One never knows what to expect from the up-and-coming French philosopher Quentin Meillassoux. I certainly didn’t expect his second book-length work to be a “decipherment” of Stéphane Mallarmé’s enigmatic final poem, Un Coup de Dés jamais n’abolira le Hasard (A Throw of Dice Will Never Abolish Chance). Still less did I expect it to be so absorbing and thrilling. The Number and the Siren is an erudite work of literary criticism, tackling one of the most difficult of modern poets, and yet I feel compelled to begin this review with a comparatively base warning: Contains spoilers!

Meillassoux’s flair for the dramatic twist is one of those rare coincidences when a philosopher’s style and thought match up perfectly. His entire work is centered on the conviction that the universe is a much stranger place than we ever could have guessed, leaving room for even the most outlandish hopes. In his first major published work, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, he argues for a view of the world centered on contingency rather than necessity — that is to say, for a universe ruled by chance rather than by any foundational laws. If our world appears to be regulated by immutable natural laws, that’s just a coincidence, a state of affairs that could easily change. Similarly, if it seems indisputable that there’s currently no God, that’s no reason to assume a God couldn’t pop into existence at some future date.

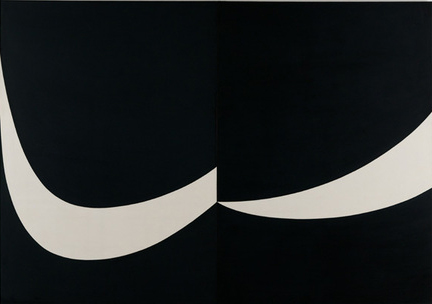

It seems natural, then, that Meillassoux would be drawn to Mallarmé’s meditation on contingency and chance, which is included in the original and in a fresh translation in an appendix to The Number and the Siren. As Meillassoux summarizes it, Un Coup de Dés centers on the aftermath of a shipwreck, which leaves a mysterious “Master” with one seemingly meaningless final choice: whether to throw a pair of dice. It is never revealed whether he actually does so, and he is pulled into a whirlpool. Along the way, we are treated to an enigmatic vision of a siren who destroys the rock that presumably led to the shipwreck, and various reflections on “the unique Number that cannot be // another.” The poem closes with the suggestion that a new stellar constellation may, perhaps, have been set in motion by the Master’s dice-throw. All of this is presented in a unique layout, with lines stretching across two facing pages, varied typography, and virtually no punctuation.

In Meillassoux’s reading, Mallarmé is reflecting on the task of the poet in the wake of the “shipwreck” of traditional poetic form occasioned by the rise of free verse. Where he breaks with most contemporary interpreters, however, is in seeing Un Coup de Dés as part of Mallarmé’s attempt to create an artistic form that could found a modern ritual with all the power and meaning of the Roman Catholic Mass. This project centered on the composition of a liturgical poem called “the Book” that would be part of a numerologically structured ceremony of public reading.

Many critics view this ambition of Mallarmé’s as crazy and embarrassing, something that he surely got out of his system by the time he wrote his final great work. Meillassoux, however, not only claims that Un Coup de Dés is a continuation of the project of the Book, but that—thanks to Meillassoux’s own investigation, which effectively unlocks the meaning of the poem—Mallarmé has in fact actually succeeded in an achievement that could found a new poetic religion that would be secular modernity’s answer to Christianity.

Stéphane Mallarmé is, in short, a modern-day Jesus, and Meillassoux is his St. Paul.

* * *

Now when I put it like that, it sounds crazy. When one reads it as part of Meillassoux’s tightly constructed argument, it also sounds crazy, but in a different way: It is undeniable even as it seems impossible. It works like a surprising “big reveal” in a detective story, the kind that prompts a joyful cry of “No way!” There are other similar moments throughout The Number and the Siren, which has the kind of literary quality I have come to associate with French philosophy at its best — above all, the work of Derrida, which abounds in such “big reveals.” The experience of reading Meillassoux’s essay is akin to the experience of reading “Plato’s Pharmacy” and marveling at how Derrida manages to make the little word pharmakon appear to be simultaneously the foundation and the undoing of Plato’s entire philosophical project.

