What do we hear when a woman screams for the camera?

I.

Why censor a scream? In January 1932, a letter was dispatched from the office of Jason Joy, administrator of the then incipient, now infamous Hollywood Code. Joy was writing to Universal’s Carl Laemmle Jr. following a screening of the studio’s forthcoming Bela Lugosi picture Murders in the Rue Morgue. Early on in the film, we hear a woman’s scream: a helpless Parisian girl (Arlene Francis) is witnessing a knife fight between two men. In swoops Lugosi, offering the woman comfort in his carriage. With them we depart the foggy street and fade—not to silence but to a shadow and another scream: The girl in silhouette, her legs and hands bound to a cross, is writhing in agony. Lugosi is Dr. Mirakle, a mad scientist on the loose in the city, and the young girl is his latest experiment.

In his letter to Laemmle, Joy wrote, “Our feeling is that the screaming of the woman … is overstressed.” But it is not the woman’s first scream—emitted as a witness to violence—that disturbed Joy; what prompted the letter is her second scream—when she is a target of violence. “Because the victim is a woman in this instance, which has not heretofore been the case in other so-called ‘horror’ pictures recently produced.” Joy suggests “making a new soundtrack for this scene, reducing the constant loud shrieking to lower moans and an occasional modified shriek.” Laemmle complied, and the letter has since served as an illustration of censorship’s preoccupation with screen violence.

But is the scream violence? If the eye of horror prises open the human body, what interior worlds does the cinematic scream open up that need to be occluded from the range of hearing (and seeing)? In other words, what do we hear when a woman screams for the camera?

Perhaps the single most famous scream in cinema is a man’s—the Wilhelm scream, first used in the 1950s and since then ripped off for high-profile franchises like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, it now circulates among gleeful sound-effects technicians and movie nerds. Instantly recognizable yet still unidentified (we don’t know, despite some efforts, who recorded the original), the Wilhelm scream is a great joke but a bad scream: brief, boring, and bodiless. By contrast, when a woman screams on screen, it tends to be sustained and staged, unabashedly addressed to the technological capture of cinema, a kind of fetishistic elaboration of the woman’s voice in extremis.

The scream is part of a larger range of bodily emissions through which sexual difference is literally enunciated in the cinema: women scream, men yawn and so forth. The image of the scream queen is very much like any other “image of exploited female labor” that Mal Ahern observes Hollywood continuously offering its audiences. Yet what the scream queen produces is both sound and image, or sound as image.

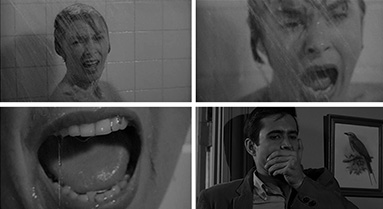

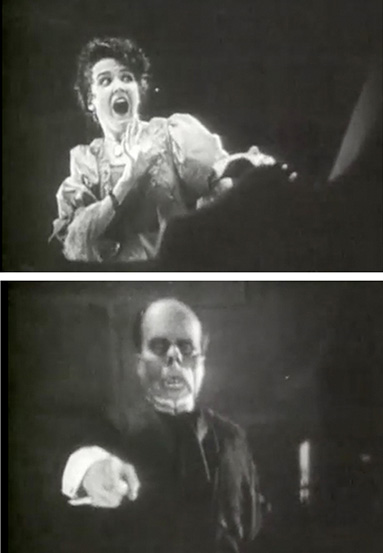

Women screamed in the silents too: Rhona Berenstein, looking at a sequence of Christine from the 1925 silent film version of Phantom of the Opera, notes that the sight of a woman screaming—usually a close-cropped image of her face—indulges and shapes a cultural fascination, the ability to extract from women’s bodies a visible testament of their subjection to the awesome powers of men, whether as filmmakers or film monsters.

But Christine’s scream is visible, not audible—the silent film scream has no grain, to use Roland Barthes’s term for “the body in the voice as it sings.” I am interested in the body in the voice as it screams. The cinematic scream is a particularly grainy catchment area of onscreen and off-screen affects.

