Small Arms, Long Reach: America's Rifle Abroad

ON January 16th 2016, two California National Guardsmen pleaded guilty in a Federal court to a variety of weapons trafficking charges. They had previously worked in an Army National Guard armory not far from San Diego, and, being entrepreneurial sorts, had gone about gathering a small cache of guns to sell themselves. Some were military-issued, others were purchased in Texas (both over-the-counter, with serial numbers, and “hot,” with serial numbers defaced). The Guardsmen thought the guns were destined for south of the border; in fact, their client was an undercover ATF agent, and his purchases from the Guardsmen – three AR-15-style rifles, an AK-47, numerous high-capacity magazines, more – ultimately wound up as evidence at their trial, which was well-reported. Coverage from multiple sources all underlined one particular detail: for one of their meetings with that ATF agent, the two soldiers had arrived in full military uniform.

But who cares what they were wearing? Americans garbed in the trappings of authority and respectability have been involved in illicit arms deals with cartels before. Just five years earlier, eleven people in a single New Mexico town were all found guilty of smuggling hundreds of AK-47s into the Mexican state of Chihuahua – including the town’s police chief and mayor. In this scheme, a decorated US veteran and former police officer procured the guns and the mayor (himself a Navy veteran) took $100 for each weapon sold.

Stories like these soak up a lot of press. Who could resist the story of the bungled ATF “Fast and Furious” sting operation that “lost track of hundreds of weapons that were allowed to pass into Mexico in hopes of tracing them to cartel leaders”? But if our attention is drawn towards the lurid details of small-scale smuggling, we can easily lose sight of the big picture: the absolutely gargantuan flow of arms from the US to Mexico.

Since Mexico has comparatively strict gun laws, an estimated 99% of firearms are owned illegally. The majority of these guns are smuggled from the United States: of 99,691 firearms recovered from Mexican crime scenes 2007-2011, the ATF traced 68,161 back to US points of origin, with a similar breakdown for 2009-2014. By using more sophisticated modeling techniques, researchers estimate that a quarter million illegal guns cross the border southwards each year.

Outrage is easy for stories about rogue soldiers smuggling guns, but numbers like these are numbing. And when it comes to US-Mexico weapons sales carried out entirely legally, and with the blessing of Washington, the response is mostly willful ignorance. Past Mexican administrations were often reluctant to pursue formal arms deals with the United States, but in the last few years, there has been a dramatic uptick in “legitimate” trade in arms with Mexico, facilitated by the American government: Mexico spent only $200 million on US military hardware in 2001, but its military spending topped $1.15 billion in 2014 alone (and the trend line is marked). In 2014, the $21.6 million that Mexican authorities spent on American small arms—primarily M-16s and M-4s—represented one of the largest single foreign military sales of such arms in the past fifteen years.

If the details of these sales are reported, they are taken to mark the deepening, inter-American partnership in the war on drugs. Photo after photo of drug kingpin being perp-walked (by Mexican forces toting US-made rifles) are presented as visible evidence of victories in that crusade. Victory is just around the corner; progress is on the march.

Meanwhile, over the last decade, the Mexican police and military have acquired a habit of “losing” an average of 3.5 firearms per day, as the toll in bodies continues to climb.

* * *

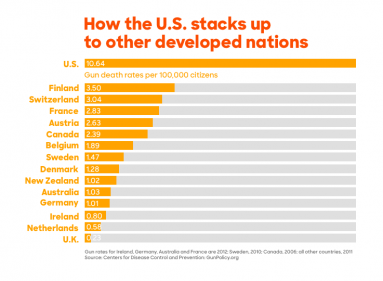

In debates over guns and gun violence in the US, one inevitably hears America compared to “other developed countries.” Our gun violence shames us, but particularly when we place ourselves among the august assembly of peace-loving nations, as when Hillary Clinton tweeted: “33,000 Americans die from gun violence each year. No other developed country comes close.”

But why is “developed country” the frame of reference, and what does it even mean? What is the relationship between one nation’s “development,” the violence it suffers at home, and the violence it precipitates abroad?

