The Listserve brings online strangers together in an era oversaturated with friends

"Like all the men of Babylon," wrote Jorge Luis Borges in The Lottery of Babylon, "I have been preconsul; like all, I have been a slave." The story details a society ruled by a mandatory game of chance which metes out power–and punishment–through the vagaries of chance. One may, by the lottery's eldritch hand, be declared invisible for a calendar year, find one's enemies imprisoned, or be forced to execute a friend. The system is designed to infuse chaos into the cosmos, oftentimes without conceivable purpose.

The Lottery of Babylon began innocently enough. It was a game, created by venal merchants, played by commoners, and its rules were simple: tempt fate, win silver coins. But as it evolved, it took on moral dimensions, dark corners, and ecclesiastical force. Although it will take a few billion more adherents to even begin chasing this mystical essence, we have a Lottery of Babylon among us today. It's called the Listserve.

The Listserve is a mailing list lottery. Sign up for the Listserve, and you're joining a massive e-mail list. Every day, one person from the list is randomly selected to write one e-mail to everyone else. That's it. As of this writing, the Listserve has 21,399 subscribers. There has been one email per day since April 16th, 2012. Run by a group of Masters Candidates in NYU's Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP), the Listserve emerged from a class exploring new ways of creating conversational spaces online. There were other ideas: chain letters, or a message board for only 100 people at a time. But eventually email's directness and ease-of-use won out. An email flies straight, circumventing the myriad distractions of other online gatherings, where some voices pack disproportionate clout (or, er, Klout).

On Twitter, for example, politicians and celebrities with millions of followers can dominate the conversation with a single post. Listserve co-founder Alvin Chang compares this centralization of communication on the web to an ancient rock, the Acta Diurna: a megalithic stone in the middle of the Roman Forum etched with military announcements and notable deaths. It was the first daily news digest in recorded history, and it belonged to Caesar. In the Twitter age, the Kim Kardashians and the Justin Beibers wield the tablets viewed by millions. "No matter how loud your voice," explains Chang, "you're still in the Roman Forum with millions of other voices."

But the Listerve community is all potential energy. It's conjured into existence with each email, once a day, usually in the morning. What people do with their brief stint of power is as random as the lottery itself. The Listserve has existed for a little over a year, and although I've been a subscriber for only a fraction of that time, my inbox has received short stories, epigrammatic koans, and peace treaties. It tends to skew towards personal stories and experiments; some people shout into the group and wait to hear the echoes resonate back to them. Once, someone sent in a Bloody Mary recipe from South Sudan. A successful Listserve email tends to generate hundreds of responses–an instant community for the winner.

In a social media landscape dominated by forced symmetry with real-life identity, family, and workplace (and all the attendant paranoia about privacy and control) the Listserve is beyond refreshing. Like a good friend, it asks little of you: only that you listen, because everyone has the right to speak. "The Listserve isn't about points," another Listserve co-founder, Greg Dorsainville, explains, "or likes, or favorites, or +1, or instant fame. It's about trying to connect with new people, using a medium as simple as words."

The community engendered by the Listserve feels like a vestige from an earlier web--those decades of mailing lists, chain letters, and perpetually reinvented forms of community. It feels archaic to be greeted each day by the thoughts of a total stranger. If I ever win the lottery, I genuinely have no idea what I'd say. How often do you get a chance to speak to 20,000 strangers at once? Surprisingly, none of the emails I've received have harnessed the platform to advertise brands, wares, or projects. No one on Listserve has buzz-marketed; somehow, an unspoken agreement has been reached about this. It's as though the lottery, like its Borgesian antecedent, were sacred.

Where Facebook has devalued the word "friend" to the point of worthlessness, Listserve takes the opposite tack: it has imbued "stranger," with its associations of danger and otherness, with an immediacy much more akin to real friendship. Listservers don't spam you with vacation photos or cheap pleas for attention. Instead, they share long, personal stories of adversity and dole out big-picture life advice. "With the lottery mechanism slowing down interaction," says Dorsainville, "the emails have a pleasant tone: people talk about their own lives, and how they have battled against hardship or achieved success in their life. People share slices of their own identities and what have shaped them."

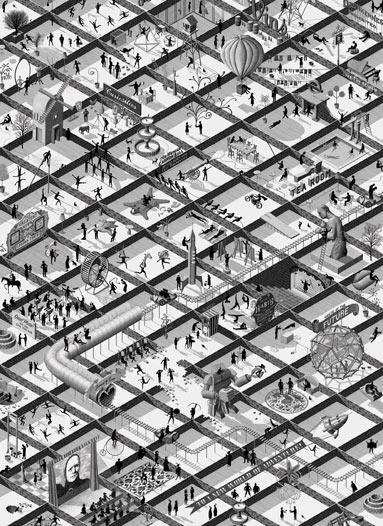

The Listserve is built like a democratic Acta Diurna, a centralized message-board passed from person to person each day, without consideration of status, or message. Its powder-keg of competing voices have all vowed to hush up and listen in exchange for an equal shot at this soapbox. In this way, the Roman Forum isn't conquered, it's shared; in Chang's estimation, it's no longer the Forum at all–"it's the Great Lawn at Central Park, where you lay back and watch the people."

Which isn't to say Listserve doesn't also employ the mechanics of its medium. The web's addictive quality stems, in part, from its randomness. At any moment, I could receive an email which would tickle and surprise me. I have found the course of my life altered by a single message: a job opportunity, a divulgence of love, bad news. By isolating this alchemy and guaranteeing that it will happen daily, the Listserve allows its users to loosen their death-grip on the refresh button.

The best emails, says Alvin Chang, are "the ones where the writer makes themselves vulnerable, and the community rewards them for it." This takes many forms, but Greg Dorsainville reminisces fondly about how one winner boldly called for a picnic, which resulted in a beautiful day in Prospect Park, "eating pie, singing little mermaid songs, and meeting new people."

"We should do that again," he says.

It's not always picnics and mermaid songs, and not everyone's advice is worth taking. But at its best, the Listserve offers a glimpse into an alternate universe, a place where the Internet moves quietly, and where resonances between strangers, discovered through risk and vulnerability, are cherished like the lottery-winnings they are.