanation of what it would take to deliver on-screen reparations for crimes against veracity. Nor will there be further talk of representing “true” selves. More interesting to me are the (rare) depictions of everyday black life, which affirm our existence in complex worlds, floating parallel to the mainstream. Are these simple acts of rendering, or is something more required of the “painter of modern [black] life”?

The last scene of School Daze has Dap, the campus militant, running across the main lawn in the wee hours of the morning after the night’s climactic party to ring the school bell, yelling, “Wake up!” over and over. A sleepy, solemn crowd gathers, and Dap silently locks eyes in a conciliatory gaze with his arch rival, a decidedly apolitical fraternity brother. “Please wake up,” Dap pleads with us, breaking the fourth wall. The frame freezes, the color drains to black and white, and an alarm bell rings. Who exactly is Dap talking to, anyway? Looking at the animated faces of my fellow moviegoers, it is clear he’s been talking to us—us black folks. And this is the first requirement for anyone who would take on the complexity of our existence—we must be (at least a part of) the art’s intended audience. A lot of American art and art criticism, no matter the racial or ethnic makeup of the creative team, is made for some imagined white America. That elusive yet endlessly sought-after demographic bears the dubious distinction of being the “target audience” for almost everything on TV, in the cinema, on the stage, and certainly in the art galleries and museums. Any depiction or discussion of black people that has as its intended audience primarily white people will never be able to see us, to fully acknowledge the registers in which we exist. All that will be on offer for us instead is to be mocked and disremembered, or maybe just dismembered.

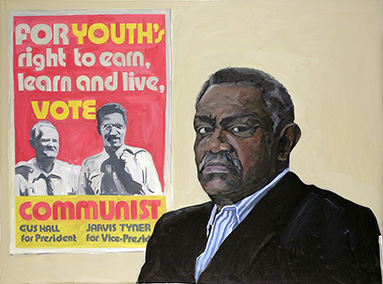

Recently, Russian artist Yevgeniy Fiks got the idea to collect all the images he could find of Africans and African Americans created by Soviet artists between the 1920s and the 1980s. As a young artist in Moscow, Fiks was trained in social-realist painting and has turned that skill to documenting the communist world that, despite all odds, continues to exist in the United States. Upon visiting the New York headquarters of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) on a mission to paint portraits of the group’s contemporary members, Fiks was surprised to find that artists Langston Hughes, Ralph Ellison, Paul Robeson, and Richard Wright, among others, had all been card-carrying members. He began to investigate the relationship between black political struggles and social movements, the CPUSA and the Soviet Union. His investigations uncovered long histories of mutual political support between black America and the Soviet Union, from its early years and into its decline. His original project, of painting members of the CPUSA in an anachronistic Soviet social realist style, gave way to a search for representations of black Americans made by other Soviet painters. The archive of more than 200 images is named for Wayland Rudd, a Philadelphia-born actor who traveled from New York to Moscow in 1932 as part of a delegation of black artists and never returned to the States. Taken as a whole, the Wayland Rudd Collection represents the possibility of an alternative experience of black Americaness, constructed in a country that no longer exists.

Of particular interest in the collection are the sketches and paintings of Aleksandr Deineka, a Kursk-born painter who, in the 1920s and ’30s, contributed to the invention of the social realism that became the stylistic stamp of Soviet art and propaganda. In late 1934, Deineka traveled from Moscow to New York on a three-month art residency sponsored by the Union of Soviet Artists. He spent time in Harlem, making sketches of everyday (and night) life. His pictures of people just going about their business resemble, in their attention to normality, strains of modernism arising in the Harlem Renaissance. These new forms of writing, dance, music, and image-making sought, in the rhythms of regular folks’ speech and gestures, the poetic humanity denied black people in mainstream “primitivist” representations and appropriations of blackness. Deineka’s figures—women attending a lecture, a thoughtful young man with downcast eyes, an elegant singer and his accompanist at the piano, a pair of clubbers with their skirts hiked up—could be drawn directly from Larsen’s stories of middle-class Harlem moderns, who went from ladies’ luncheons to jumping speakeasies in a single day.

Deineka’s depictions of particular black lives bear marks of what early Soviet art theorists called “zhizhnestronie,” or life-building. Life-building was a critical area of design for the young nation, by which the novy byt, the new way of living, would be created, and artists were asked to lead the effort. According to Art in Production, a collection of essays published in Moscow in 1921, the purpose of art is “the introduction of artistic elements into the life of production,” and to bring about both the “transformation of the form of the production process and the form of everyday life.” Art would no longer be, as art writer Nikolai Punin put it at the time, “a holy temple where the lazy only contemplate.” Instead, the new art would be a joint project of social activists and “art-makers” committed to creating “a future consciousness.” Playwright Sergei Tretyakov was even more specific: the new “art worker” would be a “psycho-engineer, a psychological constructor,” working to “reorganize the human psyche with the goal of achieving the commune.” Transforming the means by which art was produced was key to developing art forms in solidarity with the nascent proletariat society. Art could no longer be a method for “raising questions” and “understanding life,” but would have to create entirely new lives. Art would need to work in the streets, not merely in the studios, galleries, and museums. It would eventually have to be no different from any other kind of work—“a temporary activity, which in future will be dissolved into life.” Art historian Christina Kiaer describes Deineka’s way of making pictures as a kind of “supercharged mimesis,” which “infects” the viewer, such that he or she can “imagine other affective possibilities under socialism.” It is possible that Deineka’s pictures express co-feeling for Harlem and its residents, many of whom were part of the decades-long Great Migration of black people fleeing terrible conditions in the South. Maybe he experienced in the neighborhood the energy of a proletariat struggling to recognize itself through new art forms, to rebuild life in its own image.

Somewhere between the premiere of School Daze, and the start of shooting on Do the Right Thing, Spike Lee also got a close-up look at what happens when black folks try to make pictures of themselves for themselves. On January 14, 1988, upon learning of Columbia Pictures’ refusal to provide both television advertising and print promotion in major black publications like Ebony, Jet, and Essence, Lee writes in his journal:

All they see is niggers: nigger director and nigger audience, second-rate, second-class shit; therefore the project is not worth their time and money. I’m gonna have to carry School Daze myself on my back. And when it takes off, without any effort on their part, Columbia will claim they knew it all along.

What gives Lee confidence in his filmic vision is the conviction that “black audiences are starving for films by and about us.” With the artists of the young Soviet Union, who sought to construct an art of and for the proletariat, Lee shares a commitment to building worlds—both on screen and off—that are safe for black youth. This is why the BAM theater felt so welcoming: The images were for us, challenging works of art for which we were the primary audience. According to theorist Nikolai Chuzhak, art as life building was fundamentally about “welcoming the growth of a form that could be a fellow traveler to the proletariat, ‘nudging’ and helping it to reorganize itself.” Our survival as a people depends upon the arrival of “fellow travelers,” sometimes strangers, sometimes familiars bearing new forms, who will contribute to our remembrance—our “re-memberment”—who will help us with our project of perpetual reconstruction.

With School Daze and She’s Gotta Have It, we’ve started something. Young black people are coming together, as one, to make our own films. It’s never been done before on this scale. What we’re doing is revolutionary and courageous. No other black people in the industry are doing what we’re doing. I’m not bragging, I’m just sorry it isn’t being done by more folks.

—Spike Lee