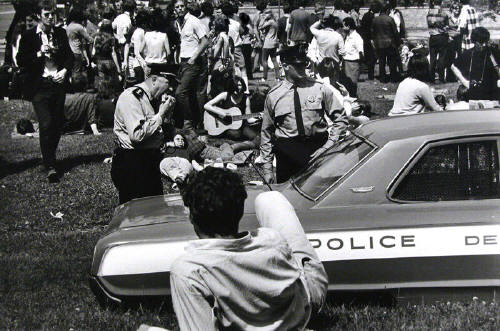

The debut march of the unlimited student strike on February 14 — initiated through general assemblies of fine arts students at the Université du Québec à Montreal (UQAM) and sociology grad students at Université Laval — wound through downtown Montreal and onto the McGill campus, there chanting “UQAM, McGill, même combat!” At a march through campus two months later, when demonstrators shouted “Wake up!” at McGill students lounging in front of the library, they yelled back, "No."

More than half of McGill undergrads are not from Québec, a fifth not from Canada, and we compose an international caste with prospects and a summer determinedly somewhere else. It’s no accident that Americans have pooled at McGill, unrooted, carpetbagger Americans, the most American of Americans in their flight from America. McGill markets and flatters these students, who pay $14,561 in tuition for a B.A. — an unambiguous clean trade between administrators of “Canada’s most international university” acclimated to more equitable Québec rates

By mid-March, 144,000 students across the province were en grève générale illimitée, and we didn’t really know what that meant at McGill, and now we were voting on it. Thousands of arts students queued for three hours to get into a rushed, two-hour general assembly, and those who stayed to vote left campus still not on strike but with its negation now embossed over all activity. McGill does not go on strike. An econ student had appealed in the debate period to his summer consulting internship, for which the semester had to end on time.

Here in June, the Québec student movement has had ascendant success in real cross-generational mobilization, led largely by francophone student associations and their emulators. The world’s lefty-intellectual eye is watching. The robust movement has never been solely against the tuition hike (increasingly, just an occasion for op-eds from near-sighted pragmatists) but has always pointed to something much larger. Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, co-spokesman of CLASSE, the most radical and prominent umbrella student association, concluded a speech back in October 2011,

The struggle against rising tuition fees, the struggle of the Occupy movement around the world, this struggle must be referred to by its name. This is a class struggle: a struggle between a possessing minority and a majority that owns nothing. A minority that sees life as nothing but a business opportunity, a tree as nothing but raw material, and a child as a future employee. And when we fight the tuition hike, let’s not forget that this is also what we are fighting. And so I wholeheartedly and gladly invite you to join us in the streets. Thank you very much.

His envoi “merci beaucoup” is a demure mumble that makes the 1917 rhetoric palatable, more real, just that easy, and participating in the world-historical dialectic becomes like RSVP’ing a dinner invitation. It’s important to note that this is all in French — such a speech wasn’t translated into English and rendered into one of those kinetic Web 2.0 typographic videos until April.

My emphasis here on McGill — totally irresponsible in a holistic account of the strike — is because I’m back in New York, relatively static, searching-for-bellwether New York. And McGill, the neoliberal American university by proxy, the phantom Canadian girlfriend of the Ivies, did significantly go on strike, at last, for a week, in a few departments, when bros from Connecticut found their Billy Budd lecture blocked by someone else’s history.

***

It was particularly pressing for the strike to hit the week of March 22, a massive demo timed for the release of the provincial budget, in which the government would underscore their recalcitrance on the hike. The failure of the March 13 strike vote in McGill’s Faculty of Arts was markedly sad as it confirmed a long McGill tradition of abstention from the Québec student strikes of '68, '74, '78, '86, '88, '90, '96, and ‘05. A top McGill student representative from 1978 termed that strike “unrealistic” and pejoratively, “Marxist.” This year, Arts students voted 609 to 495 not to strike as a faculty, in a majority noticeably made up of political science and economics students, with all the radicals back in Fassbinder seminars or reading Bourdieu, now feeling like shit.

So McGill activists then moved to organize more incisive and proximate departmental strikes, booking rooms for two weeks of unprecedented departmental general assemblies for social work, French literature, sociology, women’s studies, geography, art history, philosophy and English. All these departments voted to strike for different lengths, from general unlimited (with mandatory renewal each week) to one-day spurts, but the largest and most disruptive was the Department of English Students’ Association’s general unlimited strike of 1,200 students. English was the third department to vote: an auditorium was booked for March 19, a quorum was set for 75 English students (a relatively gratuitous 7 percent representation compared with the Arts Undergraduate Society’s benchmark 1.8 percent), and the strike motion passed 53-27, forming a strike committee that met immediately after the vote to plan pickets for the following morning.

