Anti-blackness and Islamophobia structure American Black Muslim subjects through opposing regimes of identity and visibility

There is a scene in Alex Haley’s miniseries Roots where Kunta Kinte, the enslaved protagonist, is in the hold of a cargo ship en route to the Americas. Having succumbed to nausea, he vomits on himself. Kunta is lying prone, squeezed into a tiny space packed with hundreds of other tortured Black bodies. Humiliated, he turns to a warrior from his village in Gambia who is chained alongside him on the roiling ship and shouts aloud that he is still a man – as though the words themselves made it true. The warrior turns to him and says, “Kunta, Allah sees. He understands; He knows you are a man.”

The first Muslims in America were Black. They were stolen from the western coast of Africa – modern-day Gambia, Nigeria, Senegal – and brought to the New World through violence. Some ten to fifteen percent of enslaved Africans brought to America as chattel practiced Islam as their faith when they landed on American shores. From the genesis of the American project, their labor – Black Muslim labor – would build the country from the ground up. But white Christian slaveowners did not tolerate these Africans practicing the religion they were born into. Enslaved Africans were converted to Christianity, wholesale, under threat of further violence. Like marriage, gatherings of Black people larger than three or four persons, or any other self-determined social custom, non-Christian religiosity was a threat to be eliminated amongst the enslaved. Black Muslim existence as Black resistance is as old as America itself.

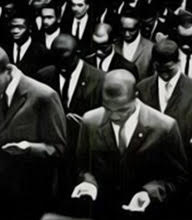

The Nation of Islam and other Black Muslim resistance movements that came out of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s might dominate our sense of its place in history, but Islam has been central to Black resistance and liberation movements for much longer than that. Muslim slaves and freedpeople in Georgia and South Carolina maintained their traditions at great risk to themselves in places like Sapelo Island and St. Simons Island – self-contained majority-Black enclaves with large, centralized plantation infrastructures. The first piece of Islamic jurisprudence written on U.S. soil was written some time in the 17th or even 16th century by an enslaved West African, likely from Guinea, named Bilali or Ben Ali Mohammet. Black Muslims existed prior to the colonial systems which brought them to the Americas, and they have been fighting assimilation for centuries. For a long time, to be Black has been to be Muslim. For many Americans, the two identities have been part of an active praxis of resistance that has been made hard to see in the archive of U.S. history. Much like in the central dogmas of more well-known and sometimes parallel Black Christian liberation movements, the Black American Muslim subject has always been whole in the eyes of her God.

In Roots, Kunta is warned of the dangers of practicing his faith by an elder named Fiddler: “You know white folks don’t like that kind of praying. You’ll make white folks mad and scared, nigga!”

The logic of white supremacy undergirding the horrors of slavery that Kunta Kinte's story illuminated in Roots was legitimized by the moral equivocation of a white Christian tradition which would create the savage/civilized binary. Christianity was used as a tool of racial control and a way to justify horrific injustices, and so Muslim slaves were not allowed to practice their faith precisely because slaveowners feared it serving as a locus for Black resistance. Despite this, the Christian faith tradition too was flipped by slaves into an ethos of resistance -- the Black church has been central to liberation movements, providing sanctuary and salvation to the enslaved and the oppressed in America for generations. But the brutal trappings of anti-blackness would remain.

* * *

“Ontology, the world’s semantic field, is sutured not simply by white supremacy. More specifically, it is held together by anti-black solidarity.” –Frank B. Wilderson III

Black Muslims fall into the rhetorical trap of anti-blackness as it exists today in what Columbia University professor Saidiya Hartman calls the “afterlife of slavery.” Her colleague Stephen Dillon explains that thanks to Hartman's analysis, “scholars have come to understand the barracoons, slave holds, and plantations of the Middle Passage as spatial, discursive, ontological, and economic analogues of modern punishment that have haunted their way into the present.” Folk rationalizations for anti-Blackness from above and below have survived along with these growths, sustaining cartoonish claims about Black people and Blackness that still structure our most quotidian choices as citizens.

Black people are (in no particular order):

lazy;

stupid;

untrustworthy;

deviant;

oversexed;

ugly;

violent;

rapacious;

brutal;

unfeeling;

inhuman.

