Han Han's half a billion blog followers include Chinese liberals who hope the acerbic young rebel will grow braver or more serious. But Han Han parries with equal parts modesty, disdain and defeat.

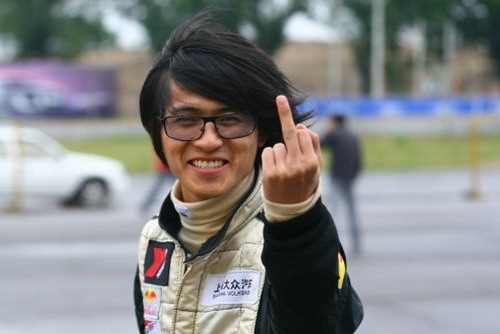

In June of this year, Han Han, one of China’s most popular bloggers, caused an unusually big stir with one of his longer blog entries to date. Entitled “Life as I See It,” it relates some advice the part-time racecar driver recently received from a celebrity agent. It turns out the agent thought Han Han was managing his public image clumsily, allowing strangers to come into his racing team’s tent and take pictures of him while he slept in a fetal position. He also wasn’t bothering to smooth his cowlick after waking up and regularly wore old white t-shirts inside-out and backwards, among other missteps. Han Han rejected all of these as silly and frivolous criticisms, but he did agree he should always keep his fly zipped. Having to keep up with appearances is one of Han Han’s pet peeves, so much so that he refused a meeting with President Obama for fear of being in a room full of poseurs. The post surprised no one, until they hit this rant:

I would like to say one word to those stupid, self-righteous cunts out there: ‘fuck’. That’s right. This will surely get those sanctimonious assholes shaking with rage, ripping me to shreds, yelling and screaming, rolling on the floor. Then, suddenly, they’ll stand up straight and begin to judge—and the solution is to say ‘fuck’ again. Just fuck it. I’m not fucking you, and I’m not fucking everyone in your family, I’m fucking this world, this world where it’s fine to frame someone as long as it’s done in a genteel manner, this world which allows people who don’t curse but who lack ethics to act as moral judges, this world which allows those whose words are clean but whose hearts and deeds are not to be in positions of power, this world where black is white and right is wrong, this world which believes that a public figure, or anyone else for that matter, should under no circumstances utter a single ‘fuck’. Let’s fuck this world upside-down.

Han Han was 29 at the time he wrote that. Adolescence, as the West understands it, did not exist as a concept in Chinese culture until Han Han’s generation discovered it. And like their foreign counterparts, they find it an endlessly renewable source of satisfaction for themselves and entertainment for others. They are therefore loath to let it go. Back in 2009, Asia Weekly, a Hong Kong-based magazine, named Han Han their “Person of the Year” and asked him in an interview, “Which quality do you think this time period lacks the most?” Han Han answered, “All the merits advocated in the students’ textbooks, and what we Chinese pretend to possess, are what this time lacks.” He is now a world away from Triple Door, his debut novel about a student in a near-Orwellian school environment that was published in 1999 soon after he dropped out of the tenth grade, but Han Han’s image of the “rebel as disappointed idealist” has stuck with him.

Boasting over half a billion blog followers and 16 novels and essay anthologies, Han Han, perennial target of China’s government censors, constantly wrestles with what it means to be an effective rebel in modern China. Though no stranger to the Anglophone world (he was named to TIME Magazine’s and New Statesman’s lists of most influential people in 2010), he caught its particular attention with three essays published late last year calling for gradual reform and rejecting democratic revolution in China, which led to charges that he had sold out to his ideological enemies. In This Generation, Allan Barr has translated and gathered Han Han’s posts into a single testament that both gleefully admits to and answers what the writer presciently observed about the dissidents who long to fold him into their ranks, “There’s a good chance you’ll end up as precisely the kind of person you once detested.”

