If witches didn't exist, early 20th century reverend Montague Summers would have had to invent them

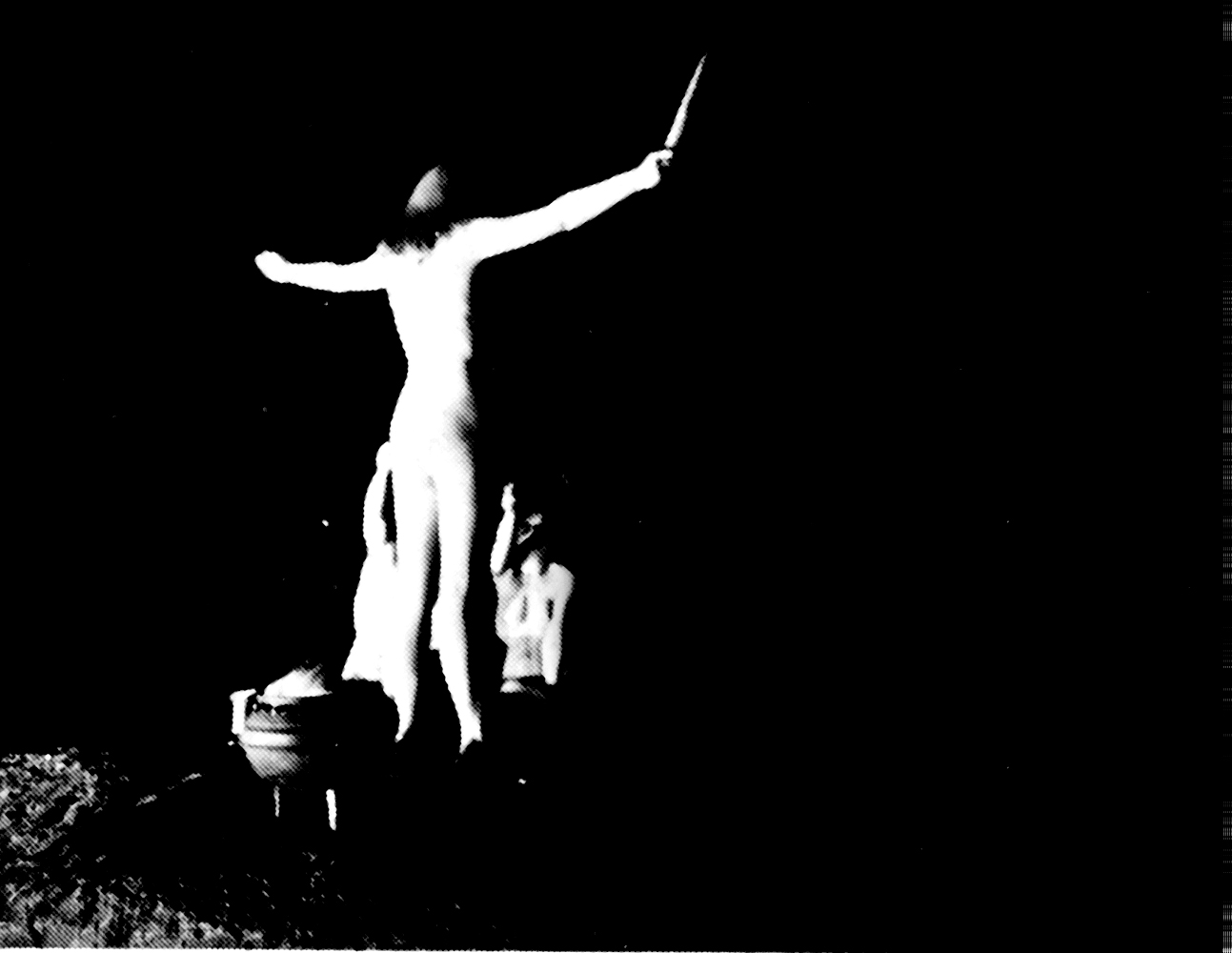

In the 1920s, two very different histories of witchcraft appeared: the 1922 Danish film Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages, and the Reverend Montague Summers’s History of Witchcraft and Demonology, published in England in 1926. Both were instant sensations and instantly controversial. Benjamin Christensen’s film, which included nudity and scenes of torture, was a scathing critique of Catholicism, arguing that those accused of witchcraft had perhaps been sufferers of “modern” diseases like hysteria and kleptomania. On its release the film caused riots: By one account, 8000 Catholic women stormed the streets of Paris in protest, incensed that modern Catholicism be compared to a barbaric episode of its past that it had largely forgotten.

Summers, on the other hand, neither criticized nor apologized for Christianity’s persecution of witches—he embraced it. He believed that the church was infallible and that men and women were capable of knowingly giving themselves to Satan: “There has invariably been an open avowal of intentional evil-doing on the part of the devotees of the witch-cult,” he wrote with fervent orthodoxy. Critics found the book compulsively readable, but were aghast at Summers’s argument that the Catholic Church had been just and right in trying and executing untold thousands of witches. In Summers’s mind, the church had been if anything too lenient: “The Church dealt very gently with the rebel and the heretic, whom she might have executed wholesale with the greatest ease.”

***

The early 20th century saw a renewed interest in the history of witchcraft, after years of neglect and denial by historians who preferred not to engage with such a disgraceful episode. In many ways, the Reverend Montague Summers was the perfect avatar for this resurgence. A cartoonish figure with a broad, moon-shaped face, a black shovel hat, and a flowing cape, he seemed to come from some other era. He had a high-pitched voice and a strange chuckle; friends and colleagues wondered if he was, in fact, in league with the devil, or had participated in a Black Mass; one family who moved into a residence previously owned by Summers complained that he’d left it haunted and went so far as to perform an exorcism.

