Modern Japanese crime thrillers give a seamy voice to societal discontent

I have a suspicion that Japanese works often get dumbed down during translation. Why that is I don’t have the authority to say, except to note that with vastly different grammatical structures and subtleties in language, particularly in social contexts, properly conveying the material can be a difficult balancing act. The feeling that something is lost is particularly apparent in works like Hitomi Kanehara’s Snakes and Earrings, which from the opening paragraphs bears the distinctive mark of that awkward, distanced dialogue so common among said translations, or Natsuo Kirino’s Real World, with its substitutions for teen slang—so many “dudes” that we wonder if the story doesn’t take place on a California beach. Or Kirino’s novel Grotesque, shortened and censored to the point where characters and their motives appear shallow. As a result there is a clunkiness that in most cases I’m not quite sure who to criticize for, if anyone at all.

All of this simply to say that it’s neither the translation nor the writing itself that draws me to the genre of Japanese crime fiction in the first place. It’s the emotional pull lurking under the occasionally flat text, as well as the notable proliferation of female authors who, within traditionally masculine parameters, have gained a foothold in the telling of darker psychological narratives. Kirino, hailed in the States as the quintessential author of Japanese feminist noir, has struck a chord in Japan, and what sets her apart is not about her style but in what she expresses. In an interview with Theme Magazine from 2007, she shares what readers have told her: “Thank you for writing what I feel.”

A housewife assists in dismembering the body of an unfaithful husband, a female office worker plots a traceless murder, and a group of schoolgirls help a high school outcast escape arrest for matricide. They derive no benefit from their stereotypes; they are too hard-bitten, too unattractive, too young to be taken seriously, or too old to be socially desirable. Their stories are usually ignored, and their voices yield contempt. In the U.S., we like stories of horror or violence that speak to concerns about sexuality and emasculation, but we do not have as much interest in female antiheroes. There exists a fine yet definite line between the serial killer protagonist who gets to head a premium cable show and the twisted fantasies of a woman steeped in a lifetime of frustrated ambitions.

The nameless narrator of Grotesque, for example, is an extraordinarily difficult character to sympathize with, and an ugly one to get lost in. Her jealousy of her beautiful sister, a prostitute whose murder forms the backdrop of the story, is all-consuming (it may be worthy of note here that prostitution is almost portrayed as a form of empowerment—if not for the fact that both prostitutes in the novel are murdered during the course of their work). She is petty, spurred on by injustices and humiliations both real and imagined, fatalistic about any attempt at being recognized as a person of worth. She draws the reader into her ugly world, for the worse, and directs our stare into the wound left by a lifetime of resentment. “Was it my lot in life,” she muses, “to stand forever on heaven’s shores watching the glittering swirl of celestial bodies on the other side?”

This is a side of Japan that isn’t often shown—the lives of women who aren’t cute or child-like, the ones who can’t afford to depend on anyone and aren’t really liked enough anyway, who work on the fringes of society and look forward to the bleakest of futures. We’re familiar with men whose aggressive efforts to attain a proper, virile masculinity reveal them as weak and pathetic; we know stories of children who were never nurtured by kind, broad-minded adults, who grow into physical and psychological abusers in their own right. While these narratives have entered the mainstream, a more resistant barrier exists for women who are neither helpless victim nor sultry femme fatale. They are slotted into a different role, one that exists to dismiss them: the bitter woman.

Resentment is classified as hostility toward another group, a privileged group perceived as being responsible for one’s feelings of powerlessness or inferiority. The feeling is chronic, indirectly expressed, bitter. It wishes to even the scales by bringing others down. A search for “bitter women” online comes up with a bevy of results that imply, even today, that women have a reputation for it. Angry Men and Bitter Women. Are You a Bitter Woman? Why Are Some Women So Bitter? Two of the results on the front page feature black women.

***

As with Grotesque, Miyuki Miyabe’s All She Was Worth features a twin set of murders, both committed by women motivated by their limited financial mobility: one weighed down by Japan’s credit economy and legal insistence on family ties, the other by dependence on her husband’s income. The inspector investigating the case is limited by bureaucracy, his own worth lowered when he has to take medical leave. There is a common theme throughout Japanese crime narratives: an inescapable social structure, a culturally endorsed sense of inevitability, and a sense of being the protruding nail that (so goes the phrase) is hammered down. In wider readings this type of discontent is not restricted to Japanese women. Some may be more vulnerable to this system than others, but to maintain such vast class imbalances, no one can be immune. And murder, in a system that fosters spite, is a tantalizing retaliation.

