Despite the bleak imaginary landscape of food deserts, urban nutritional politics is all about color

December solstice announces the beginning of the ghetto’s wintertime Rorschach foot game. Is the dark red slush on the pavement frost and blood, or spilled food coloring? If latter, sidestep. If the former, sidestep coolly. The key is to look bored by whatever the red is, and if someone guesses wrong, to look bored. The red slug trail starts at the very top of Myrtle Avenue in Queens and ends in Brooklyn. If you keep following the crimson-red drops down Myrtle and onto Knickerbocker Avenue, you’ll enter an urban a foodscape that is, by the Obama Administration’s definition, not a food desert.

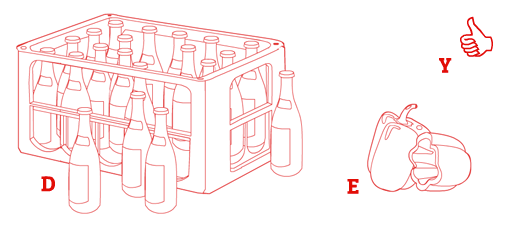

No, this is not a food desert. The streets are lined with McDonalds, Wendy’s, WhiteCastles, and Taco Bells separated by some storefronts that pawn gold and others that will dip just about everything into day-old oil, that wet brass-gold. There is a bodega on just about every corner. It is mere walking distance to a large supermarket adorned with carnival flags waving above old men in bright polyester parkas rolling vanilla-flavored cigars in the parking lot. This is not a food desert. It is not “a low-income census tract where a substantial number or share of residents has low access to a supermarket or large grocery store.” Myrtle Avenue is a food biome the White House has left unnamed.

Popular discourse has left the concept of a “food desert” suspended in a place of no context and incomplete metaphor. Unlike literal biomes, which fall along a geographic spectrum of wet to dry or barren to fertile, the food desert stands alone. When we think about biomes, we think in terms of inverses (hot is the opposite of cold; wet is the opposite of dry) and that’s where it gets strange. What is the opposite of a food desert? A food oasis? A food forest? A food lake?

If we follow the industrial ontology of deserts, we can think of Myrtle Avenue as a nutritional timberline. At the timberline, the forest has dried up and the desert begins--with it, the heavy, hopeless permanence that thickens the air “just past that moment when the desert has become the only reality,” as Joan Didion once described the Sonoran Desert.

Of course, our tour through the biomes doesn’t mean a whole lot until you understand neoliberal magical realism, and the way it presses itself onto bodies. Think about Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of Agriculture pushing the FDA to label ketchup and relish as vegetables in order to justify cutting funds for school lunches. Or think about our Congress’ recent passing of an agricultural appropriations bill that would make it easier to count tomato paste (in pizzas, basically) in school lunches as a vegetable. Gabriel García Márquez describes his imaginary land of Macondo as a place “so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.” Enter a supermarket in a working-class neighborhood and you’ll encounter the same. Cool Whip™, Kool-Aid™, Tang™, and ten-for-a-buck neon drinks do not look like anything else because they aren’t quite real. They’re all a product of modernity’s magic—what is Splenda if not some kind of weird zero-cal devil alchemy? -- and though the new foods that it offers are always recent, they don’t lack names. We simply can’t pronounce them.

The anthropologist Sidney Mintz has proposed that “what we like, what we eat, how we eat it, and how we feel about it are phenomenologically interrelated matters; together, they speak eloquently to the question of how we perceive ourselves in relation to others.” The issues at the core of delicate food debates haven’t ever just been about calories and nutrients and tax dollars. The way the American diet is publicly discussed reveals an ugly underbelly of American cultural practices that we desperately try to cover up through coded rhetorical pyrotechnics. The focus on landscape as culprit—this bogeyman “food desert”— is a diversionary tactic. The phenomenological, political, and uncomfortable crux in the popular food debate is color.