Launched in 2006, Han Han’s blog discusses current events in China, focusing on sensitive topics such as corruption, freedom of the press and economic inequality. Although he was already a best-selling novelist at that point, Han Han’s blog didn’t soar in popularity until the buildup to the Summer Olympics in 2008 when he became much more overtly political and socially conscious. His readers, largely liberal, never gave up hoping that the acerbic, sarcastic young rebel with a supernaturally gifted gut for China’s zeitgeist would over time become more intellectually serious, or at least braver in his assertions.

If anyone holds the honor of being China’s Vaclav Havel, patron saint of Chinese liberal democrats, it would have to be jailed writer and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo. For all his influence, Han Han lacks that kind of moral stature. But could he at least be compared to Lu Xun, the gold standard for Chinese social critics? Hong Kong writer Leung Man Tao and Ai Weiwei certainly thought so. Ai has since retracted his endorsement on account of Han Han’s recent mellowing. Indeed, Han Han has been uncomfortable with the scrutiny and hopes people of a certain political persuasion have projected on him since he burst onto the scene. Whatever their expectations, Han Han parries with equal parts modesty, disdain and defeat.

But what should be expected of Han Han as a rebel? Rebels have two primary desires: freedom, for the individuals who rebel on their own behalf, and justice, for the utopians who act for others. Both drive Han Han. On the one hand, he is an iconoclastic writer who prizes freedom of expression above any other civil right. One of the few opinions Han Han has been consistent on throughout the years is his hatred of censorship. It is what erases his blog posts and felled Party, his literary magazine venture, in 2010. On the other hand, he calls out China Central Television’s penchant to misinform on behalf of a curious citizenry. For his friends and colleagues in the media, especially in film and literature, he pleads the case for wider latitude in artistic creation.

Han Han’s positions on other aspects of contemporary China tend to shift regularly—always within a narrow spectrum, but enough to cause a fair amount of controversy as to where his loyalties truly lie. His secret to keeping the connection with his wary audience lies in his uniquely vigorous and laser-like sarcasm. Han Han claimed in 2008 that he wanted to be an Olympics sponsor so that the Chinese government would actually protect his intellectual property rights for once. On Chinese nationalism, Han Han is at his most devastating. Listing the reasons for why he would boycott French products in response to President Sarkozy’s declaring support for Tibet and his planned absence from the Olympic opening ceremony, Han Han reasoned that a lack of French goods would deprive corruption of its chief currency and help him win races more easily since his rivals drive Citroën cars. When he went to Australia for the World Rally Championship, he chastised the Australians for their lack of pretention, kindness to strangers and concern with protecting spectators and wildlife.

The severity of Han Han’s chosen vehicles for sarcasm indicates irony is not his only gear: there is also a heady dose of perversion. What the state or the sleepy bourgeoisie consider to be good must be corrupted and vice versa. In challenging traffic and vehicle regulations in Shanghai, Han Han identifies them as being effectively anti-poor. Other times, he makes statements that are horrifying on their face but that the reader soon recognizes are commonplace official positions. He pulled no punches with:

Today gas prices are close to ten yuan a liter. But they should be higher still, so high that those troublemakers who are so irresponsible and so indifferent to the interests of our leaders as to set fire to themselves at the slightest provocation will not be able to afford to buy even a single liter of gasoline.

On the controversial Three Gorges Dam, Han Han tells us that those who objected on the grounds of potential drought do not understand that a lake filled with water cannot be parceled off and sold, and local government revenue depends largely on the sale of real estate. This kind of extreme irony must, his liberal readers hope, draw from an unseen reservoir of anti-state radicalism.

Perhaps it is due to this understanding of perverse outcomes for good intentions that Han Han readily subscribes to the more moderate, or conservative (depending on what one compares it to) idea that freedom and justice should not be considered holy grails in China. Pursued to their logical conclusions, they can severely undercut their original intent. Absolute freedom leads to a tyranny of choice that all but the most stubborn rebels would, over time, gladly replace with a tyranny of rules, and utopian justice willingly resorts to self-cannibalism in its relentless pursuit of perfection. Han Han claims that he seldom reads, but he knows enough history to be aware that revolutions are often overwhelmed by the necessity of sacrificing what they initially hold sacred.

