Writing about a disease suffered almost exclusively by women presents the disordering question of form.

In 1972, Susan Sontag made notes in her journal for a work to be called “On Woman Dying” or “Deaths of Women” or “How Women Die.” Under the word “material” she listed 11 deaths, including the death of Virginia Woolf, the death of Marie Curie, the death of Jeanne d’Arc, the death of Rosa Luxemburg, and the death of Alice James. Alice James died of breast cancer in 1892, at the age of 42. In her own journals, James describes her breast tumor as “this unholy granite substance in my breast.” Sontag quotes this description in Illness as Metaphor, the work she wrote after undergoing treatment for breast cancer.

Sontag is diagnosed with breast cancer in 1974, at the age of 41, but Illness as Metaphor is cancer as nothing personal. Sontag rarely writes “I” and “cancer” in the same sentence. As she explained in Aids and Its Metaphors, “I didn’t think it would be useful—and I wanted to be useful—to tell yet one more story in the first person of how someone learned that she or he had cancer, wept, struggled, was comforted, suffered, took courage … though mine was also that story.” Rachel Carson was at work on Silent Spring when she was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1960, at the age of 53. Like Sontag, Carson wrote one of the most significant books in the cultural history of cancer, but Carson won’t admit the link between herself and the disease she dies of in 1964.

Sontag’s journal entries during cancer treatment are notable for how few there are that mention her cancer and how little they say. The little they do say illustrates breast cancer’s cost to thinking, a price paid most dramatically during chemotherapy—Sontag was in chemo for two and a half years—which can have severe and long-lasting cognitive effects. In February 1976, while undergoing treatment, Sontag writes “I need a mental gym.” The next entry is months later, in June 1976: “when I can write letters, then …”

In Jacqueline Susann’s novel Valley of the Dolls, one character, Jennifer, suicides by overdose after a breast cancer diagnosis. “All my life,” Jennifer says, “the word cancer meant death, terror, something so horrible I’d cringe. And now I have it. And the funny part is, I’m not the least bit frightened of the cancer itself—even if it turns out to be a death sentence. It’s just what it’ll do to my life.” The feminist writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, diagnosed with breast cancer in 1932, kills herself too: “I have preferred chloroform to cancer.” Susann, diagnosed at 44, dies of breast cancer in 1974, the year Sontag is diagnosed.

The poet Audre Lorde is also diagnosed at the age of 44, in 1978. Unlike Sontag, Lorde uses the words “I” and “cancer” together, and does so famously in The Cancer Journals, which includes both an account of her diagnosis and treatment and a feminist call to arms: “I don’t want this to be a record of grieving only. I don’t want this to be a record of tears.” For Lorde, the crisis of breast cancer meant “the warrior’s painstaking examination of yet another weapon.” She dies of breast cancer in 1992.

Like Lorde, the novelist Fanny Burney, who discovers her breast cancer in 1810, writes a first-person account of her own mastectomy. Her surgery, though—rare at the time—is done without anesthetic, and she is conscious for its duration: “...not for days, not for Weeks, but for Months I could not speak of this terrible business without nearly again going through it! I could not think of it with impunity! I was sick, I was disordered by a single question—even now, nine months after it is over, I have a headache from going on with the account! and this miserable account which I began 3 Months ago, at least, I dare not revise, nor read, the recollection is still so painful.”

“Write aphoristically” Sontag notes in her journal when considering how to write about cancer in Illness as Metaphor. Breast cancer exists uneasily with the “I” (almost always a woman’s) that might “speak of this terrible business”—the “I” often appearing in excess, or not at all. It is an “I” sometimes annihilated by cancer, but sometimes pre-emptively annihilated by who it represents, either by suicide or by an authorial stubbornness that does not permit “I” and “cancer” to be joined in one unit of thought:

“[Redacted] is diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of 41.”

or

“I am diagnosed with [redacted] in 2014, at the age of 41.”

The novelist Kathy Acker is diagnosed with breast cancer in 1996, at the age of 49. “I am going to tell this story as I know it,” begins the uncharacteristically straightforward piece she wrote for the Guardian titled “The Gift of Disease”: “Even now, it is strange to me. I have no idea why I am telling it. I have never been sentimental. Perhaps just to say that it happened.” Acker doesn’t know why she would link herself to her cancer and yet she still does: “In April of last year, I was diagnosed as having breast cancer.” Acker dies of it in 1997.