Part of the covenant of the American Dream is an agreement non-Black immigrants enter into when they land on U.S. shores. It's an implicit contract with explicit aims: when you come to America, you'd better not ally yourself in any way with Black people or Blackness if you expect to get ahead. Black people are bad news. For Arabs and South Asians who make up a significant portion of the U.S. Muslim community, this manifests in a model-minority ethos that uses Black Americans as an example of what not to do and who not to affiliate with. I experienced this myself as a young Black Muslim woman, and it disgusted me. Ya abid! It was not uncommon to hear jokes whose punchline rested on a word that meant, essentially, nigger. When I resisted what I saw as racism from my Muslims peers, I would receive a half-hearted, “but we don't mean you! We mean those other Black people!”

My grandmother was a Black Somali woman who worked as law enforcement in the Emirates in the late 1970s. Widowed tragically young—my grandfather died in his forties—she was forced to take the position of breadwinner for her family, my young mother and her eight siblings. At the time, male police officers were not culturally permitted to deal with unmarried female subjects alone. Religious custom dictated the need for a small force of female officers, hijabis, who would process or interview women that the male police officers could not freely engage with. As a result, my mother and her siblings attended high school in Abu Dhabi, at an Arab school. My grandmother was and still is a hard woman. My mother and aunts and uncles, all nine of them, would learn Arabic and attempt to assimilate into Emirati life. But despite being an embodied representative of the state as a police officer, she suffered profound racism from Arab citizens.

My mother didn't talk freely about growing up in Abu Dhabi. As a child, I would pry for details sparingly given by her at long intervals. Because she would ritualistically remind me of the privilege I had growing up in the West, I wondered what her girlhood was like. I dreamed of my mother's adolescent becoming: Where did she go to high school? What was it like? How did she meet my father? These chapters were always missing, carefully excluded from the abridged version of her youth I got: the stories she would tell us of Somalia. Ha Nolaato! I was sure I came from a beautiful place in Africa where beaches were endless and guavas and papayas grew bigger than my head. What's more, Hooyo inscribed “Black is beautiful” on my brain when I was still small. Her standards of beauty and self were determinedly Afrocentric, something I would later learn was an act of resistance in her childrearing. But my mother would always tell me I was a Muslimah too, something I tried to incorporate into the way carried myself—even as a little girl.

It wasn't until I was out in the world myself—in the House of God of all places—that I would understand and experience anti-Blackness for the first time. At twelve, my tearful recounting of racism from my Brown Muslim peers at the kitchen table prompted my mother to finally open up to me about her own experiences in the Emirates growing up. They were ugly: her peers bullied her and her siblings systematically and on racial grounds. “Abid” was a word painfully familiar to her – but not one she expected to follow her through space and time, across the sea to the West. Here, where we would start over from the smoldering trauma the Somali Civil War left in its wake, we were still just niggers. Even to those we shared our deen with. My mother was heartbroken that she could not protect me from cruelties of those she saw as her own people, but chose to teach me to love Blackness and love Allah nonetheless. In her eyes and in His, I was whole.

* * *

As Black folks, we are in practice not a part of the larger community of Muslims; we are allowed to practice, but we don't share deen with the ummah. America is home to the most racially diverse group of Muslims in the world, but the community is still segregated. What does it mean to be seen as Muslim? As a legitimate believer? Whatever the answer, in the eyes of many U.S. Muslims today, it's negated by Blackness. Black Muslims are a contradiction in terms—invisible despite being the foundation for the faith in the country. Black Muslims are not seen as true Muslims. And that is the moral equivocation that legitimizes and props up all manner of anti-Black racism in American Muslim community today. Black people are not seen as viable potential partners in Muslim faith or love; Black families are not accepted into Muslim faith communities outside of their own. State violence against Black Muslims is not acknowledged or used to mobilize movements the way violence against non-Black Muslims does. One has to ask: does Black Life Matter to the Muslim community? Is the Muslim community aware of the structural impacts of anti-Black racism in America? The very idea of a larger coherent Muslim community is thrown into question when we confront cultural rifts as deep, wide, and painful as these.

