Carlos Fuentes's final novel takes on the sociopolitical problems of modern Mexico.

Adam in Eden is a novel about drug-trafficking that doesn’t talk about drug-traffickers. It is a novel about the Garden of Eden that hardly acknowledges God. It is a political novel free of rants and rhetoric. And it is a funny novel, with a sort of hidden poignancy: it makes you laugh until, upon closing it, you find yourself no longer laughing.

It is also the last published novel from the celebrated Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, a man who wrote almost exclusively about Mexico but was once called into question for lacking a true Mexican identity. And inasmuch as all of his novels have been forays into the history of Mexico (one way or another), Adam in Eden goes the furthest, outlining in no uncertain terms the sociopolitical situation as he sees it: The country is corrupt, and only through corruption can its ills be healed. Fuentes himself called the book “novel-reportage” and “very journalistic.” Yet it reads like Vonnegut, the kind of satire-candy that bloodies gums.

The jokiness and nonchalance of tone can be a little irritating until the reader relaxes into Fuentes’s “ironic disposition.” This “paradoxical weapon” is what helps us process what the author decides we cannot deal with: truth and Mexico — or the truth about Mexico, at least Fuentes’s version of it. In lean (but often repetitive) prose, Fuentes details the commercial and domestic woes of Adam Gorozpe: prominent businessman, husband of a corpulent and flatulent ex-beauty queen, and lover of a mistress he calls L. Gorozpe is confronted with his double, a short and portly supervillain “with a face like a cooked ham” who has been put in charge of public security — “or what little remains of it.” Góngora makes love to Gorozpe’s wife and begins a reign of state-sponsored (in that he-is-the-state-and-so-can-sponsor-it) terror, imprisoning and killing at random, making arrests of innocents and small-time crooks in order to let the real bad guys, “the gang and cartel leaders, the gunrunners, and the criminals who extort and kidnap,” go free.

Adam in Eden is a portrait of a country imperiled, in which the sons of gardeners are murdered and housemaids slapped (all senselessly) to preserve an order that has given a very few possession of all the wealth, power, and pursuit of happiness. The result? “We have lost our faith in everything.” The political parties are too preoccupied with infighting to solve any of the several dozen problems facing the United Mexican States: border troubles, drug trafficking, the price of oil, corrupt armed forces, joblessness, and the “need everywhere for construction and reconstruction: highways, ports, dams, development of the tropics, agricultural development, urban renewal.” The putative problem-solvers merely compound problems, spawning others less easily fixed.

The novel that could so easily be shouted from a soapbox concerns itself with smaller matters. Consider Gorozpe’s refrain, which builds momentum from simple query (“But why are all my employees still wearing dark sunglasses?”) to bulleted list (“The black sunglasses worn by my associates. My poor Priscila’s romantic rebirth. The military menace of Adam Góngora.”) and finally to litany (“The threats accumulating like clouds, Góngora, Priscila, Abelardo, the criminals, the injustices, the insecurity, Jenaro Rubalcava, Chachacha, Big Snake, my father-in-law, the Boy-God of Insurgentes, my associates wearing sunglasses in the office—”). The refrain gains intensity as Gorozpe continues not to act. Instead of tackling the bigger problems, Gorozpe’s “most immediate concern” remains “how to work out my screwed-up relationship with L.”

When Gorozpe’s brother-in-law, the wayward aspiring writer cum spiritualist toadie who declaims the ugly truth in the first place, asks him about the soul of Mexico, Gorozpe appears unconcerned. Rather than trumpet any grand pronouncements, he begins to hedge: “The soul… Well… There’s still time for that…All eternity, after all? Unlike the fate of the nation’s soul, my situation at home needs urgent attention.” For Gorozpe has smaller — and, according to the novel’s hierarchies, more important — things to deal with: “Priscila: Abelardo’s sister, Don Celestino’s daughter, Góngora’s (likely lover), and my wife before man and God…” Small potatoes, according to the prophets and the politically outraged — but very much Gorozpe’s bigger beef.

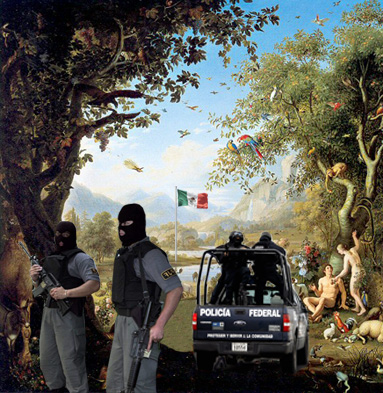

Adam in Eden is no polemic. By concerning himself with the quotidian, with the particular and interpersonal, rather than the current sociopolitical turmoil in Mexico or the corruption of the world, Fuentes subverts expectations of his narrator, whose frankness and candor steer us through factoids and newspapery bits and back-door feats of allusion until, through comprehending the situation of one man, we comprehend his country. Because his narrator is selfish, Fuentes, steering the narrative on a straight course through the narrator’s personal realm, forces our focus also to narrow. The state of greater Mexico is secondary, and becomes visible only in the background, as if by accident of excess paint and not design — as if it is nothing more than the playground for a fallen man.