The next day, an English student from Rumson, New Jersey, say, wakes up in an Aylmer greystone, walks two blocks to campus, past a picket at Wilson Hall, past the Arts Building steps draped in a banner in French, what else, that says McGill littérature française en grève, 4/5 cognately comprehensible, and then up the hill to the Education Building, where he finds the door to ENGL 360: Literary Criticism blocked by two ectomorphic arms that lead to red squares pinned to their breast. Say the Lit Crit prof has integrity and refuses to call security. He encourages his drowsy students, among them the Central Jerseyan, to honor the strike, but he must insist on his own entrance. The picketers refuse, the professor is frustrated and resigns (he was sympathetic anyway): class is cancelled. For our Central Jerseyan, this is weird, the closest analogue found only in fire drills, the word “strike” pulled from the Gilded Age chapter of a history textbook or his peripheral vision on a city street. He takes a more convenient, early lunch at an on-campus Subway outlet and arrives early to his next class in Arts 130:

Never has so much violence been wrought in ENGL 329: The Nineteenth Century English Novel. Our Central Jerseysan sits in the back, percussively annoyed, and watches his professor dumbstruck against the blackboard. A student shouts over the drums, “This is not a strike, guys.” But the strain in her voice betrays that a strike is exactly what this is: student strikes are tough, painful, intimate things, where “colleagues” and “classmates” and other nouns that follow “fellow” are now banging on industrial pails and calling you a fucking scab. You can feel shame and anxiety punish both protester and scab here as a vote tally becomes a face by face scan — count how many scabs bite their fingers, heads swiveling from prof to protestor, but then see how the drummers only eye the ground or each other, or run themselves into the corner or back into the hall. The one exception is the protestor in blue, co-author of the English strike motion, lording over his creation in a gaze that still terrifies me today in its poise and singularity of purpose — not smug, not severe, but sure. We’ve gone looking for that feeling everywhere. A central Jerseyan scab might begin to doubt himself.

This is the kind of thing that the department chair, scholar of Bowen and Compton-Burnett, would later tell me is trauma. I said, trauma, like 9/11, PTSD, long-term-ontological-damage-trauma. Not 9/11, but yes, he would be feeling this for a long time. The majority of professors were against the whole enterprise. Many thought, speciously, that the tuition hikes would bring greater funding to a cash-strapped humanities department, and accordingly, that undergraduates were shooting themselves, through their professors, in the foot. That Brechtian lecturing A Raisin in the Sun, that cineaste concerned with authorship & interpretation, that pervy Canadian poetry guy interested in “the beautifully warped minds of criminals, eccentrics, hangmen”—they all resented their radical students (whiny, fascistic, violent) once their syllabi became manuals. Faculty would later vote 13-8-2, in a closed meeting purportedly of shouting, crying, and Ciceronian prepared speeches, to formally censure their students for strike action.

The strike committee — which any English undergrad could attend — met later that Tuesday night in mild crisis and schism, prompted by an overflow of emotional emails from scabs and professors. The dominant sentiment was something like this:

If I had been in favour of the strike to begin with, I'm fairly certain this experience would have changed my opinion on the spot. Do not act like children if you have any interest in negotiating like adults. I sincerely hope that this "tactic" will not be used again. It is incredibly ineffective and disrespectful. Before today you had in me a relatively ambivalent bystander, but if this kind of behaviour continues you will have another vehement opponent.

For the majority of us new to hard picketing, for whom that day was an introduction to an almost yearlong student protest and the entire Québécois history of student strikes, this was the type of person we felt we had to consider. We thought that beginning with hard pickets would turn “relatively ambivalent” students and professors against the strike. If we wanted the strike to be renewed next week, surgical escalation was necessary: hard on the patricians, soft-to-hard on sympathizers. We were English students after all, and PR, reception, interpretation seemed to matter. Others didn’t mind renewal and only wanted a weeklong blowout. Consensus became “firm” pickets: soft, but everyone had to actually show up and make it thick.

Jamie Burnett, a McGill activist, wrote that this is exactly what corrupted our strike:

An incredible amount of time and energy was wasted at McGill with the assumption that “McGill is different,” and that the methods of organizing which work everywhere else in Québec will not work at McGill. McGill is different, comparable with the most conservative of English Canada's universities. But the methods that worked everywhere else in Québec worked consistently at McGill where they were carefully and attentively tried … One common mistake at McGill was the holding of “soft pickets” where activists allowed classes to happen despite their strike mandate … People eventually come around, building a culture of solidarity and confrontational politics in the process.

Soft pickets certainly desiccated the strike—there is no collective shield for those students respecting the strike mandate when scabs go to class and do violence to transcripts that brandish unexcused absence after absence. At UQAM, hard pickets were applied to a school with maximal turnout at their strike vote and renewal assemblies, a norm of radical dissent and hard tactics, and the resonant legacy of the Quiet Revolution that has since bred nine significant student strikes in the past 44 years.