For inspiration therefore I use not the silent version of Phantom of the Opera but a moment in Andrew Lloyd Weber’s 1980s shlocky stage-musical version. I’m talking about that moment in the musical’s famous title song, in which the phantom menacingly implores Christine to “Sing! Sing For Me!” For sopranos who have played the part (including superstars like Sarah Brightman), this has meant venturing higher and higher in live performance, forcing the soprano to scale a series of notes that begin at the top of her range and climax with an E6, the first note in the highest register of the human voice. Entering this so-called whistle register, the female voice appears to be vaporizing under pressure, a kind of sublimation of the woman’s body under the sadistic tutelage of her master.

In his book Nuns Behaving Badly, about subcultures in Italian convents in the 17th century, Craig Monson uncovered evidence of all-female choirs that sang bass just as well as they did the part of soprano. The work of producing the high female voice is thus as much physiognomic and muscular as it is historical and cultural: what you hear is the sound of air passing through a matrix of sexual and social prescriptions. Like the singing soprano, the screaming actress joins a transmedia, centuries-long public archive of women’s voices trained to surge, to skirt the edges of the audible and the acceptable, pitched to explode into the air and leave the body behind.

But even as a mechanical recording subject to technological control, the cinematic scream bears the traces of something involuntary, unplanned, excessive—something alive. The scream perversely indexes the minutest secrets of the body from which it departs. The onscreen scream not only serves as an index of visual terror—that is, as an accompanying expression of a woman’s suffering—it is also violence itself, a very idiosyncratic irruption from her insides. In the same way that one can’t predict the exact splatter from a bursting blood squib when producing action cinema, the scream in the horror film, even when scripted and storyboarded and filmed in take after take, is an unseemly profusion of tone, timber, vibration. It is gestural, guttural, grainy affect that cannot be controlled for. Cutting off the scream—censoring it—is a way to render inaudible that which threatens to become audible on the soundtrack: the inside of the woman’s body—her vocal cords, larynx, and lungs at full power, a pornography of pure voice.

Like pornography, horror is what Linda Williams so usefully terms a “body genre,” a cinematic configuration that operates by visceral mimesis, shuttling bodily pleasure and performance between screen and spectator. Insofar as the filmed scream in Murders in the Rue Morgue cues audiences to scream, the request to censor it is a response to that response. Jason Joy is effectively troubled by a scream that alighted not from the screen but from his own body in the screening room: an unexpected echo, an uncanny reverberation of the death rattle. The censor’s is the first in a series of screams that every horror film elicits: Everywhere it goes after it demands and draws more, its screams are often doubled and sometimes, quite strangely, dubbed.

II.

Why dub a scream? Take, for example, the case of I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997). The prolix and much parodied title of the slasher film refers to a note received by four teenagers in a small fishing town informing them that someone knows what they did, well, last summer. Soon, this surprise witness has begun picking them off one by one. But who could possibly know? Whose breath do we hear on the soundtrack and whose silhouette do we see in a hooded slicker? He can hear their conversations and watch their movements, but they cannot see or hear him. At one point in the film, one of the exasperated teenagers (Jennifer Love Hewitt) looks heavenward and screams: “What do you want from us, what do you want?” All-seeing, all-hearing, the killer is a slight incarnation of the omniscient acousmêtre that Michael Chion speaks of in the opening pages of his book Voice in Cinema: a figure whose presence pulsates in off-screen space and ranges over the screen, a godlike eye and ear, himself unseen but able to emerge and extract life—and screams—at will.

Chion develops the idea of the acousmêtre first in relation to the plot of Murnau’s early sound film Testament of Mabuse, in which a booming and disembodied voice speaks to other characters from behind a curtain. When the film’s protagonists finally make it past the curtain, they discover not the person of Mabuse but only a loudspeaker from which his voice issues. For Chion, this revelation of the loudspeaker instructively suggests the ways in which the coming of sound effectively originated off-screen space in cinema by exploiting that which is heard but not seen. I want to make a metaphor of the hidden loudspeaker as incarnating a different kind of acousmêtre—the dubbing artist in the recording studio, whose voice we hear but whose body we never see.