Spite, as opposed to resentment, is expression thrown outward, externalized, weaponized. There’s a lot to be said, that has been said, against it. Yet spite can be useful as a temporary motivator, a fallback that is tough if not noble. We know that the spiteful are not popular, they are never loved, and maybe they never have been, and that’s what makes it a lifestyle—a perpetual reaction against a hostile, unloving world. It’s better than lying down, accepting circumstances, and waiting to die.

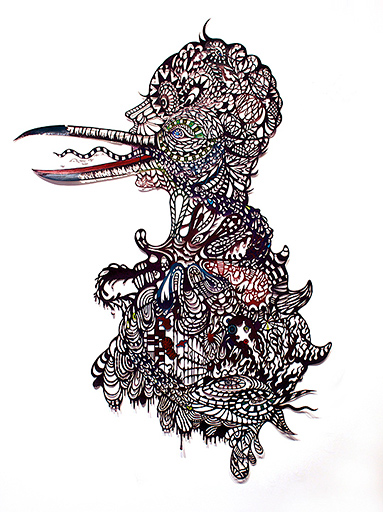

While it may not be a wholly sustainable source of power, it is a form of power—a repressed form, a distorted, deformed, mutant offspring of it. The women of today’s Japanese crime fiction do have a dark, swirling energy that makes them impossible to simply wave aside. Held back, their spite grows tenfold and is hurled out at the world in short, violent outbursts whose effects reverberate; but society, as ever, refuses to acknowledge this seething undercurrent. Things in the dark are left to the dark, dialogue is cut short, and even those in their clean offices and expensive homes suffer for it.

The resentful, according to Nietzsche, become filled with pent-up spite. They become secretive and sly, creating secret enemies, scapegoating others, becoming ever more clever and vindictive in order to sustain themselves. They create, by imagining every kind of retribution; they deny, by bottling up and containing all the cruelties and exercises of power that elude them. Nietzsche scathingly disparaged the morality this produces, which forms a basis for the dichotomy of good and evil—the implication of such a setup being that, eventually, the wicked group will one day face divine retribution. But the bitter woman of the Japanese crime narrative does not believe that God’s wrath will punish the privileged. She acknowledges her own filth as well and maintains that she does not care; she does not believe in an ultimate moral vanquishment and doesn’t fight for one. There is, ultimately, no moral climax, no clarion call to something like justice or pity. She is satisfied in being a cancer to society solely by remaining alive and poisonous. She is its dark mirror—if not divine, then at least eternal.

In an archetypal sense this is something akin to the wrath of Izanami, punished for her gender and trapped in a defiled realm; or from Western myth, the wrath of Lilith, whose resentment is the envy of the dead toward the living: the hatred of their joys, and the fact that they hardly seem to think twice about the matter. Their spite stems from the fact that the living continue to keep on living, ignorant to their trials and contributions, without them.

Kirino, Kanehara, and Miyabe channel this destructive power back into something creative, refusing to add romance or any positive insight, and in doing so succeed in making their readers feel as uncomfortable as they do. It’s a deep, nagging discomfort, the kind that sticks like a barb long after the stories are over. The character in question simply disappears from our view when the novel ends: perhaps she is dead, perhaps she has moved forward, perhaps, somewhere, her life continues the way it always has.

It’s a disturbingly easy vanishing. Even if someone did care for her, as with teen runaway Kiririn of Real World or Shoko Sekine of All She Was Worth, she does not believe it. She has already given up on faithful attachments, jaded as she is by warped perceptions of a person’s value. It’s the basis for a crime like Sekine’s murder—the belief that no one would care for a loveless woman, that no one will go looking for her after her disappearance. “No emotional attachments,” the narrator notes, “no orders from anybody. She’s like a wall covered with paper in a bright floral pattern: underneath it, reinforced concrete. Impenetrable, as solid as they come. An iron will to survive. For herself and no one else.”

That’s what becomes safe for her, what’s comfortable and familiar. Anything else belongs to that other world, that seemingly bright, happy world that she’s not allowed admittance to, and which she eventually refuses entirely. Accustomed to her combative existence, she grows inwardly ever more distorted, ever more isolated. If the world does not care for her, after all, then there is no reason she should care for it.