Many who define “gun violence” often play fast and loose with the data. Domestic definitions, for example, alternately exclude or include firearm suicides (which can number near upwards of twenty-one thousand per year) depending on the agenda, while shootings of civilians by police (which in the US in 2015 were estimated to be well over a thousand) are rarely counted. This is not what some people mean when they say “gun violence.” But things get even fishier when we look at international benchmarks for gun homicides. Some datasets exclude nations engaged in armed conflicts, despite US forces being involved in an estimated 135 of them. Others define development by emphasizing per capita GDP, meaning “other developed nations” are wealthy nations in Scandinavia, Western Europe, and East Asia, states with populations that are relatively ethnically homogenous; with histories less troubled by settler-colonial genocide, revolutionary violence, and civil war; and with less blatant structural discrimination, rampant extrajudicial brutality, and skyrocketing inequality. These nations are also comparatively under-militarized – in fact, many have enjoyed decades of prosperity under the umbrella of US global military strategy, whether as NATO buffer states against Russia or in triangulations against China.

Still, sometimes even these benchmarks don’t show us what we want to see. At this point, we use “two-handed regression” and simply erase awkward comparisons. In the aftermath of the Sandy Hook shootings, for example, Max Fisher produced a piece for The Washington Post declaring that “The U.S. has far more gun-related killings than any other developed country,” with a chart featuring predictable comparisons to Japan, Austria, New Zealand, and others on the OECD list of Developed Nations. Though Mexico is certainly “developed” per the OECD, Fisher put his hand on the scale: “I did not include Mexico, which has about triple the U.S. rate due in large part to the ongoing drug war.”

This is remarkable. Though fought with US-supplied weapons, fueled by immense US demand, and driven by US policy imperatives, “the drug war” erases our next-door neighbor in a supposedly rigorous assessment of the landscape of American gun violence. Needless to say, Fisher’s chart does not exclude gun homicides which (disproportionately) take the lives of young black men in our own cities, deaths which could be ascribed to the very same transnational “drug war.”

The link on Clinton’s tweet from April leads to an article at her campaign website declaring that “The number of American lives lost to gun violence is more than three times the rate as the next country on the list. If that’s shocking to you, it should be,” and displaying a chart to illustrate this disparity:

The comparison is “shocking,” of course, because these are the nations we compare ourselves to. What if Mexico were on that list, using homicide data from the same sources? Would the Clinton campaign expect us to be “shocked” by that comparison?

Gun violence is an undeniable problem in the United States, but as with so many social issues, our perception of it is constrained by a deeply ingrained chauvinism, an American exceptionalism that is both self-righteous and hypocritical. “Gun violence” is our embarrassment, as a “developed nation,” as civilized, advanced, and wealthy. And so we divide the rest of the world between two categories. There are states with fewer gun deaths than ours, with whom we imagine ourselves as being on a parallel plane of sophistication, and whose superior track record shames us. And there are the squalid, undeveloped hellholes with more gun deaths than ours. We might make billions destabilizing their regimes and flooding their borders with weapons, but our complicity in that violence is not what shames us. Our shame is the fear that “we” might somehow be like “them.”

* * *

Nowhere are the ugly pretzels of this exceptionalism more visible than in debates over “America’s Rifle,” the AR-15. It has often been argued that the AR-15 was meant for the American military, and was never intended for civilian use. The family of the Eugene Stoner (the engineer who was primarily responsible for developing the weapon’s key features), recently made news by asserting that Stoner never intended civilians to possess the weapon. Stoner’s personal intentions notwithstanding, the history is rather more complicated.

Frequently mis-glossed as “Assault Rifle,” the AR in “AR-15” refers to its original manufacturer, Armalite. Of course, the key patent was filed sixty years ago and has long since expired; today, “AR-15” is a trademark of Colt Defense LLC and, over the years, “AR-15” has evolved into a generic trademark, a proprietary eponym like Velcro, Kleenex, Xerox, or Tupperware. Civilian AR-style rifles encompass anywhere between four to nine million weapons used for purposes ranging from recreational target shooting to varmint and predator hunting to simply being kept under beds, in closets, or on mantles. When adopted by the military in a version capable of fully automatic fire, the AR-15 was dubbed, per military nomenclature, the M-16; this has, in turn, birthed a wide variety of variants and successors, from the HK416 used to kill Osama Bin Laden to the M4s and M16A2s carried by American soldiers worldwide.