Born in 1880, son of a banker and the youngest of seven children, Summers grew up surrounded by the well-educated and the literary. He was educated at Trinity College, Oxford, and in 1907, shortly after he graduated with honors, he published a “distinctly decadent book of verse,” Antinous and Other Poems. The poetry featured sexual innuendo buried beneath layers of Roman and Greek mythological allusions. One reviewer labeled it “the nadir of corrupt and corrupting literature”; friends noted that any corrupting influence was somewhat mitigated by its obtuse tone and low quality. The book faded into obscurity.

Summers’s early life was marked by an oscillation between two opposing poles: an appetite for controversy and taboo at one end, and for religious orthodoxy at the other. In 1908, he abruptly entered the seminary: That year he was ordained as an Anglican deacon, first in Bath, then in the Bristol suburb of Bitton, where he spent his days studying Satanism. It was during this time that he became convinced that his church was haunted, exhibiting, according to one friend, “a morbid fascination with evil which, even if partly a pose, was shocking in a clergyman.”

His life as an Anglican deacon was short-lived, however, and he left pursued not by ghosts or devils, but by accusations of homosexuality. In 1910 Summers and another clergyman were accused of pederasty, and though they were ultimately acquitted of the charges, Summers quickly left both Bristol and the faith. Within a few years, he had converted to Catholicism. In later years Summers would claim that he’d been ordained as a priest and wear corresponding vestments, but there is no record of the ordainment.

Summers never headed a parish, nor did he enter a religious order. In lieu of a religious occupation, he turned back to writing, and in the years after the war he became known as a scholar of Restoration Theater. A few years later, he was contacted by publisher C. K. Ogden, who was at the time editing a multivolume history of civilization. Ogden had been hoping Summers would offer something about English drama, but Summers responded instead with a proposal for a study of witchcraft.

***

Summers ultimately produced two separate books: The History of Witchcraft and Demonology and, a year later, a companion volume, The Geography of Witchcraft. In them he presented testimonies, trials, verdicts, confessions, and other primary documents describing the witch persecutions of the Middle Ages—many of them appearing for the first time in English.