There is no disease more calamitous to women’s intellectual history than breast cancer: this is because there is no disease more distinctly calamitous to women. There is also no disease more voluminous in its agonies, agonies not only about the disease itself, but also about what is not written about it, or whether to write about it, or how. A disease suffered almost entirely by women presents the disordering question of form. The answer is competing redactions, and these redactions’ interpretations and corrections. For Lorde, the redaction is cancer’s and the silence around it is an opportunity: “My work is to inhabit the silences with which I have lived and fill them with myself until they have the sounds of brightest day and loudest thunder.” For Sontag the redaction is the personal. As she wrote in a note under prospective titles for what will become Illness as Metaphor: “To write only of oneself is to write of death.”

A fourth title Sontag proposed for her never-to-be-written piece was “Woman and Death.” She notes that “Women don’t die for each other. There is no ‘sororal’ death.” But Sontag was wrong: The sororal death is not women dying for each other, but women dying of being women. Queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, diagnosed with breast cancer in 1991, at the age of 41, wrote that at her diagnosis she thought “Shit, now I guess I really must be a woman.” Sedgwick dies of breast cancer in 2009.

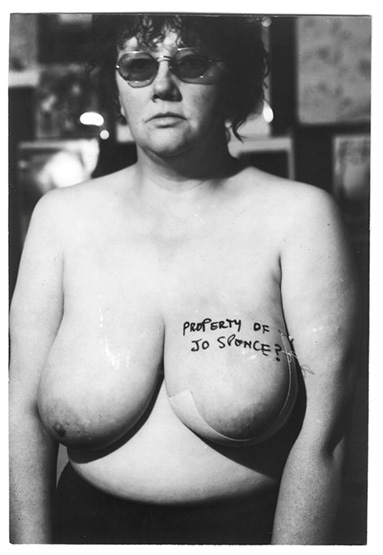

The sororal death is not without some sacrifice. At least in the age of “awareness,” that lucrative, pink-ribbon wrapped alternative to “cure,” women might not give up their lives for each other, but they do give up our breast cancer stories for the perceived common good. Reluctance to link one’s self to the disease, once typical of the silence around breast cancer, has been replaced with an obligation to always do so.

Though I might claim, like Acker, not to be sentimental, this sentence joins myself and my breast cancer in—if not a sentimental story—at least an ideological one:

“I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2014, at the age of 41.”

Breast cancer’s formal problem, then, is also political. An ideological story is always the story which, like Acker, I don’t know why I would tell but would tell regardless. And the sentence that begins the story—with its “I” and its “breast cancer”—joins “awareness” turned into perilous ubiquity. As S. Lochlann Jain writes in Malignant, ubiquity, not silence is now the greatest obstacle to finding a cure for breast cancer: “Cancer everywhereness now drops into a sludge of nowhereness.”

Most often only one class of people who have had breast cancer are regularly admitted to the pinkwashed landscape of awareness: those who have survived it. And to the victors go the narrative spoils. To tell the story of one’s own breast cancer is to tell a story of becoming a “survivor” via neoliberal self-management—the narrative is of the atomized individual done right, early-detected and mammogramed, of disease cured with compliance, 5Ks, organic green smoothies, and positive thought. As Ellen Leopold points out in A Darker Ribbon: “The external world is taken as a given, a backdrop against which the personal drama is played out.”

To write only of oneself, then, as Sontag suggested, might be to write not of death, but a type of death—or of a kind of death-like state to which no politics, no action, no larger history might be admitted. Breast cancer’s industrial etiology, its misogynist and racist medical history, capitalist medicine’s incredible machine of profit, and the unequal distribution by class of suffering and death are omitted from breast cancer’s now common narrative form. But to write of death is to write of everyone, or as Lorde wrote, “I carry tattooed upon my heart a list of names of women who did not survive, and there is a space left for one more, my own.”

In 1974, the year she was diagnosed with breast cancer, Sontag writes in her journal about a discovery made when thinking about her own death: “My way of thinking has up to now been both too abstract and too concrete. Too abstract: death. Too concrete: me.” She admits, then, what she calls a middle term: “both abstract and concrete” The term—positioned between oneself and one’s death, the abstract and concrete—is “women.” “And thereby,” added Sontag, “a whole new universe of death rose before my eyes.”