You’re a good cop, but a loose cannon. Give me your badge and gun.

Most Americans could write this scene and probably fill in the rest of the narrative while they’re at it. It takes place in the police chief’s office; he’s the one addressing a rogue cop. The cop is a good cop, he is courageous and resourceful with strong instincts and boundless determination. But the good cop has a problem—the letter of the law, the bureaucracy with its endemic corruption, the miles of red tape—all prevent him from doing his job. In striving to uphold the law, he stumbles over the threshold to the wrong side. The good cop is also a bad cop.

This is the classic antihero and his dilemma as it has played out in movies likeDeath Wish and Dirty Harry: Is he justified in using disorderly means to achieve orderly ends when orderly means are unavailable? Movies and TV shows have recycled this archetypal conflict so often that it belongs in the pantheon along with “I scheduled two dates for one night!” and “I’m supposed to marry rich guy, but I love poor guy.” As audiences got knowing and jaded, the scripts evolved. Cannons got looser and steps over the line went further and became more deliberate. In the past few years, we’ve seen a series of TV shows in which upping the antihero has crossed its own line, and the old questions about means and ends have ceased to apply. The old cop who chafed at institutional limits has undergone a neoliberal transformation: The result is a new kind of series that we might call the consultant procedural. A derivative of the cop and private investigator procedurals, the consultant procedural starts with some sort of institutional disqualification and follows the central character as he or she ports unmatched professional skills from job to job.

This shift from career-officer protagonists to mercenary contractors is so prevalent that the USA network has built its current identity out of it: Psych, Monk, Burn Notice, and White Collar all straddle the same public-private line between officially sanctioned law enforcement and guns for hire. The pattern has even spread to the “hot doctor” subgenre (“You’re a good surgeon, but a loose cannon. Hand in your scalpel.” ) with Royal Pains. And it’s not just USA, other networks’ recent shows, like The Mentalist, Bones, Lie to Me, Numb3rs, or even the BBC’sSherlock Holmes miniseries, use the stability of public institutions to provide a consistent narrative base for exciting episodes that take place in the private sector. The new clichéd antihero can work with the government, but he or she must be entrepreneurial above all.

All these shows draw their narrative energy from the constant search for work. Instead of having cases coming to them in an oppressive deluge, as in the Law and Order franchise and other traditional cop procedurals, these protagonists must scrape for work wherever they can find it. This puts them in direct contact with the eccentric moneyed class – whether drug kingpins or TV stars. Rapid case turnover and constant semi-employment provide the structure for the consultant procedural, giving writers a good justification for open-and-shut, single-episode stories.

The genre hasn’t arisen by coincidence. Book reviewers at the Los Angeles Times,recently fired and hired back as freelancers, can empathize with Burn Notice’s Michael Westen, who risked his life for seasons to reveal a conspiracy and reclaim his CIA job, only to be taken back as a consultant in the latest season. It’s no surprise that television writing can reflect — or even predict — changes in American labor.

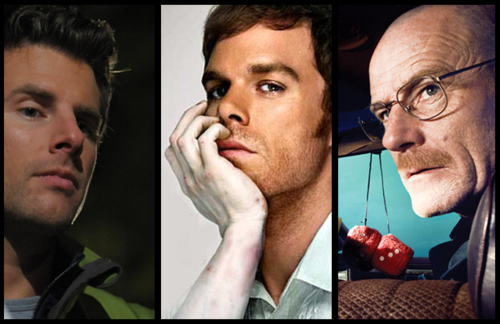

Although there are other examples, I’m going to focus on three shows that stretch the definition of the consultant procedural: Breaking Bad, Dexter, and Psych. The three differ widely in tone and content, but their protagonists all trace their lineage back to the rogue cop cum independent consultant. Of the three, Breaking Bad is influenced most by the old antihero’s moral transformation, with cancer-diagnosed, public-high-school chemistry teacher Walter White (Bryan Cranston) taking a second job as a meth cook for hire – a quality consultant. Dexter’s titular character (Michael C. Hall), a crime-scene analyst with an uncontrollable urge to murder, is a serial killer who generally limits himself to other serial killers. His co-workers don’t know where he gets his insights, but Dexter is a murder consultant, using experience from his nocturnal profession to inform his day job.Psych, as the only real comedy on the list, may seem an odd entry, but the underachieving cop’s son (James Roday as redundantly fake psychic Shawn Spencer) conning his way into a job as a police consultant using phony powers is a self-aware version of this same story. Police consultant is the perfect job for a cop who doesn’t want to play by a cop’s rules.

As with the archetypal antihero of old, the audience doesn’t want to see any of these protagonists caught or returned to stable work, not only because they’re likable, but also because it would likely involve some shark jumping. But unlike the traditional antiheroes, whose drama hinges on whether they will cross the line and use unlawful means, the protagonists in my examples have each forsaken ethical means from the beginning and hardly look back. Dexter accepts that he’s a murderer; whether or not it’s okay to cut up serial killers isn’t really a valid question for him. Psych’s Shawn doesn’t trouble himself much over his fraud or flouting of police procedure and regulations.

