Headed for a reboot, DC's comic Hellblazer will have to find a new politics in a post-Thatcher world

Horror is political precisely because the realm of the political is horrifying. Detective Comics recently published its last-ever issue of Hellblazer, one of the most important graphic novel series ever written. The iconic horror noir comic, shortly to be rebooted as a straightforward superhero franchise, starred a left-wing anti-hero, John Constantine, who routinely tussled with both run-of-the-mill Satanists and Margaret Thatcher. Constantine is the most charismatic “alternative” character published by mainstream comics, a one-man argument for a comic more influenced by J.G. Ballard and indie film pacing than superheroics. The comics blogosphere has reacted to the comic’s cancellation by writing eulogies to the character’s charisma. In this version, John Constantine is an handsome, exotically British rogue who chain- smokes Silk Cuts, always “knows the score” and has a lot of sex in squalid little horror stories. But this slick, atavistic, frat-guy incarnation is undoubtedly exactly what will be preserved when DC relaunches the comic — once a trenchant critique of consumerism — as a PG-13, family-friendly commodity ready for the rumored Guillermo del Toro movie tie-in.

What will be lost is precisely how uncool the first issues of Hellblazer were, how vitriolic, melancholic and spiteful, how negatively charismatic, how difficult to read. Hellblazer is one of the ugliest mainstream comics I’ve ever seen. Page after page writhes with body horror. The comic’s many delights include sex scenes between lovers whose skin has been peeled off, a man’s body inflating with insects, and skinheads fused together into a horrific four-armed hooligan golem. It’s amazing that DC — the publisher of Superman and Batman — ever even agreed to it. And yet the horror in the early issues of Hellblazer is characteristically unspectacular. Rarely inspiring the sublime dread of, say, a Cronenberg movie, the body horror in these comics is mundane, almost quaint. This is because Hellblazer aspired to capture the horror genre in service of left-wing allegory. It was no diversionary spectacle,but simply a straightforward presentation of the horrors of a triumphant far-right. Activist in orientation, bohemian in sensibility, Hellblazer was virtuously unpleasant.

John Constantine is probably the only mainstream comics character deliberately designed as a fusion of counterculture and leftist politics. He possesses a rather unusual origin story. In 1985, the three artists of the comic Swamp Thing — Steve Bissette, John Totleben, and Rick Veitch — wanted to draw a character who looked like Sting. By ‘Sting,’ they meant not just British post- punk, but the more menacing Sting of alternative film and television: the mod hooligan of The Who’s Quadrophenia and the devious Sting of Dennis Potter’s Brimstone and Treacle, a character that Sting himself imagined as the Devil. They knew what this new character, John Constantine, would look like, but who would he be?

Swamp Thing writer Alan Moore imagined John Constantine as a class reversal of the fantasy wizard archetype. Most genre sages belong to the upper class: Doctor Strange is a Doctor and the Jedi Knights and Middle Earth’s Elvish gentry have British accents, unlike the rabble whose fates they augur. Constantine, instead, was a blue-collar lad, more like an amoral noir detective than an omniscient ascete like Gandalf. He was a chancer, hustling, playing both sides against the middle and making it up as he went along. In fact, one of the character’s central traits is his fallibility. The typical Hellblazer plot features John Constantine improvising his way out of masochistic despair to achieve a glorious, qualified, lamentable victory. The character spoke a working class, demotic British English rarely heard in Anglophiliac Downton Abbey-loving American media (Constantine responds to an arcane prophecy by saying, “Bloody hell, I’ve read better horoscopes in the Daily Mirror!”) and fronted both a punk band (Mucous Membrane) and an all-subcultural cast that included Rich the biker, Judith the pink-mohawked punk, and Emma the bohemian painter.

For writer Jamie Delano, who created Constantine’s own comic, Hellblazer, and wrote the first 40 issues, the Thatcher-Reagan consensus was a far more terrifying apocalypse than some prog-rock Ragnarok. As Delano wrote, “the late Eighties were a grim time in Britain for those of my (then) thirty-something generation and cultural inclination — facing a third term of the Thatcher Reich which seemed to have steamrollered the counter-culture dreams of our adolescence and obliterated our twenties."

A stoner son of Northampton like Moore, Delano created Hellblazer’s tone of romantic fatalism, most of its tropes (most notably, Constantine’s dead friends as guilty ghost chorus) and the comic’s most important supporting character: Constantine’s friend Chas Chandler, a blue- collar cabbie like Delano himself, who wrote his scripts at night. He also wrote Hellblazer as a left-wing political diary. In Delano’s Hellblazer, yuppies literally are demons. They gamble on an underworld stock exchange. Vietnam vets shoot up Midwestern American towns. British royalists are thwarted by a coalition that includes two eco-feminists and a queer journalist, but no magical force can prevent the election of Margaret Thatcher.

Delano didn’t really consider himself a genre writer. Rather, Hellblazer represented an attempt to use genre fiction as a way to more accurately describe right-wing ascension. Thatcher, after all, had come to power when a grave-diggers strike had left corpses unburied across Britain. “I had begun to think that perhaps the popularity of the horror genre during the last decade was in some way a product of the hellish zeitgeist,” Delano wrote in the introduction to the first Hellblazer graphic novel. The comment calls to mind the Marxist dicta that social formation determines aesthetic forms. “No such luck. Greed and self-interest prevail and our collective subconscious will continue to squirm and extrude guilty nightmares in response. So fill up your inkwells with blood, chaps. Sharpen your bone stylus and stretch your human-skin vellum.”

