Certain places will always impose their own particular empire on their surroundings, sport their immemorial insignia in the middle of a park just as they would have done far from any human intervention. -- Marcel Proust, Swann's Way

Field daisies jutting up between a sidewalk crack, rhododendrons bedecked with fuchsia blooms, buttercups nodding in the breeze — somehow they all seem more charming, more magical, when discovered growing in the city. New York's many urban naturalists would likely agree with this observation. A few months ago, writer Caleb Crain posted a photograph of a wildflower he plucked as part of his ongoing quest to identify blooms in his Brooklyn neighborhood. "Braved dog pee and allergies to scan for you," he wrote on his blog, Steamboats Are Ruining Everything. "Identifications welcome." Someone took up the challenge. "Hardy Geranium," a commenter offered. It joined spiderwort, white snakeroot, daisy fleabane, and even an interloper from the Keystone State, the Pennsylvania smartweed.

Searching for wildflowers in the boroughs isn't new. The hobby was championed toward the end of the 19th century by William Hamilton Gibson, a popular illustrator, naturalist, entomologist, photographer and man of letters. For nearly 20 years Gibson reigned as the sage of Brooklyn

A stroke brought on by overwork carried off Gibson in 1896, ending the career of a man so highly regarded that, like a saint, his passing inspired mythologizing

I discovered both Gibson and a love of urban naturalism a couple summers ago while residing in Providence, Rhode Island. I had been living in a poky two-bedroom apartment above a liquor store. My living-room window looked into the living-room window of the building opposite, and my bedroom window looked, well, into the bedroom window of the building next door. My first month in Providence, city workers came and planted a small maple. It delighted me and offered me a modicum of privacy. If the light was just right, I could almost imagine that I inhabited a bosky little burg. The late-afternoon sun, striking the maple's leaves, would stipple the pergamon flooring of my place with wavering blade-like shadows. The effect made even the air seem different — clean, refreshing, slightly tangy from its trip over Narragansett Bay. A month later, city workers returned to repair my street's water main. Not a week later, the young maple was dead.

The month I spent contemplating that ill-fated sapling inspired me to search out nature beyond my neighborhood. Without a car, I contented myself with the few parks on Providence's east side. I didn't bother collecting wildflowers or watching birds, two of the more popular nature hobbies. I instead took up mushroom hunting. Perhaps a strange choice on my part, considering that 20 years earlier, when my family and I lived in Vienna, my mother suffered a mushroom poisoning and had barely survived it; a false parasol had somehow slipped in with some harmless boletes and, browned with bacon and served with potatoes, made it onto her dinner plate.

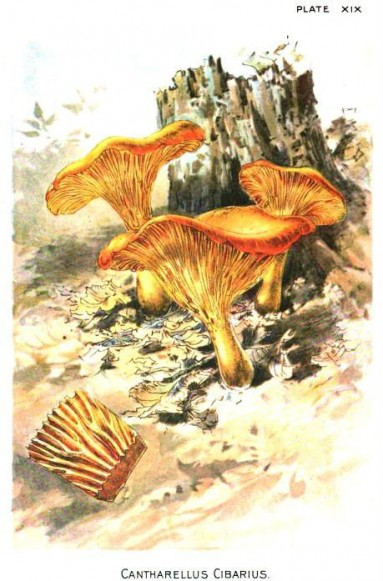

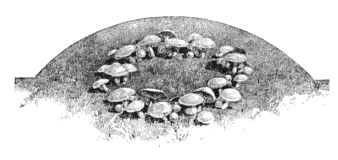

Nonetheless I threw myself into my new pastime, trying to keep memories of her abed in an Austrian Krankenhaus, pale, wan, her liver and stomach ravaged, out of my head in the process. Each evening, a wicker basket in one hand and a cheese knife in the other, I set off to explore Providence's wilds. I stalked the city's parks and greenways, not expecting to find much. As it turned out, Providence surprised me by proving a veritable mycological paradise. It rewarded my first few forays with basketfuls of porcinis. A small park notorious for vice concealed more than drug deals and sex: legions of black trumpets directed their mute fanfare at the treetops. But the real payoff came when my wanderings led me down some decommissioned railroad tracks, and I discovered clinging to an embankment a flush of golden chanterelles. They appeared in such profusion as to dazzle me. I began to snatch them up, only vaguely concerned that I'd get them all in my basket. I took only the choicest ones, leaving the others in order to preserve their delicate mycelium web. That evening I dined in grand style on whole-wheat pasta and mushrooms that at the market would have cost $14 a pound.