Four lines from Paradise Lost figure as the epigraph (a little obvious, perhaps, for a novel about an “Adam” — in Eden or anywhere else). There is a henchman named Big Snake, a Boy-God Holy-Boy preaching on the corner of Insurgentes and Quintana Roo, and a grey-veiled Virgin of Guadalupe. There is even a mistress coquettishly named L., who calls to mind a certain first wife of Adam. Yet, as the aptly named friar Filopáter tells Gorozpe, his sin is not Eve: “It’s the apple. And the apple is greed, rebellion, pride.” Gorozpe must take down the villain Góngora, pull off his blinders (and the dark sunglasses of his crew) and confront what plagues the country. The task that becomes the former’s “moral commandment” is to defeat the latter at his own game “by employing, better than he can,” greed, rebellion, and pride.

The slow boil of Gorozpe’s inertia, plus the endless rote refrain of his quotidian concerns, justifies his final acts. These are more satisfying for Gorozpe's initial lameness and his tendency not to stand up too prominently for anyone or anything. Góngora, then, is not merely an evil foil, the foe of modern Mexico; he is an adversary worthy enough to drag our hero out of apathy. Gorozpe’s actions are ultimately just as much about revenge as they are a ploy to save the aforementioned (and scoffed at) soul of Mexico.

Fuentes renders Gorozpe as a second Salieri, forced to confront an impish nemesis whose tactics he must fear and therefore credit with a certain respect. (“‘He is a genius!’ I despair.”) The villain’s name, Góngora, references the 16th century poet Luis de Góngora. And Fuentes compares the hero Gorozpe, despite himself, to “a latter-day Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas,” whose rival conceptismo strove to do what Fuentes does so effortlessly against the Góngoras of the world, which is to say, through word play, wit, and simple style, convey as much and as many possible meanings in the fewest words. (By the same token, Gorozpe’s brother-in-law Abelardo may well be named for that great 12th century Realism-defeater and rationalizer of religious truth. Abelardo may be made to look ridiculous, but he is a true believer.)

The novel unfolds like highly textured fabric, heavy as expensive drapery, beginning with a fugue of questions and continuing at a fast pace, even though nothing really happens until the end. In a world where “we employ violence without revolution, peace without security, democracy without violence,” where everything is falling apart and there’s no harmony, “the forces of order only create more disorder.” Because there’s “no authority” anymore, Gorozpe must seize it, must take control of his own narrative arc, must be the genuine order in his world and in ours. He must bombard Eden with a cleansing violence and stand guilty in the ashes. The novel closes with a restoration of hope and faith for most, but also a PR campaign launched from the pulpit of Insurgentes and Quintana Roo that guarantees that the criminal punishing of the criminals will be seen as “heaven’s revenge,” “an apocalypse live and in person.” This is just the sort of snarky flip for which Fuentes is famous. Heaven didn’t intervene to save them all; Gorozpe did, and he is godless — but who believes in heaven anymore? A comet blazes across the sky (or several comets are always blazing) and the priests and astrophysicists will continue arguing over what they mean.

This is not a book about losing Eden so much as a book about regaining paradise — by force. Gorozpe confronts the line between lies and truth by lying better than the other side in service of truth’s exposition. As a narrative feat, the approach works mainly because we do not expect it from our narrator. The vicissitudes of globalization, of the things we get away with, the knowledge, the greed, rebellion, and pride, are neutralized in one covert final opus sensibile of a lucky but otherwise unextraordinary businessman, a zany parable that might well stand in for Fuentes’s last will and testament. The moral of the story: Good people must intervene to save our souls; the ends in this case justify the means; and, ultimately, there may still be hope.

The penultimate note, however allusive, strikes a secular major chord. Order (and Eden) can be restored, but not by God. Power corrupts and deceit is wrong, but when employed in measured doses by a desperate man who’ll not take credit, they can fulfill a dying author’s wish and purify a country. It will be a secular redemption, of course, but the people will bow before their virgins and their crèche and thank their iconography all the same. Then Fuentes can begin a novel with a sly confession — “I don’t understand what happened” — and end it with a man named Adam killing one Snake and his gardener taking another home to nurse. An unlikely narrator pulls off an act as catastrophic as it is unexpected, a farcical barrage of sudden action with a strikingly uncomplicated final resolution — a subdominant cadence, if you will.

E. Shaskan Bumas and Alejandro Branger’s jaunty and often colloquial translation might be trying a little hard at times to render Fuentes’s innovative and expressive Mexican street slang into English (“not-so-hot tamale”?), but their rendering preserves the playful quality of his prose (“the one who is narrating, the one who is not me, but who I once was”). The translators’ voices disappear completely whenever Fuentes’s finger splits the page to address his reader more directly, the reader who must always end the novel, wresting it from the author’s hands: “‘And what does all of this have to do with Adam in Eden, the novel you’re reading?’ ‘Everything and nothing.’” We continue to outsmart each other, writers and readers, narrators and nemeses, translators and Mexicans and denizens of Eden. A noble narrator declaiming certain truths about the state of Mexico would seem preachy where an ignoble one does not. Gorozpe is imperfect, a little petty, and that's precisely why he is Fuentes's chosen instrument for this last (wishful) act of social change. Fuente’s final character, his last man, is the first man.