The primary documents accounted for much of the History’s success. For too long, even serious historians had tended to gloss over this tragic aspect of Europe’s maturation, treating it as an aberration best ignored. Summers recognized that witch trials were at the very heart of European history, and that a “history of civilization” such as Ogden had envisioned required not just its triumphs, but also its horrors. History, Summers saw, consists not only in what is done by great men but also what is done by midlevel bureaucrats and illiterate midwives.

Perhaps the best example of this was the trial of the servant girl Gellis Duncan in Scotland in 1590. As Summers relays, Duncan’s employer became suspicious when he discovered her sneaking out at night, and in short order she was accused of witchcraft, tried, and tortured. During her torture, she confessed and implicated half a dozen other individuals, many of whom in turn were tortured into confession and then executed.

What is noteworthy about Duncan’s trial is that news of it soon found its way to the King of Scotland, soon to be king of England, James I. James was terrified of political assassination by witchcraft, and, having recently sailed through a storm that he was sure had been engineered by magic, he took an active interest in the trials surrounding Duncan, going so far as to personally interview one of the accused, a midwife named Agnes Sampson. James’s fear wasn’t entirely paranoia; real plots were afoot, including one concocted by his cousin Francis Stewart, who himself blurred the line between the real and imaginary threat, employing curses and wax dolls as well as swords and armies.

In laying the occult alongside the political, Summers’s account of these events helps to remind us that history—even royal history—doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and that even a local witch trial of a poor servant girl can reverberate throughout a kingdom. His contemporary readers were reminded that for centuries the witch persecutions had been central to Europe’s cultural and economic landscape.

But the book was singular for another reason: Summers believed with every fiber of his being that witchcraft was real. “Faith, the Bible, actual experience,” he writes in A History, “all taught that witchcraft had existed and existed still. There could be and there is no sort of doubt concerning this.” Summers found support for his conviction in the views of the great men of history, from popes to scholars. He also argued strenuously for the power and efficacy of bureaucracy itself. His book’s strength, he contended, lay in its demonstration “by a number of citations how in the past this enormous wickedness had been impartially investigated, had been argued, and proven by the keenest minds of the centuries.”

Deluded as to the nature of evil, he was similarly deluded as to the nature of his own success, which he took as proof of the correctness of his attitude. The History was popular, he explained, because it alerted people “to the danger still energizing and active in their midst”: “The evil which many had hardly suspected, deeming it either a mere historical question, long dead and gone, of no interest save to the antiquarian, or else altogether fabled, was shown to be very much alive, potent in politics, potent in society, corrupting the arts, a festering, leprous disease and decay.”

Summers believed in the power of the written word and in the historical record. His work is the 20th century’s last gasp of a sort of history that refused to recognize the evolution of human character, morality, and thought. His rhetoric at times struggles to accommodate modern psychology (“It is not denied that in some cases hallucination and self-deception played a large part”), but repeatedly falls back on the infallibility of the church (“such examples are comparatively few in number, and these, moreover, were carefully investigated and most frequently recognized by the judges and divines”), and his own surprisingly anachronistic views (“The silly body, the blind, the dumb, the idiot, were, as often as not, afflicted by demons; the raving maniac was assuredly possessed”).

For all its fidelity to history, Summers’s work is a confrontation with the various elements of modern life he’d come to detest. He had, as one reviewer later noted, “a flatteringly poor opinion of anthropologists,” and he saw anarchists and Communists (groups he regularly conflated) as direct descendents from the witches of the Medieval world. Witches were “avowed enemies of law and order, red-hot anarchists who would stop at nothing to gain their ends.” When his patron, Lady Cunard, introduced him to her husband, Lord Balfour—who expressed disbelief in the existence of people who craved evil for evil’s sake—Summers produced a political analogy: “Well, Lord Balfour, you have only to think of the views of some of your opponents.” Liberals, socialists, and anarchists, he told Balfour, all bore “the witch philosophy.”

