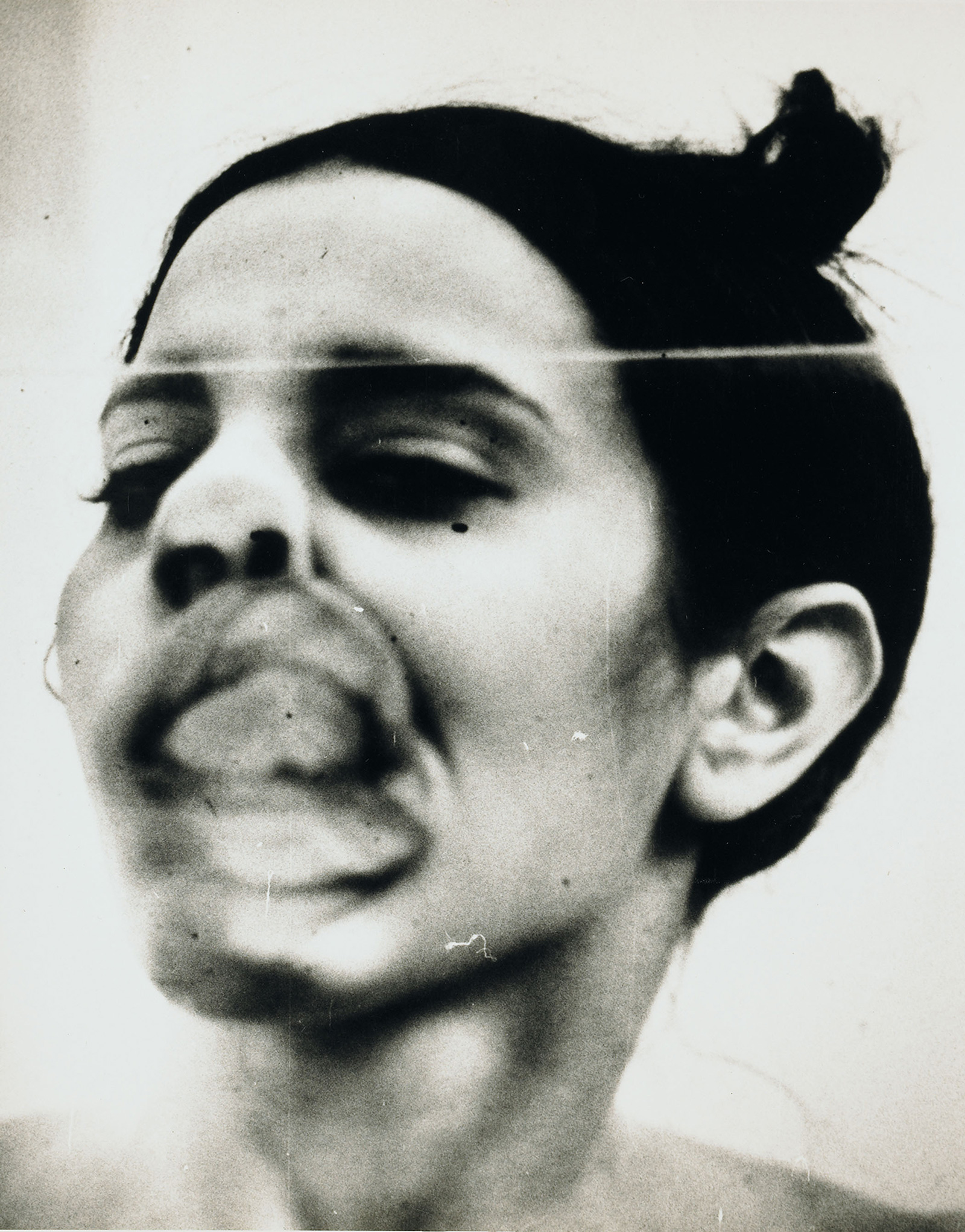

How artist Ana Mendieta is unremembered

In 1992, protesters stood outside the opening of the short-lived Guggenheim Museum Soho location with banners, asking, “Where is Ana Mendieta?” No one was looking for an answer—everyone knew where Ana Mendieta was. In September 1985, she died after falling out her apartment window under what can only be referred to as suspicious circumstances. Her husband, heralded artist Carl Andre, was tried and ultimately acquitted of murder, earning him a new sobriquet: “The O.J. of the Art World.” Since then, a significant amount of writing about Mendieta has focused solely on her death, and indeed, as someone who has only ever known Mendieta as deceased, I understand the impulse. The eerie circumstances—a fall after a lifelong fear of heights, her body left un-photographed by police after a career of photographing her own body—as well as the infuriatingly unresolved cause of death creates a compellingly dramatic and structurally tidy narrative.