It didn't take long for me to realize that Providence contained nearly as many varieties of mushroom as it did of people. Soccer fields teemed with puffballs and saffron milk caps huddled around swingsets. More than once I trespassed onto manicured lawns to cut a chicken of the woods from the oak it grew on or to collect a few russulas. Even the most litter-strewn brownfield surrendered unexpected fungal bounty. A city I had once thought so dull, so devoid of nature, became for me, in appropriately Gibsonian fashion, a garden of earthly delights.

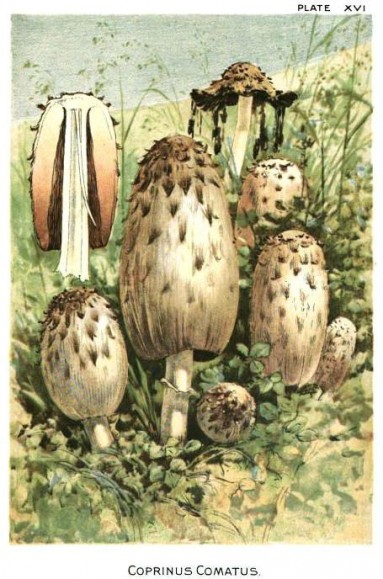

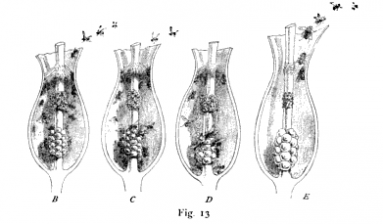

Mushrooming requires a great deal of knowledge and discernment. I dedicated myself to properly researching my new hobby, spending weeks memorizing spore prints and gill structures. In the stacks of Brown University's Rockefeller Library I found a copy of Gibson's Our Edible Toadstools and Mushrooms and How to Distinguish Them (1895). At first glance it looked much like other field guides from that era, yellowing, its illustrations fading. Upon closer inspection I saw that it possessed virtues uniquely its own.

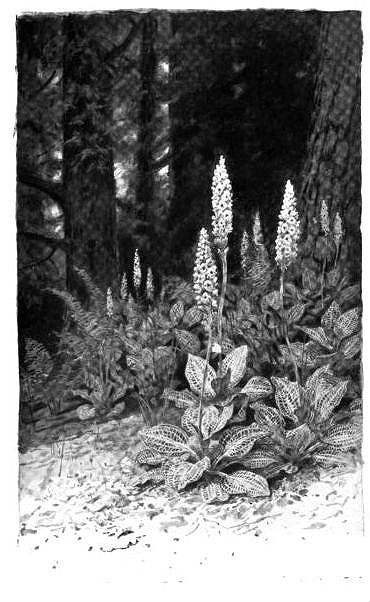

The book commands admiration purely for its visual appeal. The pictures have a certain whimsy that distinguishes them from the drily scientific. The frontispiece greets the reader with a sketch of "The Deadly 'Amanita,'" with a ghostly image of a skull superimposed on its universal veil. The overleaf features a dedication inscribed within the signature hourglass contours of this same mushroom. "Forewarned is forearmed," it reads. A web of fine myceli enmesh the introduction. The first page of each chapter features tendrils and flowers, and the color plates present realistic renderings of apricot-colored chanterelles and coal-black death trumpets. Yet the discussion of its subject offers enough informative detail to allow even the novice amateur mycologist to forage with peace of mind. I confess I felt tempted to bring that volume into the field with me, but with its loose pages, worn spine and tattered covers, I knew it would have never survived the trip.

I nearly met my own end when I mistook the toxic Boletus sensibilis for its harmless lookalike, Boletus bicolor. (Age-old wisdom has it that every edible mushroom has a poisonous twin.) An uncomfortable week spent recovering didn't discourage me.