Scholars and critics immediately attacked him for this kind of hysteria. Theodore Hornberger disparaged Summers’s “alarmist themes”: “It is just about time, thinks Mr. Summers, for legislation, a bit more severe, if possible, than the famous statute of James I. The political implications of this logic are indeed alarming, but perhaps not always with the effect intended by the author.” In a similarly scathing review, H. G. Wells noted that Summers “hates witches as soundly and sincerely as the British county families hate the ‘Reds.’” Wells, anticipating Shirley Jackson’s story “The Lottery,” saw in Summers’s work a “standing need” of mankind “for somebody to tar, feather, and burn. Perhaps if there was no devil, men would have to invent one. In a more perfect world we may have to draw lots to find who shall be the witch or the ‘Red,’ or the heretic or the nigger, in order that one may suffer for the people.”

Other reviewers castigated Summers for not “judging between different kinds of evidence,” and for his “odd mixture of learning and almost childish credulity.” But Summers maintained that a religion cannot on the one hand assert an unbroken line of pious infallibility, while, on the other, offer the kind of apologetic backtracking that characterized 20th century Church thought. The 1914 entry on witchcraft in the Catholic Encyclopedia (written by Herbert Thurston), attempting to thread the needle between the church’s past and its future, is reduced to equivocations: “In the face of Holy Scripture and the teaching of the Fathers and theologians the abstract possibility of a pact with the Devil and of a diabolical interference in human affairs can hardly be denied, but no one can read the literature of the subject without realizing the awful cruelties to which this belief and without being convinced that in 99 cases out of 100 the allegations rest upon nothing better than pure delusion.”

Summers’s attitude was vile, perhaps indefensible, but at least it was consistent. As the Church lumbered towards Vatican II, it found itself caught between the demands of a tradition and a need for modernization. Despite what apologists like Thurston might have you believe, exorcism was then (and is still today) a sacrament; Summers’s work brought this history out of the Latin and into the light.

***

In the 80 years since its release, Häxan has entered the annals of film history, a major milestone that remains celebrated despite (or perhaps because of) its salubrious content and suspect diagnoses. As a history of witchcraft it is dubious, but as a cinematic experience it remains arresting. Something similar can be said of Summers’s work: Taken as history, it is flawed at best—yet his books on witchcraft remain milestones in their own right, and continue to offer a compelling (if unsettling) reading experience.

And yet the years have not been kind to either Summers or his work. After The History’s popular success and critical dismissal, Summers continued to present himself as a serious scholar, producing in 1928 the first English translation of the Malleus Malefaricum (“The Hammer of Witches,” the notorious medieval manual for investigating and trying witches), but as he delved further into the supernatural—churning out books on vampires, ghosts, and werewolves—his work became increasingly sensational and marred by increasingly sloppy scholarship. Gradually he faded into obscurity, and, horrified by the savageries of World War II—the Blitz, the atrocities in mainland Europe, Hiroshima, Nagasaki—he retreated to the English countryside and died in 1948.

Just as historians for decades tried to ignore the history of witchcraft, preferring to minimize the impact of such a blight on Europe’s cultural history, historians these days have preferred to downplay Summers himself. Because he was never a formally trained scholar, it was easy for academic historians to write him out of the historiography of witchcraft—even though his translation of the Malleus Malefaricum remained the only English edition until 2006.

By necessity a figure of contradiction, he managed to be, according to one friend, “both near-blasphemous and obscene in his conversation” while at the same time being “a genuine believer, with a sincere desire to serve the Church.” The strange triumph of his writing on witchcraft writings is in their synthesis of the two halves of his personality, the devout and the unconventional. These impulses had once been distinctly at odds, but as the landscape around him changed, and modern culture began to abandon the church, being as religious as he was became itself irregular. Emphatically ill-fitted for the 20th century, Summers was yet its inevitable by-product: an unstable atom spun loose by cultural fission.