Many of these rifles have retained superficial similarities with the original AR-15 while also departing significantly from it. A key feature of the original AR-15 design involved capturing some of the gas rushing down the barrel through a tube, and then feeding it backwards to advance the rifle’s cycle of operations. Many ARs still rely on this system (known as “direct impingement”). But some modern successors employ a piston, and thus aren’t really ARs at all. Inevitably in the firearms world, ingenious design innovations frustrate civilian observers and legislators alike. Thus, despite superficial similarities, the Sig Sauer MCX wielded by the Orland shooter is not an AR-15, and a weapon like this is neither technically an AR nor even a rifle: it’s a pistol that you can turn into a rifle (in the eyes of the ATF, illegally) depending on how you hold it. One point, though, is important to emphasize: unless they go through a particularly arduous and expensive licensing process, American civilians can only possess ARs lacking features present in the military variants: most notably, fully automatic fire, but also short barrels and various stock configurations.

The venture which first developed the weapon, Armalite, was a subdivision of an aerospace engineering firm that cannily foresaw a growth market for both military and civilian weapons made from the sleek new materials of the jet-age, like aluminum, fiberglass, plastic, etc. One of its first products was marketed to the Air Force as a compact “survival rifle” for pilots ejecting from their planes, and also to civilian hunters and outdoor enthusiasts, to whom Armalite promised would be made available in variety of exciting colors.

Eventually, Armalite began producing different and more ambitious designs. When the American military began weighing options for replacing its aging M-14 rifles, Armalite entered a fully automatic design into the competition. This gun, the AR-10, fared poorly in Army tests, but it piqued the interest of a general who expressed interest in a smaller caliber version, which would become the AR-15.

To secure lucrative contracts abroad, in other words, Colt’s needed some element in the US military to buy ARs.

Colt’s solution to this quandary is recounted vividly in C.G. Chivers’ magisterial history of assault rifle development, The Gun Colt’s arranged for the vice chief of staff for the Air Force to attend the sixtieth birthday party of the now-former President of Fairchild, Richard Boutelle. General Curtis “Bombs Away” LeMay was a larger-than-life-figure: a race car driver, judo practitioner, hunting buddy of Boutelle’s (with whom he had gone on safari), and, supposedly, the inspiration for the bulldog General “Buck Turgidson” in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. LeMay was also an M-14 skeptic, and a power player in a branch of the military that arguably needed its own rifle for defending its far-flung network of airbases and nuclear silos. Boutelle’s birthday fête was held over the July 4th weekend on his sprawling “gentleman’s farm” in Maryland, a facility complete with an extensive array of shooting ranges. For the main event, LeMay was invited to shoot three watermelons with the new AR-15. As Chivers writes:

“Watermelons were bright and fleshy in ways that water cans were not, and when struck by the little rifle’s ultrafast bullets, the first two fruits exploded in vivid red splashes. General LeMay was so impressed that he spared the third melon; the party decided to eat it.”

Shooting watermelons was a far cry from serious ballistic testing, but it was compelling in other ways. In 1961, LeMay became Air Force Chief of Staff, and in 1962, the Air Force bought 8,500 AR-15s from Colt’s. Just like that, the market opened for sales abroad and at home, military and civilian.

For all its much-vaunted emphasis on “systems analysis” and the managerial prowess of a technocratic “whiz kids,” Robert S. McNamara’s Department of Defense failed miserably at objectively evaluating the AR, and fell prey to wishful thinking and the influence of corporate boosters.