Urban foraging on Indian summer days chased away my blues. It also made me something of a curiosity. Strangers often approached me as I hunched under a pine or cleared leaf litter from beneath a bush to learn what I was up to. When I told them I hunted mushrooms, they typically responded with something along the lines of "Do you have a death wish?" But I left almost everyone I met with a new impression of the humble fungi they had hitherto trampled under foot or shredded with their lawnmovers. Such marvelous — and harmless! — delicacies they never thought could spring from their city's soil. Older Russian women would occasionally ask to see my harvest. They cooed when I showed them what I had found, and they would launch into stories about their own adventures mushrooming in the forests outside of Moscow or the graveyards of Vladivostok. The closer mushrooms grew to the dead, they claimed, the firmer their fruiting bodies.

***

Like my mushrooming adventure, William Hamilton Gibson's tale began in New England. Hailing from a long line of stalwart Yankees, including Washington Aliston, a renowned Unitarian minister, and the painter and poet Ellery Channing, Hamilton displayed from childhood keen interest in the natural world. He often wandered the fields and forests outside his family's home in Newton, Connecticut, in search of flowers and insects to sketch. Later he would write that his "love for the insect and passion for the pencil strove hard for the ascendancy and were only reconciled by a combination which filled my sketch book with studies of insect life."

Like my mushrooming adventure, William Hamilton Gibson's tale began in New England. Hailing from a long line of stalwart Yankees, including Washington Aliston, a renowned Unitarian minister, and the painter and poet Ellery Channing, Hamilton displayed from childhood keen interest in the natural world. He often wandered the fields and forests outside his family's home in Newton, Connecticut, in search of flowers and insects to sketch. Later he would write that his "love for the insect and passion for the pencil strove hard for the ascendancy and were only reconciled by a combination which filled my sketch book with studies of insect life."

The dim view his elders took of his habit likely shaped his determination. A grammar-school teacher of his assessed Gibson as slow-witted and characterized by a "tendency to take on fat." Only his mother understood his capacities. She alone indulged him in his pursuits. Part of her bureau she permitted to serve as a caterpillar nursery ("the worm drawer," she called it), and during school hours she would dutifully care for his many other creepy-crawly specimens.

Gibson labored vigorously to hone his talents. While visiting Brooklyn as a teenager a display of wax flowers in a friend's home captivated him. Upon learning the name of the craftsman responsible for the likenesses Gibson contacted him to see if he would take him on as an apprentice. The craftsman agreed. A quick study, Gibson soon surpassed his master in skill. Once he fashioned a bouquet so convincingly realistic that the lady friend to whom he had presented it pressed it to her nose and, before she could realize her mistake, crushed his creation.

A volatile economy stymied Gibson's creative ambitions. Five years before the bank failures that touched off the Depression of 1873, his father, a Wall Street broker, died, leaving behind bad investments that bankrupted his family. The blow forced an 18-year-old Gibson to abandon his studies at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute for a position at the Brooklyn Home Life Insurance Company.

The dull world of indemnities and actuarials chafed against Gibson's artistic temperament. One afternoon while making the rounds to solicit business, Gibson arrived at the home of a draftsman. He went through the motions of attempting to sell the draftsman a policy. When the draftsman declined, Gibson, who had noticed a few of the draftsman's drawings, asked if he might stay the afternoon to watch him work. The draftsman agreed, and the hours Gibson spent in his company proved transformative. Believing his own skills equal to those of the draftsman, he resolved that day to "do such work has he," as he later wrote to a friend. He abandoned his clerkship for drawing, much to the annoyance of his family and friends, and what money he had he spent on materials. He worked 16 to 17 hours a day to master the art of drafting. Those closest to him feared for his well-being. "Will ... will always be busy day and night until he breaks down in health," Gibson's wife complained in a letter to his mother. "I think that would be the only thing (except, perhaps, a fortune) which would put a stop to his midnight work."