Delano’s prognosis is neoliberalism and his response is horror. Hellblazer’s political grotesquery is not that far from Bolano, Kim Hyesoon or Raul Zurita, and the comic’s subcultural cast could be a group snapshot at an Occupy General Assembly. Its supernatural body horror — perverse, bloody and romantic —is our dominant genre today: consider the Walking Dead series, Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, the rise of zombie metaphors used to describe the subprime mortgage crisis.

Comics, however, have largely become about themselves in the past few years: the endless origin stories rehearsed in Hollywood blockbusters, the continuity obsession of writers like Dan Didio, and the valorization of “the story” itself by writers like Gaiman, Morrison, Moore, and Ellis. As comics culture has become more mainstream, the room for oppositional comics is restricted. Hellblazer now sells a third of what it did in the 90s. Its horror, once politically motivated, degraded into a nihilism so gory and sleazy that artise Eddie Campbell publicly balked when he had to write the comic. Constantine himself became a commodity of nerd fandom. You can buy a collectible Constantine statue, watch him interact with spandex-wearing superheros in his new title, and even watch the 2005 film adaptation Constantine, in which Keanu Reeves plays the title character essentially as a charmless Christian policeman who possesses magic powers and nicotine gum.

One could hardly be surprised when writer Warren Ellis held a symbolic funeral for Constantine a few years ago in his own comic, Planetary. The argument seemed to be that Delano’s anti-Thatcher politics were no longer appropriate. It’s worth noting that Delano himself handed in his last script the day Thatcher left office. Since then, no Hellblazer writer has grappled with how to imagine an oppositional space in the age of nominally left-wing conservatives like Clinton, Blair, and Obama.

Stronger on ire and spectacle than plot, Delano gleefully inflicts the suffering of the global south on Manhattan socialites and Tory ministries. In that first Hellblazer arc, an African hunger demon called Mnemoth wreaks havoc on New York and wealthy Manhattanites begin to eat everything in sight — raw sausages, tablecloths, gemstones, a woman’s dress — before literally starving to death. Anti-christian and anti-bourgeois, the story gleefully conflates famine in Rwanda and Darfur with the more materialistic hungers of Western consumerism. When I began reading Hellblazer as a teenager, it was the only comic that I felt uncomfortable reading on public transportation. I was worried that bystanders would see me looking at these violent, hideous images, but re-reading Delano’s run, it seems unmistakably about forcing the reader to go from being a voyeur of genre horror comics and to become a witness of her own terrifying political conscience.

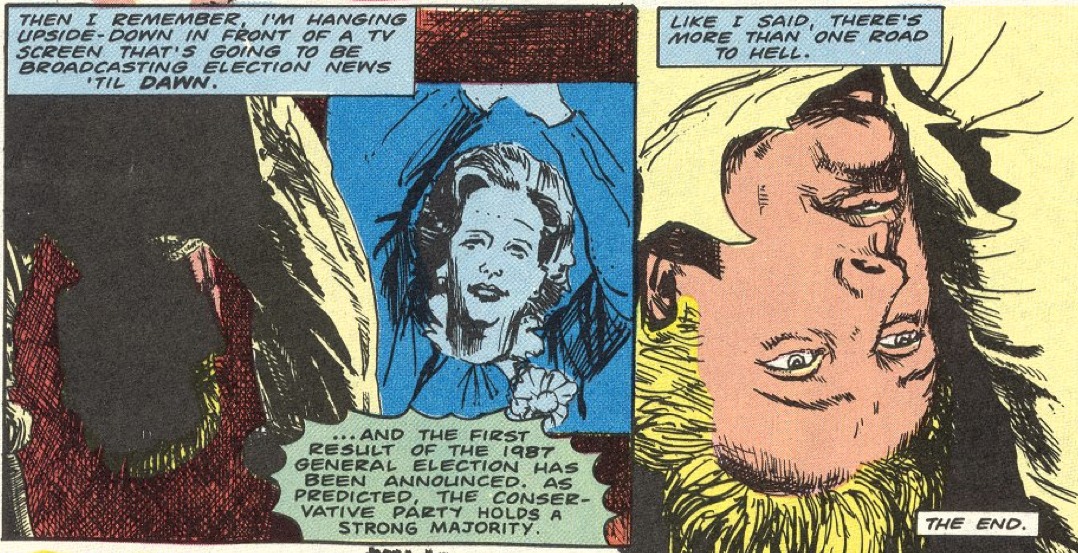

Thatcher literally campaigned on the slogan that, against triumphant neoliberalism, There Is No Alternative. And if no other alternatives exist, then the only space left over belongs to areas that do not exist on the map: transgressive subcultures, like bohemians, eco-hippies, queers, people of color. In one issue, Constantine causes a stock market crash in hell and vanquishes demon yuppies clad in jogger outfits and Savile Row suits, but the story ends with him dangling upside down, stuck watching the Iron Lady deliver her re-election speech on television. Early Hellblazeris a chronicle of the powerlessness of the 80s-90s Anglo-American Left during the Thatcher-Reagan era, imbued with that fatalistic, characteristically left-wing sense that one’s political agenda will be forever unconsummated and deferred. There is, as Constantine himself observes, more than one road to hell.