On Facebook events, flyers, and class discussions, the strike’s opponents would have to be given foreign history lessons that would only further estrange. They would be told why and what is a strike and why now, followed by empathic appeals to accessible education—a lexicon to be later adapted for their own self-interest in circumventing the strike and accessing their rightful classrooms. Blocking scabs at the door voided any chance of strike renewal, but talking policy or society also got nowhere, except now at the strikers’ disadvantage. Barring a significant majority and turnout at the initial strike vote, we should have just gone apeshit for a week for someone else’s movement and benefit, because we were lost.

Once pickets slackened into flyering and discussion, more skittish students like me joined the line, but the scabs only hated us after Tuesday and wouldn’t relent. The strike never ballooned, people didn’t come around. An activist cheered us for Thursday — the March 22 demo of 300,000 people across Québec — that it’ll feel good, it’s so different outside of here it’s incredible.

At the strike renewal assembly the next week, the scabs first came to gut the strike motion and then stayed to vote it down.

***

Once you could gather yourself, you’d realize this was a species of Hegel’s battle that rent political infinities on both sides and barked CHOOSE on the basis of everything you are. Students and professors felt physically sick, without sleep or calm — remember, in trauma — but others had adrenaline, satisfied at last to do what they were. Mind the intimacy of a strike in this small village of a department, and it’s unsurprising that we began to hate each other. Young people who look and sound like you, read the same books, live in the same Plateau, go to the same parties: you begin to trade links to the bad haircuts and indignant statuses of unambiguous scabs, those acquaintances from first year, those keyboard counter-activists who follow demos on the Montreal police’s Twitter alone at home, who hate you in turn for your hipster affinities, self-righteousness, your study of literature. Professors cannot look at you, nor you them: they see what they should be without the demands of careerism, and you see what you risk becoming, who has been teaching you these years, all pathetic mountebanks with bibliographies for epaulettes.

A similar polarization has struck after the admission of loi 78, but to very different effect: a draconian law seems to have bridged students with everyone else under the keywords community and hope and love. Back in April we watched Tout va bien, blocked banks and finished our theses. And in May there were barricades and pylon fires followed by moms banging pots and wobbly old men taking hands off strollers to clap. Every eight PM people went to their nearest major intersection and effectively RSVP’d that dinner invitation to the Weltgeist by thrumming silverware and redoubling into spontaneous several-thousand person marches. That familiar lefty-intellectual eye marvels at those spontaneous crowd tallies in Montreal’s streets, but such magnitude is possible largely because school’s been out since February, when the manif en cours displaced those MWF lectures.

The immediate ugliness of scab-shaming, or really just the peregrine ring of hearing yourself chant, is obscured à la Internet, with the drumstick’s dissent like an anonymous blog comment. A higher umbrella abstraction of “red square” aligns both a popular, family-friendly march in the early evening and economic disruption at night and the next morning’s rush hour. It’s panning out that being pollsters by day and terrible at night is pretty good strategy. One student union places the cost of the strike at $104,000 an hour due to teacher pay, city damages, and police overtime — a number that will only grow over the summer festival season. Students have no better leverage than when the hoteliers start to shout at tourism ministers and city mayors bleed city money for provincial budget plans. Kitchenware clamor may paralyze no trader, but a feel-good meme saves a lot of face for an anticapitalist Götterdämmerung.

Beside this crescendo, the semester has ended at McGill and its students have fallen un-, underemployed or left the province. You get the creeping sensation that it’s much, much better off without you and all your friends. Everything in Montreal now only says: see families in the streets, American tourist, and then write about how you blocked one of our banks in more of an economic border-war than a sickly Byron fighting for our belle province. You can write how the Banque Nationale complex downtown felt like a playground, the irony of how your uncle works in their securities department, all of your fun. Write what you should take from us. And now it’s impossible for me to discern where the national should end and international solidarity begin, when this parasitism slides into constructive borrowing. Are you adapting, emulating, or stealing, and does it matter? How should a tourist be? What do you responsibly take south? One familiar lesson presents itself and can only be written in English: we have hope now, but not for us.

The feeling on the ground there is still a conceit that sweeps up everyone — regardless of the range of their participation — in flat negation against austerity, state bullshit, contempt for others. During the day there, pedestrians scan for a pinned red square before clothes or face, for a shape wholly abstracted to accommodate its disparate contours: he flyers the post, she blocks the street, she finds a resonant beat in the pan, they pace the crosswalk like sentries, they talk excitedly about tonight, he writes them all into semi-lyrical essays. A McGill degree, bad French, a study visa, or grey hair seem no disqualification from something this good. It is summer, after many springs, and many clichés about spring, and a Montreal summer has not been more beautiful in memory.