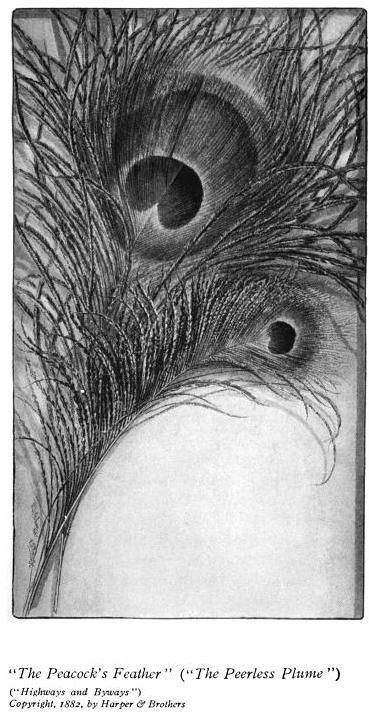

Fortunately, Gibson's efforts paid off in rather short order. In 1878, Harper Brothers asked Gibson to illustrate a short article by Helen S. Conant entitled "Birds and Plumage" with 16 drawings for Harper's Magazine. His lead illustration, that of a single peacock's feather, caused a sensation among readers and critics, who hailed it a monumental achievement. Its grace and verisimilitude carried a poetic charm, they claimed. Gibson had captured the warp and weft of a bewildering multiplicity of strands. Celebrated art history professor Charles Eliot Norton opined that Gibson's feather "ought to be as well known as Rembrandt's shell, or Hollar's furs." Indeed, never before had Harper's featured so accomplished an illustration — and for good reason: Never had the magazine spent as much to reproduce an illustration as it had for Gibson's.

The peacock feather made Gibson's career. A little more than two years after happening upon the draftsman, the celebrated young illustrator found his skills in high demand. As versatile as he was talented, he excelled in watercolor, pencil, and charcoal. He began producing drawings in rapid succession, each as remarkable as the one preceding it. The London Times declared that his work displayed "a rare gift of feeling for the exquisitely graceful forms of plant life and the fine touch of the expert draughtsman." Not content to rest on his laurels, Gibson took up the pen along with the brush. His first major written work was Pastoral Days (1882), a collection of articles he had previously published with original renderings in Harper's Magazine. Deemed by critics a prodigy of nature illustration through woodcut, Pastoral Days also cemented Gibson's literary status as "a Thoreau who had read both Darwin and Ruskin," according to the London Academy. The Saturday Review wished "to hear more from him soon."

Gibson's ascendant star attracted other literary luminaries. In 1886, Gibson worked with Rebecca Harding Davis on Southern Sketches, a book on life and nature in Dixie. For two months he traveled through Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana, and took more than 500 photographs of the sights he encountered on his journey. Yet as pleasant as he found the South generally, Southern cuisine left him wanting. The dishes of the region repulsed him. "A beautiful country and full of interest, if, forsooth, one might exist without a stomach," he complained in a letter to his wife. "Everything here, even a boiled egg, is taught to swim in hot fat, and is only rescued therefrom by the famished boarder, who sometimes is obliged to bolt it after scraping off the congealed lard."

***

Occasional foreign or domestic trips notwithstanding, Gibson spent most of his time in his Brooklyn home, working at his drafting table and only rarely finding occasion to visit his country house in Connecticut. For artistic inspiration, he depended on the city's greenswards. Local naturalism informed much of his later work, which he devoted to instructing urbanites in the finer points of discovering wilderness among the brownstones. Behind this purpose lay Gibson's understanding that the majority of his readers had to content themselves with city parks and, if they were lucky, small plots.

Occasional foreign or domestic trips notwithstanding, Gibson spent most of his time in his Brooklyn home, working at his drafting table and only rarely finding occasion to visit his country house in Connecticut. For artistic inspiration, he depended on the city's greenswards. Local naturalism informed much of his later work, which he devoted to instructing urbanites in the finer points of discovering wilderness among the brownstones. Behind this purpose lay Gibson's understanding that the majority of his readers had to content themselves with city parks and, if they were lucky, small plots.

In "Backyard Studies," published in 1886, Gibson articulated his conviction that city backyards could become "a means of grace." That October he received a letter from a friend who complained she could no longer study wildflowers since she moved to New York. Such delights she supposed did not grow in the city. Intent on dispelling this impression, Gibson encouraged her to explore her backyard, where she could learn for herself her mistake. Shortly after this exchange he visited her and discovered, in a plot no bigger than 25-by-12 feet, some 64 varieties of wildflower, including three kinds of goldenrod. Even the most forlorn nature lover could not deny this bounty right at her feet. These "graceful varieties of the woodside and the hay-field," Gibson wrote, could "serve to reawaken and console the latent yearning of our unfortunate metropolitan exile."