Protesters asked, “Where is Ana Mendieta?” to remind that Ana was a physical presence on this earth. But asking “where” also implies that Ana Mendieta is a force that can be contained. Over the course of her career, Mendieta created almost 80 films, making her a more prolific filmmaker than Mary Kelly, Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman, Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, Dennis Oppenheim, or Nancy Holt, just to name a few of her contemporaries, despite not really being a filmmaker. She staged performances but was not a performance artist. She worked with the earth but was not an earth artist. She resisted the label of “feminist artist” after finding the movement too white and exclusionary; she felt exiled from Cuba, but made homes in the U.S. and Rome. She created works that invoked specific goddesses and magic but resisted being included with the essentialist “feminist goddess” works of the 1970s, like Judy Chicago’s Fertile Goddess plate in The Dinner Party or Mary Beth Edelson’s Woman Rising/Spirit. There was no label large enough for all the art that Mendieta made. That is, until she died, and there was one label for what she was: gone.

Jane Blocker, author of Where Is Ana Mendieta? Identity, Performativity, and Exile, cautioned against a quest to pin Ana down in an exact place. “The urge to locate Mendieta dangerously assumes that securing a place in the history of art necessarily translates into increased power, an assumption to which many women and artists of color have fallen victim.” Being an easily categorized artist on a popular index is not real power; the power always lies with the person making the index.

A different question is asked by Christine Redfern, author, with illustrator Caro Caron, of the graphic novel Who Is Ana Mendieta? I asked her about the book, and she told me she wrote it in part “to draw attention to the fact that who is remembered is a subjective, not qualitative, decision. We are all complicit in the writing and retelling of history.”

Redfern pointed me to “The Materialist,” a profile of Carl Andre by Calvin Tomkins published by the New Yorker in December 2011, where this line appears: “It is hard to think of an artist whose career has been so negatively affected by circumstances that have nothing to do with his art.” “I can think of one artist whose career was more negatively affected by the very same set of circumstances,” says Redfern. “Ana Mendieta.”

Writings about Ana are often deeply felt, beautiful, moving, reading like letters to a forever-lost lover. But if every letter is a love letter, every essay becomes a eulogy, and Mendieta moves further away from our mortal realm. I don’t think her death is the end of her story. There’s a problem with the tidy, compelling narratives about Ana Mendieta: She’s not missing after all. And I’m taking the train to find her.

***

Nearly every day, I walk by the Art Gallery of Ontario, but I haven’t bothered to see its current exhibit, a show on loan from the Guggenheim Collection about “masterpieces” that “changed things forever,” made mostly by white European men. But 10 minutes after discovering there was an Ana Mendieta exhibition at a gallery in Ottawa, I bought a ticket for a four-hour train ride to go see it.

Mendieta was born in Cuba in 1948. When Castro came to power, there were rumors that the children of wealthy families would be sent to a Marxist school in the Cuban countryside to try to cure them of their capitalist leanings. Ana’s parents sent her and her sister Raquel to the U.S. as part of a program sponsored by the holy trinity of shared interests: the American government, gas companies like Esso and Shell, and the Catholic Church. “Operation Pedro Pan,” as it was known, brought Cuban children first to Miami and then to an Iowa reform school. There Ana was mocked for her skin color and immigrant status; later she would speak about how those years influenced what she called her “earth-body-art”: “I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe.”

From 1970 to 1980, Mendieta studied and worked at the University of Iowa. In these prolific years she performed (Untitled) Rape Scene and Rape Performance in 1973, pieces inspired by the rape and murder of a student at her school. In these pieces, she invited friends and classmates to “find” her bound, bent over a table, blood smeared on her legs, with evidence of a crime strewn across her apartment. That same year, she would stage People Looking at Blood, Moffitt, in which she poured a blood-like substance in front of a local business with crumpled up rags left haphazardly on top, as though someone had abandoned cleaning a crime scene halfway through, and photographed the faces of passers-by until the store owner came and cleaned it up.