Of course, many of these problems with the weapon were refined over the course of the war. And while historians disagree about the specific numbers, all acknowledge that this brew of institutional failures, design shortcomings, and conflicts of interest cost many soldiers their lives. But these bodies helped plug the gap between faith in American technological superiority, free market innovation, and the wisdom of objective technocrats, on the one hand, and the bitter realities of the AR’s procurement, testing, and deployment process: South Vietnamese proxy troops and unwitting US military volunteers and draftees all served, one way or the others, as the test subjects that made the AR into “America’s Rifle.” The price for an over-hyped American technological innovation was paid not just financially, by US taxpayers, but materially, by our foreign “allies” and unfortunate American citizens serving their country. Back home, entrepreneurial Americans got rich; elsewhere, other, more disposable people – American soldiers and South Vietnamese proxies – got dead.

* * *

Protecting “US interests” tends to go hand-in-glove with arming our proxies: modernization a client states’ military is a key part of “nation-building” and updating small arms, the backbone of any military, is the bedrock foundation. Accordingly, since their first development, AR-family rifles have been a material component of US foreign policy. US authorities first recommended that AR-15s be made the primary weapon for South Vietnamese soldiers as early as 1962, and subsequently flooded the peninsula with them (Vietnamese forces were given over half a million M-16s in 1969 alone). Such initiatives then expanded, with small arms being made available to US allies through State Department-approved sales, foreign military grants (essentially loans earmarked to buy from US manufacturers), or direct provision.

To give a sample, listing the year in which transfers of AR-15s and M-16s are first publicly recorded, and not including repeats: the UK (starting in 1965, for use in Borneo); Thailand and the Philippines (starting in 1966); Laos (in 1967 and onward through the war); Cambodia (from at least as early as 1970); Lebanon (starting in 1972); Jordan, Haiti, and Chile (1974); Zaire, Ghana, and Nicaragua (1975); Israel (at least as early as 1977); Somalia and Honduras (1980); El Salvador, Fiji, Qatar, and Lesotho (1981); the Dominican Republic (1982); Gabon (1983); Egypt (1984); Guatemala (1985); Belize and Northern Yemen (1986); Abu Dhabi (1987); Oman (1992); the United Arab Emirates (1994); Nepal (1999); Antigua and Barbuda, New Zealand, and Mexico (2006); Yemen, Japan, and Jamaica (2007); the Republic of Georgia (2008); and, of course, our client state of Iraq.

Whether arming Asian allies to menace other superpowers, helping repressive regimes quash dissent in Latin America and Africa, or engaging in what Timothy Mitchell has termed “dollar recycling” with Middle Eastern petro-states, America’s arms transfers follow the logic of our interests: our investments in selective regional destabilization, arms-race escalations, and, above all, the flows of capital. Scruples are irrelevant. With even a cursory glance at the list above, the names and organizations of those who have enjoyed American largesse in the form of US-made rifles jump out: in Latin America and the Caribbean alone, they include François “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s government in Haiti, Augusto Pinochet’s junta in Chile, and the El Salvadoran JRG.

* * *

Take a moment, open a new web browser tab, and launch this interactive visualization, which tracks global small arms and ammunition sales for the period of 1992-2010. Year by year, look at how the lines blossom; see where they come to land. America shines like a star, its lines rushing upwards like fireworks; there is no comparison.

* * *

Today, the US remains the world’s top exporter of weapons, and our arms manufacturing firms consistently dominate the list of the world’s largest and most profitable. Precise figures can be difficult to come by: manufacturers adopt ever more sophisticated strategies for shielding the specifics of their sales while clients resist disclosing their purchases. And yet certain trends are clearly visible. Domestic distaste for “boots-on-the-ground” warfare dovetails with domestic commitments to arms-related manufacturing jobs, making it ever more politically attractive to arm foreign allies instead of doing the fighting ourselves. Demand is increasing with the escalation of tensions in hotspots and zones of triangulation in the Middle East and East Asia, along with new markets and opportunities for “cooperation” with India and Vietnam. Indeed, the latter development marks a particularly ironic case of déjà vu: decades after we armed Saigon’s ARVN against the Viet Cong, we have returned to selling arms on the Vietnamese Peninsula, this time to our former enemies: mounting friction with the Chinese makes them eager customers.