The public perception of Muslims, particularly since the faith was thrust into the spotlight post 9/11, remains riddled with misconceptions. Racist stereotypes external to the Muslim community dictate that Americans still think of Muslims as brown bearded men. As recently as the white supremacist massacre at a Sikh gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, the conflation of Sikh men who wear turbans with Muslims has had deadly consequences. In 2013, Columbia Professor Prabhjot Singh, who studied hate crimes against Sikhs wrongly believed to be Muslim in the U.S. post-9/11, was himself the target for such violence. He was attacked by a group of young men on his way home in what was believed to be a hate crime. “I heard, ‘Terrorist, Osama, get him,’” Singh recalled, explaining in a New York Times article after the attack that “Our turban and beard are a trigger for fear in the minds of many Americans.” Public perception of Muslims as the bearded brown other post-9/11 functions as a shadowy parallel to Islamophobic state violence, the vigilante enforcer of racial categories of difference. Islamophobia is a lived reality for everyone who is Muslim, including those who are seen as Muslim but are not.

Because Black Muslims are not perceived as Muslim, they face rogue Islamophobic violence less often—but when that violence comes, their deaths do not garner as much outrage or mobilize Muslims in the same ways. Around the same time three young Arab Muslims were murdered in their Chapel Hill home, a Somali Muslim man was shot through the door of his apartment in Fort McMurray, Alberta. While Deah, Yusor, and Razan’s deaths trended worldwide, Mustafa Mattan’s murder was barely a passing blip outside of the Somali community. In a thought-provoking article co-written by UCLA Professor Khaled Beydoun and Muslim Anti-Racist Collaborative cofounder Margari Hill entitled “The Color of Muslim Mourning,” the authors pointedly ask the Muslim community who they prioritize and why. “Deah's fundraiser for dental supplies for Syrian refugees went from $20,000 before his death to $380,000. In contrast, Mattan's family still is struggling to raise $15,000 for his burial costs,” they write. The reality for today's Black Muslims is bifurcated into a war fought on two fronts: a battle with one's own community to be seen and respected as well as a battle to resist targeted state and vigilante violence. Black Muslims are also being surveilled, detained, and harassed by state operatives with increasingly alarming regularity. As Muslims, and as politically concerned citizens, we know the name of someone like Omar Khadr. How many of us can say the same of Mahdi Hashi, a Somali British national who has been stripped of citizenship and currently rots away in detention in Manhattan after refusing to spy on other Muslims? The Muslim community’s disinterest in his case speaks to the violence of what Frank B. Wilderson has termed “anti-Black solidarity.” Even when protecting his community, Hashi remains invisible.

At the turn of the 20th century, Du Bois mapped a conceptual understanding of the Black American subject: “One ever feels his twoness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Double consciousness signifies a subjecthood, a self whose several identities are at odds with one another. To be Black and Muslim in America today is to live a sort of Du Boisian double consciousness with an added dimension of dissonant interiority. To be Black and Muslim is to occupy a space of simultaneous invisibility and hypervisibility. Blackness is hypervisible, perceived and consumed through the historical aperture of the brutality of slavery. The stereotypes about Black people that guide our most quotidian and unconscious choices dictate that Blackness is dangerous: something to be contained; a threat. Blackness does not ask the Black subject to legitimize their Blackness, perhaps as a consequence of hypervisibility. It is simply a fact of one’s being, a physicality that signifies much more than just melanin.

But when you add the identity marker of "Muslim" to that of "Black," something very different happens: erasure. Black Muslims are invisible to their faith communities and to wider society, for Muslims, unlike Black people, must actively legitimize their identities as Muslims—through practicing faith, maintaining proximity to a community, or a cultural inheritance. The hypervisibility of Blackness makes one’s identity as a Muslim impossible precisely because Blackness precludes Muslimness in the cultural imaginary. So to occupy both subject positions is to experience the downward thrust of cognitive dissonance: you will always be too Black to be a true Muslim, but you must live with all of the pain that America inflicts on both Black people and Muslims. How are we to understand ourselves and our social locations, if being Muslim precludes being Black, which cannot be reconciled with being an American subject? The historical and contemporary erasure of Black Muslims can only be situated in the context of a violent anti-Black solidarity; the Black Muslim in America must then contend with an economy of unresolved strivings—towards faith, visibility, resistance, and self determination.