Gibson assuaged his own yearnings in a "deserted corner" of Prospect Park. "Innocent of the gardener," as he described it, this wild nook made him feel he "might as well be in the Berkshires" whenever he visited it. He noticed that it harbored birds that lived nowhere else in the city: scarlet tanagers, rose-breasted grosbeaks, red-eyed vireos, and many others. He sketched the rare plants — blood roots, cranesbills, and Jack-in-the-pulpits — that grew among the park's thickets of oak and white birch and for hours sat with other Brooklyn artists to admire its tangle of acanthus bushes. No other area of the park, Gibson believed, resembled so faithfully the larger wildernesses outside the city.

The spring of 1887, however, saw Gibson's bower imperiled when the Brooklyn Parks Commission decided to tame this last piece of urban wilderness. It ordered dozens of trees chopped down and the undergrowth cleared. When work began on this project, Gibson sounded the alarm in a series of letters to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. "One of the wildest and most beautiful sections of the Park has been invaded by the butcherly Goths and Vandals known as our Parks Commissioners," he wrote. His favorite nook stood a mess of "bleeding stumps" and a "wreckage of timber among the various bonfires." He identified for readers the commission's killing field: a copse of white birch, black birch, hornbeams and willows, poplars, dogwoods, chestnuts, nettle trees, elms, sweet gum, and maple alders. The Parks Commission denied Gibson's charges, claiming they intended only to clear out invasive species. The forest trees, they insisted, had gone unmolested. Gibson remained unconvinced. "It is not of the slightest consequence to anybody what your scribe considers a forest tree," he returned. "The nature students and authorities settle that."

Gibson asked city officials to assemble a committee of "the most honored and distinguished citizens of Brooklyn" to assess the situation in Prospect Park and to offer its opinion. After surveying the damage, the committee affirmed that Gibson had indeed been correct in his allegations. Their argument lost, the Parks Commission shifted tactics; the commissioner maintained that "improving the park" had been his intent. Offended by this defense, Gibson sought to settle the matter once and for all by inviting the Central Park Comissioner, Samuel Parsons, to weigh in on the controversy. After examining the evidence, he sided with Gibson. The Brooklyn Parks Commission fell under tremendous public pressure to cease its improvements, and so cease it did, leaving Prospect Park free to return to its original state.

With so many of us packed into metropolitan areas, the wild spaces beyond the city's limits threaten to fade from memory, even as we look to them to fuel our ever-expanding economies — wild spaces that, as Edward Abbey writes, are "more our home than the little stucco boxes, wallboard apartments, plywood trailerhouses, and cinderblock condominiums in which the majority are now confined by the poverty of an overcrowded industrial culture." Only in field lot and park do we find intimations of these larger wildernesses beyond the city, beyond suburbia, beyond the last Costco or factory outlet mall. In forgetting the first, we forget the second. And in forgetting the second, we might forget the biggest ecological challenges facing us — climate change, deforestation, mass extinction. Most schoolchildren cannot identify a viceroy butterfly from a monarch, or a blackberry from a mulberry. Rather than deplore this fact, we ought to grab a field guide and walking stick and set out to re-discover our cities so that we might remember no matter how we might manage to banish or obscure her, Mother Nature abides.

Gibson would have liked to have seen all of Brooklyn return to the wild. He exhorted his readers to "seed the whole community with thistles [and] run the gauntlet of the city ordinances." Many heeded his call. Backyard plots teemed with wildflowers, and hundreds flocked to Gibson's public lectures, which, because he enjoyed them, he gave frequently. (In 1894 alone he lectured 64 times.) He likened himself to a missionary who looked forward to a time when "a man may read a botanical work without understanding Latin."

Perhaps to hasten this world to come, he wrote books almost anyone could understand. His oeuvre covers everything from meditations on country life to more whimsical topics. His Strolls by Starlight and Sunshine (1890), for instance, summons readers to moonlit idylls. "We have explored a new world," he writes, "a realm which we can look in the face on the morrow, with an exchange of recognition impossible yesterday." Much like a certain poet from the borough, Brooklyn backyards contain multitudes.