Note the code here: during this year’s Republican presidential primaries, Newt Gingrich publicly denounced President Barack Obama as “the most successful food stamp president in American history,” a racially charged declaration against a black man whose single white mother was on food stamps during parts of his childhood. The other Republican contenders including Mitt Romney scandalized bases with denunciations of welfare and food stamps that painted people of color as fat and lazy freeloaders, despite statistics revealing 70 percent of food stamp benefits go to white people,

Or here: In 2000, Stanford University ran a weight loss program for Mexican American families that categorized foods as good or bad using the traffic light colors of red (no), green (yes), and yellow (careful). Mexican bread was red, so one family moved on to cereal and skim milk for breakfast. They were dismayed that some foods they thought were healthy were in fact “red” foods: vegetable oil, flavored yogurt, peanut butter. One Mrs. Rodriguez praised the program: ''My children, I don't have to be saying, 'Don't eat more ice cream.' They don't want to eat more ice cream. They don't want red lights.''

Red is bad. Red is stop, and these bad Mexican-American mothers need to know to stop and learn how to mother. But red is also Red 40, a good dye to which American bodies have been systematically and corporationally acclimating for decades. Although scientists, behavioral psychologists, and parents have for years been bringing attention to a link between diets rich in artificial food colorings and hyperactivity in children prone to attention deficit disorders, it took until 2007, when The Lancet published a study suggesting the dyes had a significant behavioral impact in healthy children, that the FDA began to listen. In 2011, the FDA proposed a mandatory labeling of foods containing artificial colorants. They also proposed comparing food coloring-related risks to peanut allergies, arguing that some people are simply more susceptible to those allergies, which is not something that has anything to do with “any inherent neurotoxic properties” of the dyes. Just don’t eat peanuts, right?

Not everyone has that choice.

The history of food dyes reveals an undeniably aggressive genealogy of color and violence. In 1856, British scientist William Perkin made the first known food dye, “aniline purple,” using coal tar, an ingredient that’d eventually be substituted for petroleum because coal tar is a tad carcinogenic. In 1950, the FDA banned Orange 1 after too many kids got sick eating candy that Halloween. In 1976, they banned Red 2 (again, because of the persky carcinogenic situation). And in 1986, Brooklyn stores were forced to pull Kool-Aid from their shelves because an anonymous man called in to admit he’d poisoned some boxes with cyanide.

So how does it feel to hear Kraft announce, as it did last year, that it would triple its advertising budget allocated to cornering the Latino market? Three years ago, Kraft created a group called the Latino Center of Excellence at Kraft. Their first focus was Kraft Singles, thin squares of cheese, and it worked out wonderfully. Focus groups found that Latinos bought cheaper products on the whole but were willing to spend more money on the same product if they were told it was made using real milk, something the cheaper brands didn’t offer. Now, the focus is Kool-Aid.

In 2011, nearly all of Kool-Aid’s advertising budget went into the Latino market. Univision and Telemundo airwaves were inundated with commercials designed by advertising firm Ogilvy & Mather that knew to portray images of warm family gatherings that Latina mothers would respond to because they would be “really worried about how fast-paced the American way of life is today,” a Kool-Aid senior brand manager told The New York Times. Kool-Aid sponsored a summertime family TV movie series on Telemundo, one of the two major basic network TV channels to which families without cable have access.

So, shouldn’t we just avoid the goddamn peanuts? We’ve arrived at the new timberline, the point where liberal narratives of agency and body acceptance and choice sometimes get it wrong. Even good things, like the fat positivity movement, when bled pale of color, can be a repackaged alternative of the same old thing, just like Kraft’s invisible Kool-Aid, their new “unsweetened” no-color flavor. The performance of a good, neoliberal subjectivity means consuming and consuming while remaining happy and thin, and the weight loss industrial complex has expertly cashed on this fantastical, impossible imperative—in 2011, the weight loss industry in the United States made $61 billion. It’s one of the more brilliant conundrums of modern-day capitalism.

***

Chains like Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s don’t stock products that contain artificial food dyes. Whole Foods is like a low budget-cathedral—there’s a good-cheer spiritual geometry to the aisles, the stacked specials, even the checkout lines. But the best thing about it is the lighting. Everyone looks good, virtuous, clean. When the local supermarket is clean, it smells chloroformed. The lighting is one dead fluorescent bulb away from feeling like a DMV office.