Yet one might justly ask: is there anything more to Meillassoux’s investigation than the pleasure of an interpretative tour de force? To answer that question, we need to look at the other major slice of Meillassoux’s writings to which we have access: the selections from his unpublished dissertation, "The Divine Inexistence," published in Graham Harman’s study of Meillassoux. These selections, which build off of the argument for contingency found in After Finitude, represent an ambitious attempt to account for all of reality within his philosophical scheme — from matter and organic life to humanity and what might come to supersede it.

Each new level of complexity, for Meillassoux, stems from an unpredictable event that surpasses the horizon of what came before while still formally respecting its laws. Meillassoux argues, for instance, that no one could have predicted that organic life would emerge from inorganic matter. The principle of life is not simply an extension of the principles governing inert matter, though life still rests on a foundation of matter. Similarly, human consciousness is qualitatively different from mere organic life, even though it relies on an organic foundation. One cannot account for the decisive events that brought about life and consciousness in terms of what came before—indeed, a (necessarily hypothetical) observer would have regarded them as impossible.

Nevertheless, Meillassoux believes that we can trace out the shape of the next event that will transcend humanity as we know it. Humanity’s great failing for Meillassoux is the cold, hard reality of death, which keeps human intellect from fulfilling its vocation to grasp the infinite. One might hope for something like the immortality of the soul in order to overcome this obstacle, but this would not fit the pattern that Meillassoux had established for the previous events. All of those transformative events rested on the foundation of the stage before it, while the immortality of the soul would simply leave embodied human existence (and hence the organic and material levels that provide its foundation) behind. The next stage of humanity must be material, must be organic and bodily — but it will be immortal. What’s more, this event will not apply solely to those who happen to be living when it happens. It must overcome the death of all human beings, allowing them to fulfill their vocation.

Obviously all of this sounds suspiciously like the Christian doctrine of the resurrection of the dead.

Given that his breakthrough philosophical work seemed to most readers to represent a particularly radical form of atheism, this embrace of the resurrection of the dead is, to say the least, off-putting. Admirers of Meillassoux have generally reacted negatively to this particular aspect of his work, viewing it as crazy and embarrassing. Some have even hypothesized that Harman has somehow chosen the excerpts maliciously in order to discredit him. This scenario that is basically impossible, given Harman’s great admiration for Meillassoux and Meillassoux’s own collaboration on Harman’s book, but the fact that it would occur to them shows the sense of betrayal and even trauma this part of Meillassoux’s thought has prompted.

As someone whose academic training is in theology, I was naturally more receptive. This is not because I am a huge fan of actual-existing Christianity, but because my greater familiarity with the diversity and debate within Christianity showed me that Meillassoux was far from embracing anything like the conservative or orthodox position many of his admirers are likely reacting against. First and most obviously, Meillassoux remains an atheist. To the extent that he posits some form of divinity in the mediator figure who will bring about the resurrection, it’s a divinity that he will set aside after achieving the resurrection — meaning that Meillassoux is more akin to the radical “death of God” theology associated with Thomas Altizer and recently revived by Slavoj Žižek.

In short, insofar as Meillassoux is “embracing Christianity,” it’s an extremely weird version of Christianity that almost anyone who currently calls themself a Christian would surely reject. More than that, it follows in the pattern of previous left-wing attempts (by both atheists and believers) to redeploy Christianity in the service of radical politics — a connection that is all the stronger insofar as Meillassoux uses the hope of the resurrection as the starting point for an ethics based in radical equality.

* * *

Yet in light of The Number and the Siren, I don’t think it’s really accurate to say that Meillassoux is embracing or appropriating Christianity. What he’s really trying to do is much bolder and, one might say, more insane: He wants to do Christianity one better. He wants to create something more powerful than Christianity, something that would radicalize Christianity’s wildest hopes — and that would deliver, insofar as it’s based on the radical contingency of the universe rather than on the illusion of a transcendent God.

In The Number and the Siren, then, he is not exactly claiming that Mallarmé is Jesus, but that he’s better than Jesus. For Meillassoux, Mallarmé has accomplished something real, showing us that it’s possible for a human being to attain to the infinite. This is undoubtedly a hard teaching—who can accept it?—but it’s just as undoubtedly an audacious teaching, one that is worthy of our attention as it continues to unfold.