In The Art of Cruelty, Maggie Nelson describes seeing these two works at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art in 2007. For Nelson, neither piece can be categorized as a “look-at-how-bad-rape-and-murder-is feminist gesture.” “You can’t toss it into the ghetto of feminist protest art and ignore its more aggressive, borderline sadistic motivations and effects … Mendieta’s audacity was to claim this multivalence repeatedly and without apology, regardless of the culture’s capacity to apprehend it.” But Nelson notes the critical difference between the two: Rape Scene and Rape Performance have an explanation attached. People Looking at Blood only “intimates that a grievous and dramatic injury has taken place, but it gives no explanation, and more important, no recourse to action.” The people photographed walking by make it look as though they acted on and felt an “uncaring abandonment, even if of an indeterminate or imaginary entity.” The message reads as: What can we possibly be expected to do with this information?

Canadian artist Elise Rasmussen poses a similar question with two pieces related to Ana Mendieta, which I saw at Gallery 101 in Ottawa and which will appear in New York in May 2014. The first, Variations, is all about her death—a video recording of a workshop Rasmussen staged where two actors re-create the three different versions of Carl Andre’s story about the last night of Ana’s life: the 911 version, in which Carl told the operator that he and his wife were artists and that she had “somehow gone out the window,” the version he told the police, in which they were fighting about Carl being a more successful artist and he said that maybe in that way he was “responsible for her death,” and the version he told Calvin Tomkins, stating that Ana was cold and drunk and fell out the bedroom window trying to close it. Each version has the same ending.

But Variations doesn’t just film the actors. Instead, Rasmussen films the entire experience, showing the walls of the set and the audience watching intently. She interjects with facts where appropriate—noting the temperature on the night Ana died to counter Andre’s defense attorneys’ claim that she was cold and mentioning Ana’s well-documented phobia of heights. The audience poses questions to the actors as if they are really their characters: They ask Ana why she didn’t just leave and wonder if Ana’s drinking could have impaired her motor skills enough to make opening a window difficult. The actors pause to question whether their staged fights have enough intensity. Even with the constant breaking of the fourth wall, though, Variations is disturbing to watch. I can see that the window Ana will fall through is perhaps only two feet above the stage—but I still flinch every time the scene ends with Ana on her way out.

Variations is upsetting precisely because of its exposed artifice. If Andre, as the only witness to Ana’s final moments, can continue to change his story of what happened that night, then we should be able to do the same, Rasmussen seems to be saying. As viewers and admirers of Mendieta’s work and life, don’t we have a right to our own versions?

The death of Ana Mendieta was a tragedy. But the legacy of her death, violent and mysterious, is a true travesty. With her death, Ana is relegated to the multiple unexplained acts of violence seen around the world, just another number on a statistics sheet; or, worse, she’s fodder for the ripped-from-the-headlines school of crime fiction, the “based on a true story” effect, designed to produce an artificial chill at the gory descriptions of what might have happened. Ana dies and dies and dies every time her story is mentioned, but her life, the incredibly strong, clear, focused, ambitious life she lived, becomes a footnote.

Rasmussen has been working on her Mendieta projects for the past two years, after reading Naked by the Window, Robert Katz’s book about Andre’s trial, in conjunction with the New Yorker profile and seeing for herself how his story had changed. Since then, she has traveled to many of the places that were important to Mendieta in Rome, Mexico, and Cuba. Though the Guggenheim Museum and the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba both told her that Ana’s Rupestrian Sculptures had disintegrated back into the earth—a normal occurrence for works that were always meant to point to the ephemeral nature of landscape—Rasmussen decided to visit the sites to see for herself where Ana had worked and found the Sculptures, largely intact, exactly where Ana had left them.

Mendieta worked deliberately to avoid having boundaries placed on her and her work. The negative aspects of this are clear. Without an object to commodify, works like Rupestrian Sculptures are labeled so inconsequential that the Guggenheim considers them nonexistent. Yet almost 30 years after her death, the lack of boundaries around Mendieta’s work gives us the chance to continually discover her. She herself liked the idea of leaving works to be found out of context, without any explanations given, no telltale plaque providing exposition behind a velvet rope. Olga Viso, in Unseen Mendieta, notes that “Mendieta became increasingly interested in the residue that frequently remained in the landscape when works were completed. She liked to think that someone hiking in the area might discover one of her weathered Siluetas and believe that they had stumbled upon a prehistoric gravesite, carving, or painting.”