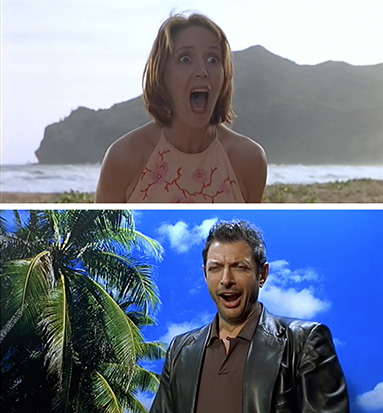

In 1998, Columbia Pictures brought I Know What You Did Last Summer to India, and it was released in both English and a Hindi-language “dub.” Historically, notes Nitin Govil, the dubbing of Hollywood pictures into Indian languages has faced heavy resistance from the country’s domestic film industries, and film producers in Bombay and elsewhere have spent much of the last century informally lobbying for quotas, stringent censorship, and other curbs on the circulation of international film product in India. Thus it is that the dubbing of Steven Speilberg’s Jurassic Park into Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu in the early 1990s serves as an emblem of a significant moment in the history of media globalization. “The sight of dinosaurs running amok and their victims screeching in a local language,” observes Nandini Ramnath, broke new ground and box-office records, sparking a concerted effort to “open up” the world’s most impenetrable film market.

Around the same time that I Know What You Did Last Summer was being dubbed in Hindi, the first convention was held for Bombay’s voice artistes. The Voice Artistes Association was formed in the late 1990s with the aims of enforcing payment of dues by film producers, overseeing contracts, and regulating working conditions and remuneration. For the first time, a wage list was made available in print, which standardized the cost of hiring a voice artist to dub a film by language, budget, and character type (hero, heroine, parallel hero, villain, supporting character, and so on). For dubbing an actress’s part in I Know What You Did Last Summer, a voice artist could expect to be paid approximately 5,000 rupees (about $85). In the dub, these artists can today be heard screaming for their lives (and livelihoods), their voices interlaced with the film’s original score and soundtrack.

Temporally and spatially removed from the throats of the film’s “scream queens” (actresses Jennifer Love Hewitt and Sarah Michelle Gellar), such out-of-sync, out-of-body voices generate a grain that interlaces the sexual division of labor with its global division. When Elsa (Michelle Gellar), on the run from the film’s slasher-killer in the aisles of a department store, chances upon the body of her sister, her throat slit, she lets out a full- bodied scream.

But whose voice do we hear? The wage forms printed in Bombay required that “Names of all the Voice Artistes should feature in the End Credits of Feature Films,” but I couldn’t find them anywhere. I cannot put a name, face, or body to that screaming voice: What remains of the dubbing artist is thus a corporeal trace of her craft. She is, one might argue, the ultimate acousmêtre (or mêtress): heard but not seen, her voice produced onscreen only in its technological mediation, a kind of bodiless presence ranging across the surface of the screen, emerging not from its on-screen diegetic fiction but from its off-screen distributive circuits.

In his work on film sound, Rick Altman has compared sound cinema to ventriloquism, glossing its origins in the Greek ventri, for the belly, the body voice. Just as the ventriloquist asks you to believe that sounds are coming from where your visual attention is focused rather than elsewhere, so “pointing the camera at the speaker disguises the source of the words, dissembling the work of production and technology.” But in the case of the dubbed scream, it is precisely the fact of having the camera pointed at the onscreen screaming subject that disaggregates cinema, bringing into view the unlikely agents of film work. And in I Know What You Did Last Summer this disaggregation is immediate and obvious, in that the “Hindi” scream is tinny, metallic and perhaps too shrill, full of reverb and overlaid echoes, a body obviously screaming inside a Bombay recording booth nested inside a body being hunted down the aisles of a department store in Nowhere, America.

These wordless translations of terror raise further questions: As she watches the film in playback and records for it, is our nameless dubbing artist a spectator or film worker? Does she scream at the screen or for it? To watch her alter ego onscreen is to see a woman fall, rise, run, crouch, cower—a full-blown somatic performance of a scream that now must be intimated by a body and voice proximate only to a recording mike. To watch the scream onscreen is also to see something else: one woman screaming at the sight of another’s slit throat, blood oozing from where her voice should. The slasher film is traditionally preoccupied with serializing women’s bodies as dead waste, creating a deadly sisterhood of scream queens. But as she produces new cinematic materialities and outlives everyone onscreen, the dubbing artist is also the final final girl, perched beyond the frame of the film, her throat, voice, and body intact.