Instead of the traditional ends-means conflict, the motives question becomes central in consultant procedurals. Is Breaking Bad’s Walter really cooking because he wants to help his family or because it finally allows him to get the respect he deserves? Is Shawn working with the police because he cares about people, or is it another adolescent prank designed to get him attention and an adrenaline fix? The difference between Dexter’s acceptable and unacceptable kills isn’t in what he does, but why he does it.

Traditionally, this sort of motive question has belonged to the villain. The villain, after all, often justifies himself with twisted reasoning, which, the hero is usually left to point out, is only a cover for greed or the lust for power. But with the consultant procedural, the antihero arms race has displaced the hero altogether and left an anti-villain, a bad guy with a good motive.

But the old-style antihero isn’t absent from the consultant procedural; he has just been reduced to a supporting role. Breaking Bad, Dexter, and Psych all have secondary cops with means-ends conflicts. In Breaking Bad, it’s Hank (Dean Norris), the brother-in-law who is (in)conveniently a DEA agent. A jocular boor who rejects promotion to remain comfortable in his familiar Albuquerque office rather than serve on the regional front line in El Paso, Hank is a skilled cop who gets closer than any other character to catching Walter. As the only DEA agent who seems to appreciate the significance of the premium meth Walter makes, Hank pushes himself over the line and beats up Walter’s hapless partner Jesse (Aaron Paul). Shamefaced but honorable, Hank plans to plead guilty and resign from the agency before Walter intervenes behind the scenes to have the charges dropped.

Like Hank, Psych’s veteran detective, Carlton Lassiter (Timothy Omundson), can’t hack it in the big leagues. In keeping with Psych’s ADD po-mo charm, he’s not so much a movie antihero cop as a cop who models himself on movie antihero cops. But amid Shawn and his partner Gus’s (Dulé Hill) buddy-comedy hijinks, the show never develops “Lassie” and his conflicts with his partner Juliet (Maggie Lawson) – young, female, gorgeous – and Police Chief Vick (Kirsten Nelson). The series hints at a wrecked marriage and his obsessive need to be the cop archetype he imagines he should be (setting him up for a means-ends crisis), but the writers never give him the narrative space to do much more than hint. Omundson imbues this straight-man role with occasional glimpses of stern sadness that make him a bright point in an already strong cast. In one episode, a visiting Fed tells him he could have been an FBI agent, maybe, if he’d gone to college. In another, he finds out that his score on the detective’s exam – which he believed to be the highest in the department – wasn’t only worse than Juliet’s, but also worse than Shawn’s, who aced the test as an adolescent. Lassiter’s good never seems good enough.

Only one of these shows has sacrificed its antihero to a season finale, and Dexterhas never fully recovered. In the first season, only one character is on to the titular killer. Bristly Police Sergeant James Doakes (Erik King) keeps Dexter up at night, but his single-minded dedication to the job makes him unpopular around the office when compared with Dexter, the genial psychopath. Doakes sees through his co-worker’s managed exterior, and his cop’s instincts pay off when Dexter gets careless. He’s able to solve the case, but since others won’t be convinced, Doakes goes off the rails alone and crosses the line. Unfortunately, Dexter is waiting on the other side, where he sets him up to die and take the posthumous blame for the killings. In each case, if the secondary antihero can’t accept the liberties consultants must take, then his days are limited.

The central moral question has shifted with the central moral actor. All these characters have to yield to the anti-villain, whether in death, paralysis, or quiet desperation. As a central figure, the antihero is used up, but next to the consultant anti-villain, he gains a critical edge. If employees are now supposed to put their personalities to work, what happens to the cops who are “all about the job?” InBreaking Bad, Hank finds out quickly that not knowing Spanish—a language he thought belonged to the enemy— will hamper his chances to move up in the DEA. He’s not a model of nativist anger but of the role confusion that comes with changing standards. Lassiter’s job (and professional conflicts) have been outsourced to plucky mercenaries wielding supernatural powers – how is he supposed to compete with that? And what use is a loose-cannon cop when there’s a perfectly effective serial killer doing his job for him? The good cop was always insufficient, as if questions of obedience and the social contract were only trying if experienced by real citizens. Counterintuitively, it’s the shift toward precarious work that makes the antihero’s role compelling once more. Confronted with consultants who aren’t troubled by the same means-ends line, the tough cop finds himself struggling without stakes. He realizes what was true all along—justice and injustice have very little to do with his individual choices, no matter how agonized.

The villainous turn makes sense in an America where the career public servant is no longer the representative worker. Instead we have the precariat – loosely attached workers cobbling their livings together from broken parts inside and outside the state and law. Consultants Shawn and Gus jump back and forth from public to private clients, operating in the neoliberal gray zone of private government workers. Walter is a schoolteacher who at first has to work an after-school job at a car wash where he’s mocked by his wealthy students. That is, until he entrepreneurially repurposes district chemistry equipment to cook meth. Dexter doesn’t obsessively take his work home like the antihero cops of yore; instead, he spends his taxpayer-funded hours plotting his vigilante escapades, his job no more than a useful cover. All three of these villains, and the new genre’s protagonists writ large, embody a fantasy of highly skilled American labor, justifiably “gone Galt” but still willing to do public work for the right price, somehow both forced and eager to leave old moral lines in the dust.