We know where Ana Mendieta physically is, if not spiritually. But her presence as an artist must be maintained and given priority over her death if we, the people still looking for her, want to keep Ana Mendieta present and not a gradually disintegrating idea like a sculpture she left in nature, already presumed to be gone. “Finding the sculptures has caused a bit of a conflict for me with regards to research and what is reported about her and her work,” Rasmussen tells me. “It causes me to question the importance that major institutions place on her as an artist, while at the same time it makes me realize the importance of actually experiencing something firsthand and not taking the authoritative word as doctrine.”

Rasmussen’s second Mendieta-related work, Finding Ana, is a series of color photographs she took to document the current state of the Rupestrian Sculptures. She brought back a small, pale stone from First Woman, which sits in a glass box next to a book turned to a page with the original black-and-white photograph of the work. “Ana meant for the work to exist through her documentation. Her work was ephemeral and I believe she enjoyed the idea of it returning to the earth. So finding the sculptures didn’t mean I necessarily found the work, as the work lives on through the images. For me it was much more personal, of being able to actually touch and feel the same limestone that she carved. In a way it brought me as close to her physically as possible.”

In And Eve Said to the Serpent, Rebecca Solnit discusses the violent nature of the Garden of Eden. A paradise with walls shouldn’t really be considered a paradise, but then, all our Western cultural values define a paradise as a “pure” place, free from “contamination.” A paradise with walls increases the value. A paradise with walls implies that there’s something privileged, rare, that has to be earned before entry.

Of course, it also implies a chance of having your entry revoked. “Paradise means a walled garden, and when Adam and Eve are expelled from Eden, its walls first appear in the narrative, because they only matter from the outside,” Solnit says, before she dryly remarks that “Adam and Eve are the first refugees, the fig leaves the first canceled passports, paradise the first immigration-restricted country.”

The experience of being exiled from Cuba left Mendieta permanently questioning those intangible walls most of us take for granted: a home versus a shelter, belonging versus traveling. While she spoke about wanting her art to tie her back to the universe, it was never as simple as returning to where she was born. Solnit rightly points out that the version of Genesis we know now is a politically motivated retelling of what the original might be, that the willful woman and deceptive serpent are just myths designed to keep devotees docile. The Cuba of her youth was not a paradise Mendieta had been expelled from; likewise, the art she made was not so pure it required sanctuary in clean galleries with ticket prices at the door.

Mendieta wrote about freedom from exile in a project for the feminist art journal Heresies, a collage of text and images about a Cuban legend: the “Black Venus,” a woman who passively resisted being captured and enslaved by Spaniards. She was, in Ana’s retelling, so beautiful “that the most demanding artist would have considered her an example of perfect feminine beauty.” The Black Venus lived alone, except for a white dove and blue heron that followed her everywhere, and was mute. The Spaniards tried to “civilize” her but she withdrew, stopped eating, stopped responding, until they finally let her return to her home. “Today the Black Venus has become a legendary symbol against slavery,” Ana concluded, “She represents the affirmation of a free and natural being who refuses to be colonized.”

I had a lot of time to think about borders and boundaries, passports and permissions, on the train. The question why—why I, on a moment’s notice, spent four hours each way just to ultimately spend an hour looking at Rasmussen’s work—kept echoing in my head. What was physically present there that I couldn’t get by staying where I was?

I don’t often visit art galleries, and when I do, I am a bad visitor. I rush. I feel like I’m being watched as I look, being judged as I hesitantly judge. I’m convinced it’s all over my face; I don’t belong there. I am constantly imagining people watching me. Like any good former art-history student, I know my John Berger.

But there’s something about Ana Mendieta’s work that inspires an urge to flee, travel, to go toward it instead of waiting for it to come to you. For Rasmussen, being told that Rupestrian Sculptures were gone didn’t stop her from flying to Cuba. Like a character from mythology, she was rewarded for her diligence.

Ana Mendieta is not a gravesite for someone to stumble on, even if her remaining siluetas now serve that purpose. In March 2014, Rizzoli will publish She Got Love, the catalogue from the exhibition of the same name at the Castello di Rivoli in Italy. Mendieta’s estate is carefully managed by the Galerie Lelong, and as more artists like Elise Rasmussen and Christine Redfern continue to talk about Ana Mendieta, her life will never be colonized or exiled outside of paradise’s walls. The question is not “Where is Ana Mendieta?” The question is, “Where will Ana Mendieta take you?”