We mark this development by celebrating how “peaceful change is possible” and praising the “future [of] prosperity, security and human dignity that we can advance together.”

Against such rhetoric, the figures are stark. In the first five years of President Obama’s tenure, government-approved arms sales topped the total sum of those concluded during both terms of the George W. Bush administration by more than $30 billion dollars. Adjusted for inflation, Obama’s presided (in just five years!) over more arms sales than any US administration since World War II. From 2010 to 2015, foreign purchases of US military hardware rose 118%, and budget requests for grants to subsidize foreign purchases show no sign of slowing down.

Admittedly, much of this increase in sales has been in direct response to the foreign policy misadventures of the previous administration. But this gets at a key point: unlike, say, jet fighters, helicopters, or guided missiles, small arms are low-maintenance, incredibly cheap, and easy to store, transfer, and conceal. Thus, they tend to wander from the hands of a given allied nation’s establishment “arms bourgeoisie”. Small arms are easily seized and turned to new uses. After all, the lethality of ISIS fighters in Syria and Iraq has been dramatically magnified by their possession of thousands of M-16s and M-4s that the US originally sold to the Iraqi army. Some of these are now available for sale to the highest bidder, on Iraqi Facebook groups.

Meanwhile, back home, debates over guns in the US have become inextricably mingled with debates over terrorism, but in a typically blinkered way. Democrats cudgel Republicans with the image of AR-15-wielding mass shooters pledging allegiance to ISIS (despite those shooters’ inevitably all-too-American profile). Senators Chris Murphy, Elizabeth Warren, and Harry Reid have all co-signed the allegation that the GOP “wants to sell weapons to ISIS,” but ISIS, in the Middle East at least, has had little problem acquiring US arms. What matters for political purposes is pandering to the fear that “ISIS” will acquire arms here.

For her part, Hillary Clinton has called for a renewed Assault Weapons Ban, to keep “weapons of war off our streets.” She has also backed a lawsuit by the families of Sandy Hook shooting victims against Remington Arms, whom, the suit alleges, marketed the AR-variant used in the massacre “in a militaristic fashion.” Of course, in her role as Secretary of State, Senator Clinton approved the sale of thousands of assault rifles to our “partners” in Iraq and Afghanistan, including a 2011 contract of $4.2 million for Remington specifically. The outrage is over whose “streets” such weapons wind up on, and where the “militarism” of the arms industry comes to roost.

All of this means that connections between America’s implication in violence abroad and violence at home are foreclosed from the get-go; the more troubling answers to the question of how “a weapon used in Vietnam and streets of Fallujah” ended up in an elementary school Connecticut are easily deferred when blame can be tidily left at the door of a single manufacturer. But we shouldn’t be surprised. The American capacity to wash our hands of blood while simultaneously pointing fingers is nonpareil; when it comes to small arms, our exceptionalism is so much NIMBYism. Not on “our” streets – but yes, by all means, on yours.

* * *

One of the basic things any firearm must do is manage the energy generated when a bullet is fired.

A cartridge’s primer is struck, propellant ignites, and a bullet flies forward down the barrel. Per Newton’s Third Law, this controlled detonation and forward momentum entails a correlative momentum in the opposite direction, the felt force experienced as recoil. Mitigating this recoil is vital to maintaining a shooter’s accuracy, and is thus an important part of firearms design.

Rifles like the AR-15 offer extremely high velocity coupled with comparatively low recoil. Explosive forward motion is ingeniously harnessed, contained, leveraged. Rounds are sent rushing out and forward, again and again, and “kick” is minimized.

In its perfection of these mechanics, the AR-15 embodies a quintessentially American fantasy for engaging the world: maximum impact, minimum pushback, all bundled up in sleek aesthetics and sold at a hefty profit margin. America’s rifle is thus an overdetermined object: the symbol of the violence we visit on others, and which we thrive on exporting. We are accustomed to standing on one side of it, the right side; we expect to have our finger on the trigger, or to be standing behind the counter and taking a check in return. Only when we imagine being on the wrong end of our own icon, when we envision the AR coming home to America, to do to us what it is has done to others abroad, only then, do we recoil.