His writing assumes that the only way for a rebel to avoid this fate is to forsake the absolute and accept an unsatisfying incoherence to limit the graver consequences of more complete self-contradiction. With a reluctance befitting someone who has made his money on liberal ideas, Han Han advocates for freedom by painting an alternate society in which the absurdities of China’s repressive environment have no place, but he will rarely offer polemics to match. A common charge leveled against him is that he is squeamish about saying anything too objectionable to the Chinese government because he quite likes the life he has built for himself as a provocative celebrity. He has identified and avoided what the censors would regard as serious enough to take away his racing career, corporate endorsements and whirlwind life as a celebrated blogger and media personality. However, it is probably not the case that Han Han enjoys his riches so much as he hates being uncomfortable. In the same interview with Asia Weekly, he had this to say about his prolific, but often impotent, critics in the Chinese intelligentsia:

If one day [the literati] really were to change something quickly, they must have been literati selected by political interests. If you think of everything as fun, then you won’t feel so powerless. The literati’s purpose is to make everyone in the world feel powerless, including the president or the chairman, and that makes a better world.

Vaclav Havel’s character of the greengrocer, who curses both the corrupt authorities and the radicals but decides to publicly side with the former because he would rather be a dutiful citizen than a long-suffering rebel, could not have embodied this skepticism of reformists any better.

So great is Han Han’s fear of widespread unrest that he published three essays last year, all included in This Generation, that passionately call for caution and restraint in the face of democratic pressures. He strongly believes that the Chinese are too fragmented in their interests to maintain the solidarity needed to first undertake a revolution and then govern. More importantly, “In a country whose social makeup is increasingly complex—the final winners in a revolution are bound to be ruthless and cruel.” Han Han cannot stomach a revolution in the name of justice if it adversely impacts any strata of Chinese society, Communist Party officials excepted.

If this book shows any sort of trend of Han Han’s development over the last few years, it is that he has actually become a more engaged activist at the same time his political self-righteousness has died down. The sarcasm is tempered, replaced by a thoughtful discussion about the current state of Chinese society and his hopes for its future.

And, yes, Han Han does believe that democratization is inevitable in China. He bridges the apparent gap between his short and long-term prognoses by claiming that in order for democracy to truly be sustainable, there needs to be a solid system of education, a civic-minded culture, and the rule of law, and that each of these is earned with time and gradual reform. What Han Han has not considered is that the very same cultural conditions that make revolution impossible will also block concerted efforts for incremental change.

In the final post of 2011, which closes This Generation, he declared once again that he would henceforth unfailingly be himself and not appease anyone else’s expectations. What disappoints Han Han most is that many Chinese people have become so incredibly materialistic and self-centered as to render collective action impossible, and yet they still do not share his individuality. Han Han is not asking for Western-style democracy—he wants Western ideals with a Chinese democracy. It may be the ultimate solution, or yet another perversion.

Over ten years ago, Slavoj Zizek reframed Vaclav Havel’s political decline as a subversion of the Velvet Revolution’s democratic and socialist values in an essay for the London Review of Books. Interestingly enough, Zizek recently argued that an idea and its negation may co-exist (in what he terms “para-consistency”), and the dynamic movement created by the tension is capable alone of generating substance. A rebel at war with himself may ultimately be more effective than one who places coherence above action. In keeping with his penchant for gratuitously owning up to whatever sins he has been accused of, Han Han would eagerly agree that the point of his mercurial and contrarian style is to create something out of opposites, as Zizek would put it, that cancel each other and amount to less than nothing. But Han Han may be more on target than he thinks with his deliberate elusiveness. Where he does not bother to correct his contradictions, we are introduced to the ideal of Western values within a Chinese democracy, a cynical man who will not let go of his innocence and, most promisingly for himself and his chosen subject, a rebel whose most fundamental desire is order.