The problem with the Obama administration’s discursive handling of mounting rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart attacks among Americans is that they’ve gotten away with addressing structural problems like the corporate exploitation of America’s most vulnerable citizens by blaming landscapes like food deserts and fat bodies. For example, the White House announced Wal-Mart’s commitment to Michelle Obama’s anti-childhood obesity campaign with promises to open as many as 300 stores in “food deserts” by 2016. The real food crises in our country has at its heart complicated matters concerning gender, race, class, and education. Dropping down a Wal-Mart selling dozens of heads of lettuce in a poor neighborhood will not solve those problems. It will exacerbate them.

And so it happens that the most important predictor of obesity remains income level. Fast-food companies are dropping obscene amounts on advertising in low-income communities of color, and are targeting children. African-American kids see at least 50 percent more fast-food ads than do white children their age. A full 25 percent of all Spanish-language fast food advertising in the U.S. is from McDonalds and the average Latino/a preschooler will see about 290 McDonalds ads a year. In 2006, 9 percent of Upper East Side residents were obese, compared with 21-30 percent in East and Central Harlem and North and Central Brooklyn, two of the poorest stretches of land in New York. 5 percent of Upper East Side residents had diabetes, compared to 10-15 percent in Harlem and Brooklyn. In these neighborhoods, between 1985 and 2000, the cost of fruits and vegetables increased by 40 percent while the price of junk food and soft drinks decreased by 15 and 25 percent respectively.

We remain at the timberline where liberal narratives of agency and body acceptance and choice sometimes get it wrong.

The fat acceptance movement has found an incredible home on the Internet, where they use personal anecdotes, facts and figures, and rebloggable images to debunk myths equating thinness with good health and fat with laziness or bad health. They have been mostly been right to point out that hatred towards fat bodies is coded as concern for the “cost” to the healthcare system, smokers, while heavy drinkers, drug users, and people with fast metabolisms and bad habits get off the hook. This is because in today’s America, thin, white, and male, are still constructed as ideal default positionalities and to be fat, black, brown, and/or woman is to require more imagination from our compatriots to believe we are human. Fat acceptance activists has been putting up a good fight, but their online biomes would benefit from a more intersectional approach to the spaces fat occupy—that is, it is important to acknowledge that poor black and brown bodies have very different experiences of fatness than their white counterparts do, and the nuance is often lost in Tumblr posts filled with decontextualized pictures of admittedly beautiful fat bodies.

Sometimes fat on a body is normal, and simplistic BMI readings, lady magazines, and everyone else should just go eat cake. But often, it’s not. If some communities have had to see their members’ bodies change over centuries by the poisons forced upon them, defining “pride” and “love” as the only appropriate counterhegemonic affective reactions is an oppressive affective expectation. The literary scholar Elaine Scarry has written brilliantly about human pain and one of her theories it that “the ceaseless, self-announcing signal of the body in pain, at once so empty and undifferentiated and so full of blaring adversity, contains not only the feeling my body hurts but the feeling my body hurts me.”

“My body hurts me”--the “me” in this statement is different from the “me” implied in “my body.” These four four small words reveal a bifurcated knowledge of bodily pain that makes it all the more important to see that neither fat without context nor bones without context be granted rhetorical personhood. Defining no-questions-asked fat pride as some sort of subversive affect is a privileged act of placing some affective experiences above others, and even further, privileging some affective experiences above structural realities. For some, “fat” is a carnal inscription on the organ-and-bone mixed media marvel we call the human body, and like all bodily inscriptions, it does not inherently possess a value, good or bad. This is why variations in corpulence have been regarded so differently across cultures and time periods. Other corporal inscriptions we know to be beautiful depending on context: the crescent-shaped birthmark on your girlfriend’s stomach, the lightning-shaped scar on Harry’s forehead. Others are sad: the calluses on my father’s hands, the makeup caked over the bruise on my neighbor’s cheek. Sometimes inscriptions are given to us by chromosomes or a tattoo artist’s needle, but sometimes they are forced upon our bodies by hegemonic forces. That inscription is more like branding; that inscription burns.